Easter

Easter, History, Traditions

Piero della Francesca, Resurrection, circa 1463, Museo Civico, Sansepolcro

From Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, 1869:

Easter

Easter, the anniversary of our Lord’s resurrection from the dead, is one of the three great festivals of the Christian year,—the other two being Christmas and Whitsuntide. From the earliest period of Christianity down to the present day, it has always been celebrated by believers with the greatest joy, and accounted the Queen of Festivals. In primitive times it was usual for Christians to salute each other on the morning of this day by exclaiming, ‘Christ is risen;’ to which the person saluted replied, ‘Christ is risen indeed,’ or else, ‘And hath appeared unto Simon;’—a custom still retained in the Greek Church.

The common name of this festival in the East was the Paschal Feast, because kept at the same time as the Pascha, or Jewish passover, and in some measure succeeding to it. In the sixth of the Ancyran Canons it is called the Great Day. Our own name Easter is derived, as some suppose, from Eostre, the name of a Saxon deity, whose feast was celebrated every year in the spring, about the same time as the Christian festival—the name being retained when the character of the feast was changed; or, as others suppose, from Oster, which signifies rising. If the latter supposition be correct, Easter is in name, as well as reality, the feast of the resurrection.

Though there has never been any difference of opinion in the Christian church as to why Easter is kept, there has been a good deal as to when it ought to be kept. It is one of the moveable feasts; that is, it is not fixed to one particular day—like Christmas Day, e. g., which is always kept on the 25th of December—but moves backwards or forwards according as the full moon next after the vernal equinox falls nearer or further from the equinox. The rule given at the beginning of the Prayer-book to find Easter is this: ‘Easter-day is always the first Sunday after the full moon which happens upon or next after the twenty-first day of March; and if the full moon happens upon a Sunday, Easter-day is the Sunday after.’

The paschal controversy, which for a time divided Christendom, grew out of a diversity of custom. The churches of Asia Minor, among whom were many Judaizing Christians, kept their paschal feast on the same day as the Jews kept their passover; i. e., on the 14th of Nisan, the Jewish month corresponding to our March or April. But the churches of the West, remembering that our Lord’s resurrection took place on the Sunday, kept their festival on the Sunday following the 14th of Nisan. By this means they hoped not only to commemorate the resurrection on the day on which it actually occurred, but also to distinguish themselves more effectually from the Jews. For a time this difference was borne with mutual forbearance and charity. And when disputes began to arise, we find that Polycarp, the venerable bishop of Smyrna, when on a visit to Rome, took the opportunity of conferring with Anicetas, bishop of that city, upon the question. Polycarp pleaded the practice of St. Philip and St. John, with the latter of whom he had lived, conversed, and joined in its celebration; while Anicetas adduced the practice of St. Peter and St. Paul. Concession came from neither side, and so the matter dropped; but the two bishops continued in Christian friendship and concord. This was about A.D. 158.

Towards the end of the century, however, Victor, bishop of Rome, resolved on compelling the Eastern churches to conform to the Western practice, and wrote an imperious letter to the prelates of Asia, commanding them to keep the festival of Easter at the time observed by the Western churches. They very naturally resented such an interference, and declared their resolution to keep Easter at the time they had been accustomed to do. The dispute hence-forward gathered strength, and was the source of much bitterness during the next century. The East was divided from the West, and all who, after the example of the Asiatics, kept Easter-day on the 14th, whether that day were Sunday or not, were styled Qiccertodecimans by those who adopted the Roman custom.

One cause of this strife was the imperfection of the Jewish calendar. The ordinary year of the Jews consisted of 12 lunar months of 292 days each, or of 29 and 30 days alternately; that is, of 354 days. To make up the 11 days’ deficiency, they intercalated a thirteenth month of 30 days every third year. But even then they would be in advance of the true time without other intercalations; so that they often kept their passover before the vernal equinox. But the Western Christians considered the vernal equinox the commencement of the natural year, and objected to a mode of reckoning which might sometimes cause them to hold their paschal feast twice in one year and omit it altogether the next. To obviate this, the fifth of the apostolic canons decreed that, ’ If any bishop, priest, or deacon, celebrated the Holy Feast of Easter before the vernal equinox, as the Jews do, let him be deposed.’

At the beginning of the fourth century, matters had gone to such a length, that the Emperor Constantine thought it his duty to take steps to allay the controversy, and to insure uniformity of practice for the future. For this purpose, he got a canon passed in the great Ecumenical Council of Nice (A.D. 325), that everywhere the great feast of Easter should be observed upon one and the same day; and that not the day of the Jewish passover, but, as had been generally observed, upon the Sunday afterwards. And to prevent all future disputes as to the time, the following rules were also laid down:

-

‘That the twenty-first day of March shall be accounted the vernal equinox.’

‘That the full moon happening upon or next after the twenty-first of March, shall be taken for the full moon of Nisan.’

‘That the Lord’s-day next following that full moon be Easter-day.’

‘But if the full moon happen upon a Sunday, Easter-day shall be the Sunday after.’

As the Egyptians at that time excelled in astronomy, the Bishop of Alexandria was appointed to give notice of Easter-day to the Pope and other patriarchs. But it was evident that this arrangement could not last long; it was too inconvenient and liable to interruptions. The fathers of the next age began, therefore, to adopt the golden numbers of the Metonic cycle, and to place them in the calendar against those days in each month on which the new moons should fall during that year of the cycle. The Metonie cycle was a period of nineteen years. It had been observed by Meton, an Athenian philosopher, that the moon returns to have her changes on the same month and day of the month in the solar year after a lapse of nineteen years, and so, as it were, to run in a circle. He published his discovery at the Olympic Games, B.C. 433, and the cycle has ever since borne his name. The fathers hoped by this cycle to be able always to know the moon’s age; and as the vernal equinox was now fixed to the 21st of March, to find Easter for ever. But though the new moon really happened on the same day of the year after a space of nineteen years as it did before, it fell an hour earlier on that day, which, in the course of time, created a serious error in their calculations.

A cycle was then framed at Rome for 84 years, and generally received by the Western church, for it was then thought that in this space of time the moon’s changes would return not only to the same day of the month, but of the week also. Wheatley tells us that, ‘During the time that Easter was kept according to this cycle, Britain was separated from the Roman empire, and the British churches for some time after that separation continued to keep Easter according to this table of 84 years. But soon after that separation, the Church of Rome and several others discovered great deficiencies in this account, and therefore left it for another which was more perfect.’—Book on the Common Prayer, p. 40. This was the Victorian period of 532 years. But he is clearly in error here. The Victorian period was only drawn up about the year 457, and was not adopted by the Church till the Fourth Council of Orleans, A.D. 541.

Now from the time the Romans finally left Britain (A.D. 426), when he supposes both churches to be using the cycle of 84 years, till the arrival of St. Augustine (A.D. 596), the error can hardly have amounted to a difference worth disputing about. And yet the time the Britons kept Easter must have varied considerably from that of the Roman missionaries to have given rise to the statement that they were Quartodecimans, which they certainly were not; for it is a well-known fact that British bishops were at the Council of Nice, and doubtless adopted and brought home with them the rule laid down by that assembly. Dr. Hooke’s account is far more probable, that the British and Irish churches adhered to the Alexandrian rule, according to which the Easter festival could not begin before the 8th of March; while according to the rule adopted at Rome and generally in the West, it began as early as the fifth. ‘They (the Celts) were manifestly in error,’ he says; ‘but owing to the haughtiness with which the Italians had demanded an alteration in their calendar, they doggedly determined not to change.’—Lives of the Archbishops of Canterbury, vol. i. p. 14.

After a good deal of disputation had taken place, with more in prospect, Oswy, King of Northumbria, determined to take the matter in hand. He summoned the leaders of the contending parties to a conference at Whitby, A.D. 664, at which he himself presided. Colman, bishop of Lindisfarne, represented the British church. The Romish party were headed by Agilbert, bishop of Dorchester, and Wilfrid, a young Saxon. Wilfrid was spokesman. The arguments were characteristic of the age; but the manner in which the king decided irresistibly provokes a smile, and makes one doubt whether he were in jest or earnest. Colman spoke first, and urged that the custom of the Celtic church ought not to be changed, because it had been inherited from their forefathers, men beloved of God, &c. Wilfrid followed:

-

‘The Easter which we observe I saw celebrated by all at Rome: there, where the blessed apostles, Peter and Paul, lived, taught, suffered, and were buried.’ And concluded a really powerful speech with these words: ‘And if, after all, that Columba of yours were, which I will not deny, a holy man, gifted with the power of working miracles, is he, I ask, to be preferred before the most blessed Prince of the Apostles, to whom our Lord said, “Thou art Peter, and upon this rock will I build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it; and to thee will I give the keys of the kingdom of heaven†?’

The King, turning to Colman, asked him, ‘Is it true or not, Colman, that these words were spoken to Peter by our Lord?’ Colman, who seems to have been completely cowed, could not deny it. ‘It is true, 0 King.’ ‘Then,’ said the King, ‘can you shew me any such power given to your Columba? ’ Colman answered, ’ No.’ ‘You are both, then, agreed,’ continued the King, are you not, that these words were addressed principally to Peter, and that to him were given the keys of heaven by our Lord?’ Both assented. ‘Then,’ said the King, ‘I tell you plainly, I shall not stand opposed to the door-keeper of the kingdom of heaven; I desire, as far as in me lies, to adhere to his precepts and obey his commands, lest by offending him who keepeth the keys, I should, when I present myself at the gate, find no one to open to me.’

This settled the controversy, though poor honest Colman resigned his see rather than submit to such a decision.

On Easter-day depend all the moveable feasts and fasts throughout the year. The nine Sundays before, and the eight following after, are all dependent upon it, and form, as it were, a body-guard to this Queen of Festivals. The nine preceding are the six Sundays in Lent, Quinquagesima, Sexagesima, and Septuagesima; the eight following are the five Sundays after Easter, the Sunday after Ascension Day, Whit Sunday, and Trinity Sunday.

EASTER CUSTOMS

The old Easter customs which still linger among us vary considerably in form in different parts of the kingdom. The custom of distributing the ‘pace’ or ‘pasche ege,’ which was once almost universal among Christians, is still observed by children, and by the peasantry in Lancashire. Even in Scotland, where the great festivals have for centuries been suppressed, the young people still get their hard-boiled dyed eggs, which they roll about, or throw, and finally eat. In Lancashire, and in Cheshire, Staffordshire, and Warwickshire, and perhaps in other counties, the ridiculous custom of ‘lifting’ or ‘heaving’ is practised.

On Easter Monday the men lift the women, and on Easter Tuesday the women lift or heave the men. The process is performed by two lusty men or women joining their hands across each other’s wrists; then, making the person to be heaved sit down on their arms, they lift him up aloft two or three times, and often carry him several yards along a street. A grave clergyman who happened to be passing through a town in Lancashire on an Easter Tuesday, and having to stay an hour or two at an inn, was astonished by three or four lusty women rushing into his room, exclaiming they had come ‘to lift him.’ ‘To lift me!’ repeated the amazed divine; ‘what can you mean?’ ‘Why, your reverence, we’re come to lift you, ‘cause it’s Easter Tuesday.’ ‘Lift me because it’s Easter Tuesday? I don’t understand. Is there any such custom here?’ ‘Yes, to be sure; why, don’t you know? all us women was lifted yesterday; and us lifts the men today in turn. And in course it’s our rights and duties to lift ‘em.’

After a little further parley, the reverend traveller compromised with his fair visitors for half-a-crown, and thus escaped the dreaded compliment. In Durham, on Easter Monday, the men claim the privilege to take off the women’s shoes, and the next day the women retaliate. Anciently, both ecclesiastics and laics used to play at ball in the churches for tansy-cakes on Eastertide; and, though the profane part of this custom is happily everywhere discontinued, tansy-cakes and tansy-puddings are still favourite dishes at Easter in many parts. In some parishes in the counties of Dorset and Devon, the clerk carries round to every house a few white cakes as an Easter offering; these cakes, which are about the eighth of an inch thick, and of two sizes —the larger being seven or eight inches, the smaller about five in diameter— have a mingled bitter and sweet taste. In return for these cakes, which are always distributed after Divine service on Good Friday, the clerk receives a gratuity- according to the circumstances or generosity of the householder.

“This Land Is My Land; It Isn’t Your Land.”

America, Kevin Costner, Private Property, Yellowstone

“The Injustices of Capitalism”

Capitalism, Left Think, Millennials

Alyssa Ahlgren has some choice words for complaining leftists.

I’m sitting in a small coffee shop near Nokomis trying to think of what to write about. I scroll through my newsfeed on my phone looking at the latest headlines of Democratic candidates calling for policies to “fix†the so-called injustices of capitalism. I put my phone down and continue to look around. I see people talking freely, working on their MacBook’s, ordering food they get in an instant, seeing cars go by outside, and it dawned on me. We live in the most privileged time in the most prosperous nation and we’ve become completely blind to it. Vehicles, food, technology, freedom to associate with whom we choose. These things are so ingrained in our American way of life we don’t give them a second thought. We are so well off here in the United States that our poverty line begins 31 times above the global average. Thirty. One. Times. Virtually no one in the United States is considered poor by global standards. Yet, in a time where we can order a product off Amazon with one click and have it at our doorstep the next day, we are unappreciative, unsatisfied, and ungrateful.

He Embraces His White Guilt

Left Think, Racial Politics, Satire, White Guilt

Jarvis Dupont in the Spectator:

As a child, I was horrifyingly oblivious to what it meant to be a white male. I ignorantly assumed that skin color should never be an issue. I went around treating everyone the same regardless of gender or race. I look back on those days now and cringe. Thank goodness I ‘woke up’ so to speak!

I was lucky to grow up on a moderately large 20,000-acre estate in a 23-bedroom Georgian house which had been in my family for at least six hundred years. For the first few years of my life, I was blissfully unaware of my standing within society. This glorious childhood utopia did not last long.

At the tender age of 12, I watched a film which put it all into perspective: Ratatouille. I remember the impact this movie had on me as if it were yesterday. My mind was awash with confusion. How could a rat control a cook?! Even if it were possible, how is it doing it? It’s simply holding his hair! What method of ungodly witchcraft is being employed here?! Then it hit me. This film was an allegory of slavery. There was no actual rat, it was brilliantly symbolizing white man’s need to dominate. The fact that the ‘rat’ is hidden underneath the chef’s hat cleverly illustrates how white society in America turned a blind eye to the way black people were being exploited. The ‘rat’ is a metaphor for the detached way in which white power was used to oppress African slaves, the ‘food’ it cooks represents the benefits white Americans have enjoyed as a result of this inhumane hierarchical structure. I was gobsmacked that a children’s movie could encapsulate a complex multi-layered issue in such a devastatingly simplistic way. …

I remember that first wave of White Guilt washing over me. It was like an epiphany. I bathed in it, swam in it. Immersed my disgustingly pallid complexion in it until I was spent. Looking back, I’m not ashamed to admit it was an almost erotic experience. From then on, I was transformed. I found myself telling people to ‘educate themselves’, and would begin conversations with ‘FYI’, or ‘Dear fellow white people…’. I was using the word ‘problematic’ at least three hundred times a day, and it was wonderfully cathartic. The first time I called Father a ‘bitch-ass white cracker skank’ was an incredibly liberating experience.

I demanded to be sent to a university for the lower-orders so that I could experience poverty first-hand. After a few heated arguments, Father acquiesced, so long as he could purchase a townhouse nearby for me to live in and set up regular allowance payments to my bank account via direct debit. I reluctantly agreed to all of this on the condition that my allowance would not exceed 5k per month.

I’ve taken surprisingly well to my self-inflicted destitution and university life has proven to be ideal for my new found woke lifestyle. Many of my student chums are also aware of their White Guilt, and we regularly meet up to admonish those who do not acknowledge theirs. Only last weekend we berated a white homeless man sitting outside Taco Bell for his appalling lack of self-awareness regarding not only his own privilege, but his flagrant disrespect towards cultural appropriation. Eventually he became so violently agitated the police came along and forcibly removed him and his filthy blanket from the pavement. Of course, if he were black the police would have shot him dead, so I hope he realized just how privileged he is.

Despite my early awokening, the opulence of my youth is something which still plagues me to this day. I see racial bias all around me. The amount of opportunities I have as a white male are staggering compared to those of a BAME. We need to do more, and I am determined that when I inherit my family’s estate, I will make damn sure I only employ people of color to maintain it.

Samuel Whittemore 1695-1793

American Revolution, Battles of Lexington and Concord, Samuel Whittemore, The Right Stuff

Born in 1695, just 75 years after the first Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock, the stone-cold hardass who would be made a state hero of Massachusetts was first unleashed on colonial America in the 1740s while serving as a Captain in His Majesty’s Dragoons – a badass unit of elite British cavalrymen much-feared across the globe for their ability to impale people on lance-points and then pump their already-dead bodies full of gigantic pistol ammunition that more closely resembled baseballs than the sort of rounds you see packed into Beretta magazines these days. Fighting the French in Canada during the War of Austrian Succession (a conflict that was known here in the colonies as King George’s War because seriously WTF did colonial Americans care about Austrian succession), Whittemore was part of the British contingent that assaulted the frozen shores of Nova Scotia and beat the shit out of the French at their stronghold of Louisbourg in 1745. The 50 year-old cavalry officer went into battle galloping at the head of a company of rifle-toting horsemen, and emerged from the shouldering flames of a thoroughly ass-humped Louisbourg holding a bitchin’ ornate longsword he had wrenched from the lifeless hands of a French officer who had, in Whittemore’s words, “died suddenly”. The French would eventually manage to snake Louisbourg back from the Brits, so thirteen years later, during the Seven Years’ War (a conflict that was known here in the colonies as the French and Indian War because WTF we were fighting the French and the Indians, and also because it lasted nine years instead of seven), Whittemore had to return to his old stomping grounds of Louisburg and ruthlessly beat it into submission once again. Serving under the able command fellow badass British commander James Wolfe, a man who earned his reputation by commanding a line of riflemen who held their lines against a frothing-at-the-mouth horde of psychotic, sword-swinging William Wallace motherfuckers in Scotland (this is a story I intend to tell at a later date), Whittemore once again pummeled the French retarded and stole all of their shit he could get his hands on. He served valiantly during the Second Siege of Louisbourg, pounding the poor city into rubble a second time in an epic bloodbath would mark the beginning of the end for France’s Atlantic colonies – Quebec would fall shortly thereafter, and the French would be chased out of Canada forever. So you can thank Whittemore for that, if you are inclined to do so.

Beating Frenchmen down with a cavalry saber at the age of 64 is pretty cool and all, but Whittemore still wasn’t done doing awesome shit in the name of King George the Third and His Loyal Colonies. Four years after busting up the French for the second time in two decades he led troops against Chief Pontiac in the bloody Indian Wars that raged across the Great Lakes region. Never one to back down from an up-close-and-personal fistfight, it was during a particularly nasty bout of hand-to-hand combat he came into possession of another totally sweet war trophy – an awesome pair of matched dueling pistols he had taken from the body of a warrior he’d just finished bayoneting or sabering or whatever.

After serving in three American wars before America was even a country, Whittemore decided the colonies were pretty damn radical, so he settled down in Massachusetts, married two different women (though not at the same time), had eight kids, and built a house out of the carcasses of bears he’d killed and mutilated with his own two hands. Or something like that.

Now, all of this shit is pretty god damned impressive, but interestingly none of it is actually what Samuel Whittemore is best known for. No, his distinction as a national hero instead comes from a fateful day in mid-April 1775, when the British colonies in the New World decided they weren’t going to take any more of King George’s bullshit and decided to get their American Revolution on. And you can be pretty damn sure that if there were asses to be kicked, Whittemore was going to be one of the men doing the kicking.

So one day a bunch of colonial malcontents got together, formed a battle line, and opened fire on a bunch of redcoats that were pissing them off with their silly Stamp Acts and whatnot. The Brits managed to beat back this militia force at the Battles of Lexington and Concord, but when they heard that a larger force of angry, rifle-toting colonials was headed their way, the English officers decided to march back to their headquarters and regroup. Along the way, they were hassled relentlessly by American militiamen with rifles and angry insults, though no group harassed them more ferociously than Captain Sam Whittemore. When the Redcoats went marching back through his hometown of Menotomy, this guy decided that he wasn’t going to let his advanced age stop him from doing some crazy shit and taking on an entire British army himself. The 80 year old Whittemore grabbed his rifle and ran outside:

Whittemore, by himself, with no backup, positioned himself behind a stone wall, waited in ambush, and then single-handedly engaged the entire British 47th Regiment of Foot with nothing more than his musket and the pure liquid anger coursing through his veins. His ambush had been successful – by this time this guy popped up like a decrepitly old rifle-toting jack-in-the-box, the British troops were pretty much on top of him. He fired off his musket at point-blank range, busting the nearest guy so hard it nearly blew his red coat into the next dimension.

Now, when you’re using a firearm that takes 20 seconds to reload, it’s kind of hard to go all Leonard Funk on a platoon of enemy infantry, but damn it if Whittemore wasn’t going to try. With a company of Brits bearing down in him, he quick-drew his twin flintlock pistols and popped a couple of locks on them (caps hadn’t been invented yet, though I think the analogy still works pretty fucking well), busting another two Limeys a matching set of new assholes. Then he unsheathed the ornate French sword, and this 80-year-old madman stood his ground in hand-to-hand against a couple dozen trained soldiers, each of which was probably a quarter of his age.

…[I]t didn’t work out so well. Whittemore was shot through the face by a 69-caliber bullet, knocked down, and bayonetted 13 times by motherfuckers. I’d like to imagine he wounded a couple more Englishmen who slipped or choked on his blood, though history only seems to credit him with three kills on three shots fired. The Brits, convinced that this man was sufficiently beat to shit, left him for dead kept on their death march back to base, harassed the entire way by Whittemore’s fellow militiamen.

Amazingly, however, Samuel Whittemore didn’t die. When his friends rushed out from their homes to check on his body, they found the half-dead, ultra-bloody octogenarian still trying to reload his weapon and seek vengeance. The dude actually survived the entire war, finally dying in 1793 at the age of 98 from extreme old age and awesomeness. A 2005 act of the Massachusetts legislature declared him an official state hero, and today he has one of the most badass historical markers of all time.

19 April 1775

American Revolution, Battles of Lexington and Concord

“Stand your ground; don’t fire unless fired upon, but if they mean to have a war, let it begin here.”

—Captain John Parker.

By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled,

Here once the embattled farmers stood

And fired the shot heard round the world.

–Ralph Waldo Emerson

200,000 Bees on the Roof of Notre Dame Survived

Bees, Notre Dame Fire

AFP:

Les 200.000 abeilles des ruches de Notre-Dame ont survécu à l’incendie qui a ravagé le toit de la cathédrale lundi, alors que des réactions du monde entier affluent pour s’inquiéter de leur sort.

“Les abeilles sont en vie. Jusqu’à ce matin, vers 11 heures, je n’avais aucune nouvelleâ€, explique à l’AFP l’apiculteur Nicolas Géant qui s’occupe des ruches de Notre-Dame situées sur la sacristie attenante à la cathédrale, ce jeudi 18 avril.

“Au départ, je pensais que les trois ruches avaient brûlé, je n’avais aucune information. Mais j’ai ensuite pu voir sur les images satellites que ce n’était pas le cas et le porte-parole de la cathédrale m’a confirmé qu’elles entraient et sortaient des ruchesâ€, poursuit-il.

Nicolas Géant a reçu des messages et des appels du monde entier de personnes se demandant si les abeilles avaient péri dans les flammes. “C’était inattendu. J’ai reçu des appels d’Europe, bien sûr, mais aussi d’Afrique du Sud, du Japon, des États-Unis et d’Amérique du Sudâ€, dit-il.

En cas d’incendie et dès les premiers signes de fumée, les abeilles se “gorgent†de miel et protègent leur reine. “Cette espèce (l’abeille européenne) n’abandonne pas sa ruche. Elles ne possèdent pas de poumons, mais le CO2 les endortâ€, explique Nicolas Géant, qui espère revoir ses abeilles la “semaine prochaineâ€. Chaque ruche produit en moyenne chaque année 25 kilos de miel, vendu au personnel de Notre-Dame, qui les héberge depuis 2013.

(Rough translation)

The 200,000 bees of the hives of Notre Dame survived the fire that ravaged the roof of the cathedral Monday, while reactions from around the world pour in worrying about their fate.

“The bees are alive. Until this morning, around 11 am, I had no news, “the beekeeper Nicolas Géantwho takes care of the hives of Notre-Dame located on the sacristy adjoining the cathedral explained to the AFP this Thursday 18 April.

“At first, I thought the three hives had burned, I had no information. But then I could see on the satellite images that it was not the case and the spokesman of the cathedral confirmed to me that they had entered and removed the hives,” he went on.

Nicolas Géant has received messages and calls from all over the world asking if the bees had died in the flames. “It was unexpected. I have received calls from Europe, of course, but also from South Africa, Japan, the United States and South America, “he said.

In case of fire and at the first sign of smoke, the bees “gorge on” honey and protect their queen. “This species (the European bee) does not abandon its hive. They do not have lungs, but CO2 puts them to sleep, “says Nicolas Geant, who hopes to see his bees again next week. Each hive produces an average of 25 kilos of honey each year, sold to the staff of Notre-Dame, which has been sheltering them since 2013.

Bear Skull, Human Skull, Broken Rifle

Alaska, Big Game Hunting, Bill Pinnell, Brown Bear, Human Predation

An interesting old photo of Bill Pinnell, half of the famous Pinnell and Tallifson Kodiak bear guides.

Alaska hunting guide Phil Shoemaker:

This photo was found under his bunk after his passing and the speculation is that it was simply one of his pranks.

Living in the same type of wild country, just across the Shelikov straights from Kodiak, I considered posing a similar scene with one of the old bear skulls we have found and a human skull we found at a WWII airplane wreck.

“Simply a Construction Accident”

France, Islam, Notre Dame Fire, Terrorism, The Mainstream Media

Roger Kimball admires the rapidity with which the French authorities definitively determined that Notre Dame fire was an accident and not another case of deliberate arson.

“Auric Goldfinger, in the Ian Fleming novel, dryly observes to James Bond that “Once is happenstance. Twice is coincidence. The third time it’s enemy action.â€

The French investigators have such extraordinary powers of forensic penetration that they can dispense with all such inductive aids to inquiry. Here they have not one, not two or three, but twelve acts of violent desecration in the past month, including an arsonist attack against the second largest church in Paris. Then Notre Dame catches fire—and what a fire it was—on Monday of Holy Week. Even before the fire was brought under control, the authorities ruled out arson. Has the world ever seen a more potent demonstration of investigative prowess?”

————————-

On FB, Matthew Keogh said:

Notre Dame Cathedral Fire, a few facts you should know courtesy of the mainstream media:

1. The exact cause of the blaze is still unknown.

2. The exact cause of the blaze is still unknown, but it has been ruled an accident (despite the fact that the exact cause of the blaze is still unknown).

3. The exact cause of the blaze is still unknown, but Islam is the real victim here.

4. The exact cause of the blaze is still unknown which means the damage has not been thoroughly assessed, but it’s not arson.

5. The exact cause of the blaze is still unknown which means the damage has not been thoroughly assessed, but Macron is setting up an international appeal for funding to rebuild despite not knowing how much is needed because the damage has not been thoroughly assessed.

This is the sort of information you get when journalists are in bed with the politicians.

“Innovation”

Innovation, Language

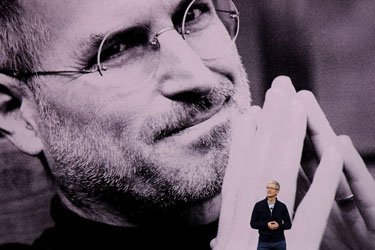

Apple CEO Tim Cook speaks during an Apple special event at the Steve Jobs Theatre on the Apple Park campus on September 12, 2017 in Cupertino, California.

Amusingly, leftist English prof John Patrick Leary, writing in Jacobin, sounds a lot like Edmund Burke or Pope Pius X when he’s denouncing popular contemporary cant about “innovation.”

For most of its early life, the word “innovation†was a pejorative, used to denounce false prophets and political dissidents. Thomas Hobbes used innovator in the seventeenth century as a synonym for a vain conspirator; Edmund Burke decried the innovators of revolutionary Paris as wreckers and miscreants; in 1837, a Catholic priest in Vermont devoted 320 pages to denouncing “the Innovator,†an archetypal heretic he summarized as an “infidel and a sceptick at heart.†The innovator’s skepticism was a destructive conspiracy against the established order, whether in heaven or on Earth. And if the innovator styled himself a seer, he was a false prophet.

By the turn of the last century, though, the practice of innovation had begun to shed these associations with plotting and heresy. A milestone may have been achieved around 1914, when Vernon Castle, America’s foremost dance instructor, invented a “decent,†simplified American version of the Argentine tango and named it “the Innovation.â€

“We are now in a state of transmission to more beautiful dancing,†said Mamie Fish, the famed New York socialite credited with naming the dance. She told the Omaha Bee in 1914 that “this latest is a remarkably pretty dance, lacking in all the eccentricities and abandon of the ‘tango,’ and it is not at all difficult to do.†No longer a deviant sin, innovation — and “The Innovation†— had become positively decent.

The contemporary ubiquity of innovation is an example of how the world of business, despite its claims of rationality and empirical precision, also summons its own enigmatic mythologies. Many of the words covered in my new book, Keywords, orbit this one, deriving their own authority from their connection to the power of innovation.

The value of innovation is so widespread and so seemingly self-evident that questioning it might seem bizarre — like criticizing beauty, science, or penicillin, things that are, like innovation, treated as either abstract human values or socially useful things we can scarcely imagine doing without. And certainly, many things called innovations are, in fact, innovative in the strict sense: original processes or products that satisfy some human need.

A scholar can uncover archival evidence that transforms how we understand the meaning of a historical event; an automotive engineer can develop new industrial processes to make a car lighter; a corporate executive can extract additional value from his employees by automating production. These are all new ways of doing something, but they are very different somethings. Some require a combination of dogged persistence and interpretive imagination; others make use of mathematical and technical expertise; others, organizational vision and practical ruthlessness.

But innovation as it is used most often today comes with an implied sense of benevolence; we rarely talk of innovative credit-default swaps or innovative chemical weapons, but innovations they plainly are. The destructive skepticism of the false-prophet innovator has been redeemed as the profit-making insight of the technological visionary.

Innovation is most popular today as a stand-alone concept, a kind of managerial spirit that permeates nearly every institutional setting, from nonprofits and newspapers to schools and children’s toys. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines innovation as “the alteration of what is established by the introduction of new elements or forms.†The earliest example the dictionary gives dates from the mid-sixteenth century; the adjectival “innovative,†meanwhile, was virtually unknown before the 1960s, but has exploded in popularity since.

The verb “to innovate†has also seen a resurgence in recent years. The verb’s intransitive meaning is “to bring in or introduce novelties; to make changes in something established; to introduce innovations.†Its earlier transitive meaning, “To change (a thing) into something new; to alter; to renew†is considered obsolete by the OED, but this meaning has seen something of a revival. This was the active meaning associated with conspirators and heretics, who were innovating the word of God or innovating government, in the sense of undermining or overthrowing each.

The major conflict in innovation’s history is that between its formerly prohibited, religious connotation and the salutary, practical meaning that predominates now. Benoît Godin has shown that innovation was recuperated as a secular concept in the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth, when it became a form of worldly praxis rather than theological reflection. Its grammar evolved along with this meaning. Instead of a discrete irruption in an established order, innovation as a mass noun became a visionary faculty that individuals could nurture and develop in practical ways in the world; it was also the process of applying this faculty (e.g., “Lenovo’s pursuit of innovationâ€).