Category Archive 'Book Reviews'

16 Jul 2018

Adriana Ivancich, Hemingway, and friend in Finca Vigia, Cuba.

The life of Ernest Hemingway remains sufficiently fascinating that a new book has appeared, Andrea Di Robilant’s Autumn in Venice: Ernest Hemingway and His Last Muse, chronicling the great man’s not-necessarily-ever-consummated infatuation at age 49 with an 18-year-old Italian countess.

That inappropriate relationship, ironically enough, provided the gravamen of Ernest Hemingway’s worst, only genuinely bad, downright embarrassing novel, Across the River and into the Trees.

Rafia Zakaria, a columnist for Pakistan’s largest newspaper (!), reviews the story of Hemingway’s Last Girl with chilly feminist scorn for the dirty old man’s incestuous infatuation with a younger woman he called “daughter,” and wrathfully concludes with a stern determination to call literary geniuses to account for their “sins” and their “misogyny” on behalf of the “maligned women” in their lives. Take that, Papa, you beast!

It all began because of a comb. Sometime after four in a dark and cold Italian morning, a young woman accompanied a band of men to a duck shoot. After it was over and the frigid hunters sat by the fire, the eighteen-year old Adriana Ivancich, the only woman in the gathering, asked for a comb for her long black hair. Nearly all the men in the party ignored her and kept up their talking. Ernest Hemingway, however, was not ever one to let a lady go unattended. After rooting around in his pockets, he produced a comb, broke it in half and gave it to her. It was a very Hemingway gesture, chivalrous and theatric and meant very much to be memorable. (63)

It would be. The Hemingway that was at the duck shoot that frigid morning may have been a rotund and aging man who presided over slightly slacking but still eminent literary career, but he remained ever amenable to the charms of women. The duck shoot was not even the first time the two had met; that had happened the night before, when Hemingway, along with Adriana’s cousin Nanuk Franchetti, the host of the duck shoot, had picked her up by the side of road. …

Autumn in Venice… is a chronicle of sorts of this last affair. Hemingway, then very much married to Mary Welsh Hemingway, who had ostensibly “stolen†him away from Martha Gellhorn, romanced Adriana right under his wife’s nose. The story of Adriana and Hemingway was initially interposed between Mary Hemingway’s “major shopping spreesâ€, “hours of sightseeing†and yet more shopping trips. It ended with Adriana and almost her entire family installed in the Hemingway’s home, fixtures at the caviar laden, booze filled evenings that oiled Hemingway’s daily grind.

In subject and content, the affair with Adriana, and indeed with Venice itself, was rather predictable and even banal. Hemingway had always craved the euphoria of being in love and had chased it all his life without concern for the cost it imposed on existing relationships and, as it were, his wives.

13 Jul 2018

Peter Thonneman wittily reviews David Stuttard’s new Nemesis: Alcibiades and the Fall of Athens.

Of all personality traits, charisma is the hardest to appreciate at second hand. We read Cicero’s letters and can instantly tell that he was vain, insecure and ferociously clever; we read scraps of Samuel Johnson’s conversation in Boswell’s biography and know at once that he was magnificent, lovable and desperately unhappy. But as to what it was like to have Lord Byron turn the full force of his attention onto you – well, we have no conceivable way of knowing. We just have to trust his contemporaries that it felt like ‘the opening of the gate of heaven’.

This causes problems for a biographer of Alcibiades. On the face of it, the man was utterly insufferable. Born in around 450 BC into one of the oldest and richest families of ancient Athens, Alcibiades was the only Old Etonian (as it were) to play a leading role in the late-fifth-century radical democracy. The account of his childhood in Plutarch’s Life of Alcibiades suggests a bad case of antisocial personality disorder: biting during wrestling, mutilating dogs, punching his future father-in-law in the face for a dare. His later political career makes Boris Johnson seem like a man of firm and unbending principle. Exiled from Athens in 415 BC over some particularly odious Bullingdon Club antics, Alcibiades promptly sold his services to Sparta (where he seduced the king’s wife) before double-crossing both sides and wheedling his way into the court of a Persian satrap.

But Alcibiades, like Byron, clearly had that indefinable something. One catches a glimpse of it in the unforgettable last scene of Plato’s Symposium, when he crashes into the room, blind drunk, flirting with everything on legs, shouting about his love for Socrates. Thucydides captures it in his report of Alcibiades’s speech whipping up the Athenian assembly to vote for the disastrous Sicilian expedition of 415 BC – an extraordinary stew of egotistic bragging (about how successful his racehorses are), mendacious demagoguery and brilliantly acute strategic thinking. The unwashed Athenian masses, not usually prone to atavistic toff-grovelling, absolutely adored him: when Alcibiades finally returned to Athens in 407 BC after eight years of exile, sailing coolly into Piraeus on a ship with purple sails, they welcomed him back with paroxysms of joy.

Behind the Peloponnese-sized ego, Alcibiades was a general of spectacular genius – when he could be bothered. In 410 BC, shortly after his controversial reinstatement as admiral of the Athenian navy (on the back of a bogus promise of Persian support), he wiped out the entire Spartan fleet at the Battle of Cyzicus; two years later, through sheer chutzpah, he captured the city of Selymbria near Byzantium with only fifty soldiers, and without striking a blow. When things went wrong – as in 406 BC, after a disastrous campaigning season in the eastern Aegean – he showed an infuriating ability to wriggle out of trouble. His final years (406–404 BC) were spent once again in exile from Athens, holed up in a private castle on the Gallipoli peninsula. The circumstances of his death are still shrouded in mystery. One story tells that he died in the remote mountains of central Turkey at the hands of the brothers of a Phrygian noblewoman whom he had decided to seduce. This is, I fear, all too believable.

RTWT

17 Oct 2017

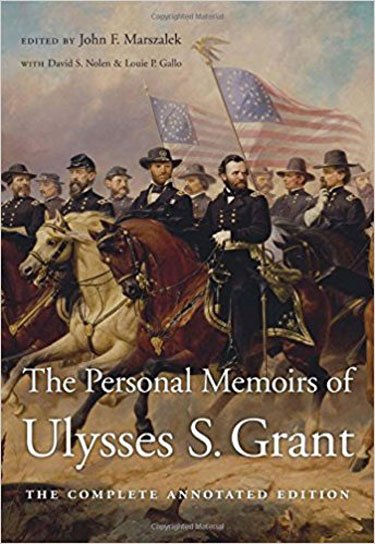

T.J. Stiles reviews Harvard University Press’s new annotated edition of Grant’s Memoirs.

At this distance, it’s hard to see the appeal of McClellan’s self-regard and concocted grandeur, because he sounds like an ass. It’s easier to like Grant. In his memoirs, Grant expresses his “rigorous distaste†for “ceremony, theater and oratory†(in the words of the historian John Keegan) by describing two generals of the war with Mexico, in which he fought bravely as a young West Point graduate. He admires the unaffected Zachary Taylor, who “dressed himself entirely for comfort,†in civilian clothes. But Winfield Scott “always wore all the uniform . . . allowed by law,†Grant observes: “dress uniform, cocked hat, aiguillettes†— loops of braid at the shoulder — “saber, and spurs.†Grant respects Scott’s ability but not his language, noting he was “not averse to speaking of himself, often in the third person, and he could bestow praise upon the person he was talking about without the least embarrassment.â€

Photo

That’s funny — almost Calvin Trillin funny — but we hear the bite. As modest and decent as Grant was, he appears to have clutched in his pocket a little squirming snake of resentment. After the Mexican War, he failed in the Army because of his secret shame, alcoholism, at a time when temperance was a major cultural force; he scrabbled hard in the years that followed, trapped in a desert of poverty. He returned to duty in the Civil War and won victory after victory, rising so high that Congress resorted to creating new ranks for him. His enemies retaliated by making his shame public, charging him with drunkenness. He felt the scorn of patricians like Henry Adams, who concluded he was “pre-intellectual . . . and would have seemed so even to the cave-dwellers.†Here and there, Grant shows how much it hurt. In cutting Scott, he goes beyond a mere lack of affectation into positive derision, mocking the pretensions of the refined society that mocked him.

“Perhaps never has a book so objective in form seemed so personal in every line,†Edmund Wilson observed, and I agree. But I disagree that Grant’s voice is “aloof and dispassionate.†Pain flickers behind the stolid pillars of the memoirs. He reflects his internal state off external surfaces, as with Taylor and Scott. Early on, he describes how as a boy he botched a negotiation for a horse — a telling anecdote, as financial failures agonized him — and the ensuing ridicule. “Boys enjoy the misery of their companions, at least village boys in that day did; and in later life I have found that all adults are not free from the peculiarity.â€

He armored himself with simplicity. Grant’s style is strikingly modern in its economy. It stood out in that age of clambering, winding prose, with shameless sentences like lines of thieves in a marketplace, grabbing everything in reach and stuffing it all into their sacks. Indeed, Grant adhered to Adams’s own instructions to the staff of the North American Review: “Strike out all superfluous words, and especially all needless adjectives.†Wilson observed, “Every word that Grant writes has its purpose, yet everything seems understated.â€

Authenticity is not perfect honesty, of course. Grant cannot always escape the impulse to put things in a favorable light, and he remembers his detractors. “The most confident critics are generally those who know the least about the matter criticized,†he writes. That defensive tone is uncharacteristic, though it’s revealing.

The Civil War rages for most of his book, and Grant proves an exemplary military narrator. He provides context clearly, even after he becomes general in chief, operating on a national scale. He makes his strategy sound like common sense, not genius. We feel his strength of will, from the dreadful first day of Shiloh to the great risk of his Vicksburg operation and beyond. He knew, too, how to shape the reader’s experience. He opens Chapter 50 with these two sentences: “Soon after midnight, May 3d–4th, the Army of the Potomac moved out from its position north of the Rapidan, to start upon that memorable campaign, destined to result in the capture of the Confederate capital and the army defending it. This was not to be accomplished, however, without as desperate fighting as the world has ever witnessed; not to be consummated in a day, a week, a month or a single season.†He delivers so much dread and anticipation with those words, at just the right place.

Grant’s preface alludes to the fact that he wrote as he was dying cruelly of throat cancer, after a swindler had bankrupted and humiliated him. Remarkably, that’s irrelevant to the text, which any writer could count as a triumph.

RTWT

13 Jun 2017

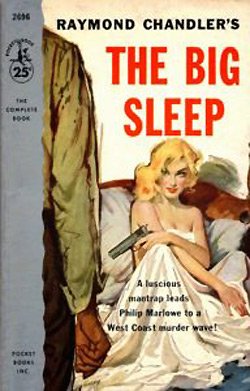

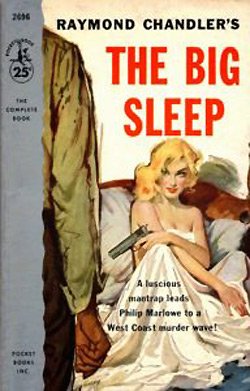

Literary Hub republishes the original New York Times reviews of three Ray Chandler mystery novels.

Isaac Anderson, The New York Times, February 12, 1939:

Most of the characters in this story are tough, many of them are nasty and some of them are both. Philip Marlowe, the private detective who is both the narrator and the chief character, is hard: he has to be hard to cope with the slimy racketeers who are preying on the Sternwood family. Nor do the Sternwoods themselves, particularly the two daughters, respond to gentle treatment. Spoiled is much too mild a term to describe these two young women. Marlowe is working for $25 a day and expenses and he earns every cent of it. Indeed, because of his loyalty to his employer, he passes up golden opportunities to make much more. Before the story is done Marlowe just misses being an eyewitness to two murders and by an even narrower margin misses being a victim. The language used in this book is often vile, at times so filthy that the publishers have been compelled to resort to the dash, a device seldom employed in these unsqueamish days. As a study in depravity, the story is excellent, with Marlowe standing out as almost the only fundamentally decent person in it.â€

RTWT

16 Sep 2016

Hillary’s new campaign book has unaccountably been unfavorably received by the Amazon reading audience, gathering 83% 1-star unfavorable reviews.

But there was at least one astute reader capable of appreciating it. DB raves:

5.0 out of 5 stars This book is a key that unlocks doors to life!!,

September 15, 2016 By DB

What a fantastic book! I see that Amazon has this for under $20, but I paid slightly more. I bought this directly from the Clinton foundation for $3.5 million. Once I read this book it’s like everything in my life clicked. The state department released funds from an “associate” of mine who for some odd reason was mistakenly put on the terrorist watchlist. He then invested in my “housing development” project in Saudi Arabia. Also 14 of my relatives were able to get permanant resident status and my niece got a job at a US Embassy! I suppose I could’ve saved some money by buying the version from Amazon, but by buying directly from the Clinton foundation I got a special edition that is much thicker and has pages hollowed out for future “uses”. I hope this book has an audio version because I would love to pay for play…ing it.

09 May 2016

Christopher Bray calls Daniel Blue’s forthcoming (in June) biography of the young philosopher The Making of Friedrich Nietzsche: The Quest for Identity, 1844-1869 “lacklustre,” but since he’s wrong about the survival of the photo of military Fred with sword, who knows what else he’s wrong about?

(The current price quoted by Amazon is awfully steep. Let’s hope that a better deal becomes available when the book is actually released.)

Had you been down at Naumburg barracks early in March 1867, you might have seen a figure take a running jump at a horse and thud down front first on the pommel with a yelp. This was Friedrich Nietzsche, midway through his 22nd year and, thanks to a sickly childhood, no stranger to hospitals. The doctors were obliged to operate, and Nietzsche lost several ribs and part of his sternum, leaving him not so much pigeon-chested as angle-grinded. Once recovered, he celebrated by having his picture taken in full uniform, sabre at the ready, glaring at the ‘miserable photographer’ like a warrior set for battle. Alas for comedy, this portrait is lost to history.

Daniel Blue has no such regrets. He is convinced the photo would have been ‘unflattering’ — though nowhere near as unflattering as the picture Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche painted of her brother after his death in 1900. …

22 Jan 2015

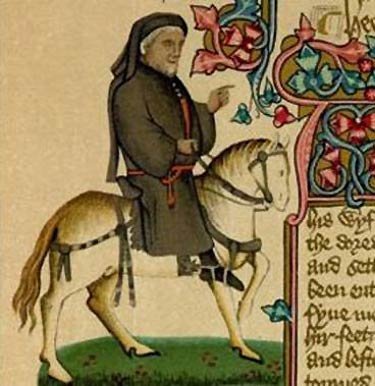

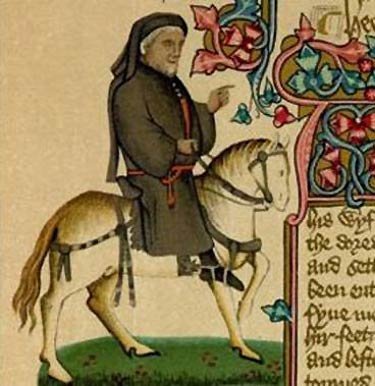

Geoffrey Chaucer from the Ellesmere Manuscript.

Stevie Davies reviews Paul Strohn’s microbiography: Chaucer’s Tale: 1386 and the Road to Canterbury in The Independent.

Strohm centres on a single year, 1386, at the end of which Chaucer “suddenly found himself without a patron, without a faction, without a dwelling, without a job … without a city.”

Exiled from London and his literary circle, Strohm’s Chaucer lost an audience, in an age before the printing press, when poetry in manuscript was read aloud in performance. The book’s compelling thesis is that Chaucer’s loss generated the invention of a “portable audience” within The Canterbury Tales: the pilgrims themselves. …

One of Chaucer’s overarching themes is the volatility of fortune, whose reversals – if we are wise – teach us “to maken virtu of necessitee”. Strohm’s Chaucer is essentially a small player in a world of venal power politics, “a politician of limited gifts, and not much of a factionalist either”. A loyalist of Richard II, he’d risen by espousing the long-term losing party. Esquire to the king, Chaucer had made an advantageous marriage. But he and his higher-ranking wife, Philippa de Roet, sister to John of Gaunt’s mistress, Katherine Swynford, lived apart and his association with the loathed Gaunt jeopardised him.

Deployed by his political masters to the post of controller of wool custom, Chaucer had the unenviable job of monitoring the activities of “some of the richest and best connected and least scrupulous crooks on the face of his planet”. Strohm’s portrait of the collector of the lucrative wool custom, corrupt magnate Nicholas Brembre, is formidable. When the royalist faction secured Chaucer’s election to the 1386 Parliament, and Brembre’s wheel came thundering down, so did Chaucer’s. His grace and favour apartment was forfeit. Strohm assesses Chaucer’s withdrawal from public life as “a matter of constrained choice”. Chaucer became “a wanderer in Kent, with no fixed job and insufficient income”. …

Losing “that thick and involving texture of London life” meant forfeit not only of discomfort but of stimulation and conviviality. The listening audience Chaucer now lacked he invented as a fellowship of pilgrims: “Chaucer’s varied cast of rogues, pitchmen, scammers … divines, social snobs, humble toilers [is] a miracle of imaginative inclusion.” …

From the misfortune of 1386, Chaucer moved towards a sense of authorial identity, preparing his literary legacy for generations to come. The pilgrims mediated “between Chaucer and the extended public he has begun to imagine”. The poet’s humiliated exile, Strohm compellingly suggests, is part of the deep story of how The Canterbury Tales came into being.

02 Aug 2014

Tyler Cowen and Bryan Caplan have been re-reading Catcher in the Rye (so we don’t have to).

TC:

Back then, if you didn’t use your prostitute and then tried to underpay her, she would call you a “crumb-bum. …

[W]hat the novel is really about… is impotence and also post-traumatic stress disorder. …

There is a corniness to how people thought and spoke back then which the book captures remarkably well. …

I expected not to like the re-read, but overall I thought it was pretty damn good and almost universally misunderstood.

———————-

BC:

Other than losing his brother Allie, Holden has no external problems. He is a rich kid living in the most amazing city in the world. Rather than appreciating his good fortune or trying to make the most of his bountiful opportunities, Holden seeks out fruitless conflict. If you still doubt that happiness fundamentally reflects personality, not circumstances, CITR can teach you something. …

Although I was a teen-age misanthrope, anti-hero Holden Caulfield is more dysfunctional than I ever was. My dream was for everyone I disliked to leave me alone. Holden, in contrast, habitually seeks out the company of people he dislikes, then quarrels with them when they act as expected. …

Even if Holden’s enduring antipathy for “phonies” were justified, it’s hard to see why the epithet applies to most of its targets….

For Holden, the main symptom of phoniness is that someone appears to like something Holden doesn’t. But he never wonders, “Is it possible that other people sincerely like stuff I don’t?”

If phonies are your biggest problem, your problems are none too serious. …

I doubt Salinger was being Straussian. Like most of CITR’s fans, he thought Holden has important things to teach us. Yet the book’s deepest and most important lesson is that Holden’s thoughts are profoundly shallow and unimportant. The Holdens of the world should stop talking and start listening, for they have little to teach and much to learn.

Hat tip to Walter Olson.

15 Jul 2014

William Deresiewicz

Critic, and former Yale professor, William Deresiewicz did a really excellent job of savaging Lawrence Buell’s The Dream of the Great American Novel

Buell’s book tells us a great deal about American fiction. What it also tells us, in its every line, is much of what is wrong with academic criticism. We can start with the language…. Here is a fair sample of Buell’s prose:

Admittedly any such dyadic comparison risks oversimplifying the menu of eligible strategies, but the risk is lessened when one bears in mind that to envisage novels as potential GANs is necessarily to conceive them as belonging to more extensive domains of narrative practice that draw on repertoires of tropes and recipes for encapsulating nationness of the kinds sketched briefly in the Introduction—such that you can’t fully grasp what’s at stake in any one possible GAN without imagining the individual work in multiple conversations with many others, and not just U.S. literature either.

That’s one sentence. There is an idea in there somewhere, but it can’t escape the prose—the Byzantine syntax and Latinate diction, the rhetorical falls and grammatical stumbles. Schmidt’s smooth sentences urge us ever onward. Buell’s, like boulders, say stop, go back.

The truth is that by academic standards, Buell’s writing isn’t especially bad—which makes him, as an instance, even worse. By the same token, he isn’t noxiously ideological in the current style, isn’t an “-ist†with an ax to grind or swing—all the more reason to deplore how thoroughly (it seems, reflexively) his book bespeaks the reigning ideologies. Buell, whose careful terror seems to be the possibility of saying something politically incorrect—the book does so much posturing, you think it’s going to throw its back out—appears to have absorbed every piety in the contemporary critical hymnal. You can see him fairly bowing to them in his introduction, as if by way of ritual preparation. There they are, propitiated one by one—Ethnicity, Globalism, Anti-Canonicity, Anti-Essentialism—like idols in the corners of a temple.

The frame of mind controls the readings. Novels aren’t stories, for Buell, works of invention with their own disparate purposes and idiosyncratic ends. They’re “interventions†into this or that political debate—usually, of course, concerning gender, race, or class, as if everyone in history had the same priorities as the English professors of 2014. Nearly every book is scored against today’s approved enlightened norms. Gone With the Wind loses points for “containing†Scarlett and embodying an “atavistic conception of human rights†but wins a few back for being “even more transnationally attuned than Absalom,†exhibiting “maverick tendencies in some respects as pronounced as Faulkner’s,†and engaging in “an act of feminist exorcism that Absalom can’t imagine.†Go team!

In the case of Uncle Tom’s Cabin—a book that makes this kind of reading sweat, being heroically progressive by the standards of its day but embarrassing by ours—pages are spent parsing its exact degree of virtue. Witnesses are called:

Here, as critic Lori Merish delicately puts it, Stowe “fails to imagine African Americans as full participant citizens in an American democracy.†George Harris’s grand design to Christianize Africa looks suspiciously imperialistic to boot, veering Stowe’s antislavery critique in the direction of what Amy Kaplan trenchantly calls “manifest domesticity.â€

I feel as if we’re back in Salem. Maybe he should have just thrown the book in the water to see if it would float. Buell is a person, one should say, who uses terms like cracker, redneck, and white trash without self-consciousness or irony, which makes his moral teleology all the more repulsive—his assumption (and it’s hardly his alone) that all of history has been leading up to the exalted ethical state of the contemporary liberal class.

The one kind of standard that Buell will not permit himself is an aesthetic one. Like many academics now, he’d rather cut his tongue out than admit in public that he thinks a book is good or bad.

13 Jul 2014

Michael Robbins, at Slate, reviews Nick Spencer’s Atheists: The Origin of the Species, which seems to constitute a well-deserved attack on the “New Atheists,” i.e., the smug, self-congratulatory secular materialists of the Richard Dawkins-ilk.

Nietzsche realized that the Enlightenment project to reconstruct morality from rational principles simply retained the character of Christian ethics without providing the foundational authority of the latter. Dispensing with his fantasy of the Ãœbermensch, we are left with his dark diagnosis. To paraphrase the Scottish philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, our moral vocabulary has lost the contexts from which its significance derived, and no amount of Dawkins-style hand-waving about altruistic genes will make the problem go away. (Indeed, the ridiculous belief that our genes determine everything about human behavior and culture is a symptom of this very problem.)

The point is not that a coherent morality requires theism, but that the moral language taken for granted by liberal modernity is a fragmented ruin: It rejects metaphysics but exists only because of prior metaphysical commitments. A coherent atheism would understand this, because it would be aware of its own history. Instead, trendy atheism of the Dawkins variety has learned as little from its forebears as from Thomas Aquinas, preferring to advance a bland version of secular humanism. Spencer quotes John Gray, a not-New atheist: “Humanism is not an alternative to religious belief, but rather a degenerate and unwitting version of it.†How refreshing would be a popular atheism that did not shy from this insight and its consequences.

It is, I suppose, perversely amusing, and confirming of Chesterton’s prediction that, post Religion, people will not believe in nothing, but will believe in anything, that the typical contemporary enlightened elite position involves both the contemptuous rejection of traditional religion and the uncritical acceptance of an even-more-simplistic catechism composed of sentimental humanitarianism constituting a sort of attenuated Christianity, sexually-emancipated but even more enthusiastic about ressentiment.

08 Jun 2014

William Burroughs, 1914-1997

Jesse Walker, reviewing Call Me Burroughs, the new biography by Barry Miles, in Reason Magazine, finds the avante-garde author inconsistent about siding with the Left or the Right, but consistently anti-authoritarian.

Burroughs’ worldview was miles from the peace-and-love socialism that our cultural clichés tell us to expect from a hippie hero. In 1949, according Barry Miles’ new biography Call Me Burroughs, he complained to Kerouac that “we are bogged down in this octopus of bureaucratic socialism.” When he was a landlord in New Orleans he sent Ginsberg a rant against rent control, and when he found himself owning a farm in Texas he gave Ginsberg an earful about the evils of the minimum wage. Eventually he departed for Mexico, and there he wrote to Ginsberg again. “I am not able to share your enthusiasm for the deplorable conditions which obtain in the U.S. at this time,” he told his leftist friend. “I think the U.S. is heading in the direction of a Socialistic police state similar to England, and not too different from Russia….At least Mexico is no obscenity ‘Welfare’ State, and the more I see of this country the better I like it. It is really possible to relax here where nobody tries to mind your business for you.” He added that Westbrook Pegler, a hard-right pundit who would soon be a vocal defender of Sen. Joe McCarthy, was “the only columnist, in my opinion, who possesses a grain of integrity.”

Two decades later, covering the Democratic Party’s bloody 1968 convention for Esquire, Burroughs manifested a more left-wing aura. A day after his arrival he donned a McCarthy button—the antiwar insurgent candidate Eugene McCarthy, that is, not Pegler’s pal Joe. When cops started assaulting protesters outside the convention hall, Burroughs immediately aligned himself with the radicals in the streets, declaring in a public statement that the “police acted in the manner of their species” and asking, “Is there not a municipal ordinance that vicious dogs be muzzled and controlled?” He then helped lead an illegal march that ran straight into a contingent of cops and National Guardsmen.

In doing this, he was not merely supporting the protesters’ civil liberties. He was aligning himself with one side of what he saw as a grand conflict. “This is a revolution,” he wrote in a 1970 article for the East Village Other, “and the middle will get the squeeze until there are no neutrals there.” Still later in his life, he would identify “American capitalism” as his foe, specifying: “the American Tycoon…William Randolph Hearst, Vanderbilt, Rockefeller, that whole stratum of American acquisitive evil. Monopolistic, acquisitive evil.”

Burroughs’ influences ranged from Pegler to the ultra-left Situationist International, but the most important early source for his worldview was a man not normally thought of as a political writer at all. Jack Black was a former hobo and burglar whose memoir You Can’t Win engrossed the teenaged Burroughs, leaving a lasting impact on both his outlook and his literary voice. (Black’s first publication, a newspaper serial titled “The Big Break at Folsom,” was ghostwritten by a young reporter named Rose Wilder Lane, who would later play a formative role in the American libertarian movement.) It was Black’s description of an underground code—and his scattered references to the beggars and outlaws who embraced that code as an extended “Johnson Family”—that gave Burroughs’ rebellious streak an ideological framework.

A Johnson “just minds his own business of staying alive and thinks that what other people do is other people’s business,” Burroughs wrote in his 1985 book The Adding Machine. “Yes, this world would be a pretty easy and pleasant place to live in if everybody could just mind his own business and let others do the same. But a wise old black faggot said to me years ago: ‘Some people are shits, darling.'” In 1988, penning a preface for a reprint of Black’s book, Burroughs offered this account of the world’s core conflict: “A basic split between shits and Johnsons has emerged.”

Read the whole thing.

23 May 2014

One special bane connected with modern liberal society’s regime of excessive tolerance is the ease with which the sexually inverted neurotic can rise from his knees on the public lavatory floor to ascend his own personal pulpit in order to impersonate the post-menopausal female moral authority figure and social reformer.

Glenn Greenwald, for instance, is a particularly resilient example. Greenwald succesfully survived a scandal which resulted from his exposure for having persistently used “sock puppet” false identities to lavish praise on his own blog postings. He more recently attached himself to the cause of “whistle blowers” like Edward Snowden and acted as go-between between the latter and Establishment newspapers. Pimping US Intelligence secrets to the Guardian and the Times is the kind of thing which, in today’s world, makes one a hero in certain circles, and the next thing you knew Ebay founder Pierre Omidyar was writing a check for $250 million to buy Greenwald his own media organization. Who better to manage such a thing than the man renowned as “the left’s most dishonest blogger?”

Even Michael Kinsley cannot abide Greenwald’s abrasive sanctimony, and Kinsley took the occasion of the publication of Green wald’s recent Snowden book, No Place to Hide, to carpet bomb the scoundrel with a scathing review published, amusingly enough, in the same New York Times.

“My position was straightforward,†Glenn Greenwald writes. “By ordering illegal eavesdropping, the president had committed crimes and should be held accountable for them.†You break the law, you pay the price: It’s that simple.

But it’s not that simple, as Greenwald must know. There are laws against government eavesdropping on American citizens, and there are laws against leaking official government documents. You can’t just choose the laws you like and ignore the ones you don’t like. Or perhaps you can, but you can’t then claim that it’s all very straightforward.

Greenwald was the go-between for Edward Snowden and some of the newspapers that reported on Snowden’s collection of classified documents exposing huge eavesdropping by the National Security Agency, among other scandals. His story is full of journalistic derring-do, mostly set in exotic Hong Kong. It’s a great yarn, which might be more entertaining if Greenwald himself didn’t come across as so unpleasant. Maybe he’s charming and generous in real life. But in “No Place to Hide,†Greenwald seems like a self-righteous sourpuss, convinced that every issue is “straightforward,†and if you don’t agree with him, you’re part of something he calls “the authorities,†who control everything for their own nefarious but never explained purposes.

Reformers tend to be difficult people. But they come in different flavors. There are ascetics, like Henry James’s Miss Birdseye (from “The Bostoniansâ€), “who knew less about her fellow creatures, if possible, after 50 years of humanitary zeal, than on the day she had gone into the field to testify against the iniquity of most arrangements.â€

There are narcissists like Julian Assange, founder of WikiLeaks. These are self-canonized men who feel that, as saints, they are entitled to ignore the rules that constrain ordinary mortals. Greenwald notes indignantly that Assange was being criticized along these lines “well before he was accused of sex crimes by two women in Sweden.†(Two decades ago the British writer Michael Frayn wrote a wonderful novel and play called “Now You Know,†about a character similar to Assange.)

Then there are political romantics, played in this evening’s performance by Edward Snowden, almost 31 years old, with the sweet, innocently conspiratorial worldview of a precocious teenager. He appears to yearn for martyrdom and, according to Greenwald, “exuded an extraordinary equanimity†at the prospect of “spending decades, or life, in a supermax prison.â€

And Greenwald? In his mind, he is not a reformer but a ruthless revolutionary — Robespierre, or Trotsky. The ancien régime is corrupt through and through, and he is the man who will topple it. Sounding now like Herbert Marcuse with his once fashionable theory of “repressive tolerance,†Greenwald writes about “the implicit bargain that is offered to citizens: Pose no challenge and you have nothing to worry about. Mind your own business, and support or at least tolerate what we do, and you’ll be fine. Put differently, you must refrain from provoking the authority that wields surveillance powers if you wish to be deemed free of wrongdoing. This is a deal that invites passivity, obedience and conformity.â€

Continue reading the main story

Throughout “No Place to Hide,†Greenwald quotes any person or publication taking his side in any argument. If an article or editorial in The Washington Post or The New York Times (which he says “takes direction from the U.S. government about what it should and shouldn’t publishâ€) endorses his view on some issue, he is sure to cite it as evidence that he is right. If Margaret Sullivan, the public editor (ombudsman, or reader representative) of The Times, agrees with him on some controversy, he is in heaven. He cites at length the results of a poll showing that more people are coming around to his notion that the government’s response to terrorism after 9/11 is more dangerous than the threat it is designed to meet.

Greenwald doesn’t seem to realize that every piece of evidence he musters demonstrating that people agree with him undermines his own argument that “the authorities†brook no dissent. No one is stopping people from criticizing the government or supporting Greenwald in any way. Nobody is preventing the nation’s leading newspaper from publishing a regular column in its own pages dissenting from company or government orthodoxy. If a majority of citizens now agree with Greenwald that dissent is being crushed in this country, and will say so openly to a stranger who rings their doorbell or their phone and says she’s a pollster, how can anyone say that dissent is being crushed? What kind of poor excuse for an authoritarian society are we building in which a Glenn Greenwald, proud enemy of conformity and government oppression, can freely promote this book in all media and sell thousands of copies at airport bookstores surrounded by Homeland Security officers?

Read the whole thing.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Book Reviews' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|