Category Archive 'Culture'

23 Dec 2024

In Tablet Magazine, David Samuels

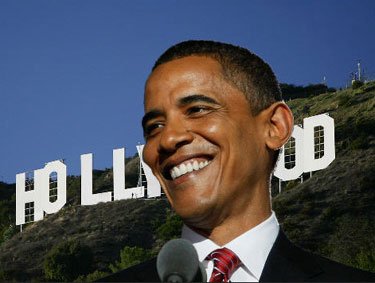

During the Trump years, Obama used the tools of the digital age to craft an entirely new type of power center for himself, one that revolved around his unique position as the titular, though pointedly never-named, head of a Democratic Party that he succeeded in refashioning in his own image—and which, after Hillary’s loss, had officially supplanted the “centrist” Clinton neoliberal machine of the 1990s. The Obama Democratic Party (ODP) was a kind of balancing mechanism between the power and money of the Silicon Valley oligarchs and their New York bankers; the interests of bureaucratic and professional elites who shuttled between the banks and tech companies and the work of bureaucratic oversight; the ODP’s own sectarian constituencies, which were divided into racial and ethnic categories like “POC,” “MENA,” and “Latinx,” whose bizarre bureaucratic nomenclature signaled their inherent existence as top-down containers for the party’s new-age spoils system; and the world of billionaire-funded NGOs that provided foot-soldiers and enforcers for the party’s efforts at social transformation.

It was the entirety of this apparatus, not just the ability to fashion clever or impactful tweets, that constituted the party’s new form of power. But control over digital platforms, and what appeared on those platforms, was a key element in signaling and exercising that power. The Hunter Biden laptop story, in which party operatives shanghaied 51 former high U.S. government intelligence and security officials to sign a letter that all but declared the laptop to be a fake, and part of a Russian disinformation plot—when most of those officials had very strong reasons to know or believe that the laptop and its contents were real—showed how the system worked. That letter was then used as the basis for restricting and banning factual reports about the laptop and its contents from digital platforms, with the implication that allowing readers to access those reports might be the basis for a future accusation of a crime. None of this censorship was official, of course: Trump was in the White House, not Obama or Biden. What that demonstrated was that the real power, including the power to control functions of the state, lay elsewhere.

Even more unusual, and alarming, was what followed Trump’s defeat in 2020. With the Democrats back in power, the new messaging apparatus could now formally include not just social and institutional pressure but the enforcement arms of the federal bureaucracy, from the Justice Department to the FBI to the SEC. As the machine ramped up, censoring dissenting opinions on everything from COVID, to DEI programs, to police conduct, to the prevalence and the effects of hormone therapies and surgeries on youth, large numbers of people began feeling pressured by an external force that they couldn’t always name; even greater numbers of people fell silent. In effect, large-scale changes in American mores and behavior were being legislated outside the familiar institutions and processes of representative democracy, through top-down social pressure machinery backed in many cases by the threat of law enforcement or federal action, in what soon became known as a “whole of society” effort.

At every turn over the next four years, it was like a fever was spreading, and no one was immune. Spouses, children, colleagues, and supervisors at work began reciting, with the force of true believers, slogans they had only learned last week, and that they were very often powerless to provide the slightest real-world evidence for. These sudden, sometimes overnight, appearances of beliefs, phrases, tics, looked a lot like the mass social contagions of the 1950s—one episode after another of rapid-onset political enlightenment replacing the appearance of dance crazes or Hula-Hoops.

During the Trump years, Obama used the tools of the digital age to craft an entirely new type of power center for himself, one that revolved around his unique position as the titular, though pointedly never-named, head of a Democratic Party that he succeeded in refashioning in his own image.

Just as in those commercially fed crazes, there was nothing accidental, mystical or organic about these new thought-viruses. Catchphrases like “defund the police,” “structural racism,” “white privilege,” “children don’t belong in cages,” “assigned gender” or “stop the genocide in Gaza” would emerge and marinate in meme-generating pools like the academy or activist organizations, and then jump the fence—or be fed—into niche groups and threads on Twitter or Reddit. If they gained traction in those spaces, they would be adopted by constituencies and players higher up in the Democratic Party hierarchy, who used their control of larger messaging verticals on social media platforms to advance or suppress stories around these topics and phrases, and who would then treat these formerly fringe positions as public markers for what all “decent people” must universally believe; those who objected or stood in the way were portrayed as troglodytes and bigots. From there, causes could be messaged into reality by state and federal bureaucrats, NGOs, and large corporations, who flew banners, put signs on their bathrooms, gave new days off from work, and brought in freshly minted consultants to provide “trainings” for workers—all without any kind of formal legislative process or vote or backing by any significant number of voters.

What mattered here was no longer Lippmann’s version of “public opinion,” rooted in the mass audiences of radio and later television, which was assumed to correlate to the current or future preferences of large numbers of voters—thereby assuring, on a metaphoric level at least, the continuation of 19th-century ideas of American democracy, with its deliberate balance of popular and representational elements in turn mirroring the thrust of the Founders’ design. Rather, the newly minted digital variant of “public opinion” was rooted in the algorithms that determine how fads spread on social media, in which mass multiplied by speed equals momentum—speed being the key variable. The result was a fast-moving mirror world that necessarily privileges the opinions and beliefs of the self-appointed vanguard who control the machinery, and could therefore generate the velocity required to change the appearance of “what people believe” overnight.

The unspoken agreements that obscured the way this social messaging apparatus worked—including Obama’s role in directing the entire system from above—and how it came to supplant the normal relationships between public opinion and legislative process that generations of Americans had learned from their 20th-century poli-sci textbooks, made it easy to dismiss anyone who suggested that Joe Biden was visibly senile; that the American system of government, including its constitutional protections for individual liberties and its historical system of checks and balances, was going off the rails; that there was something visibly unhealthy about the merger of monopoly tech companies and national security agencies with the press that threatened the ability of Americans to speak and think freely; or that America’s large cultural systems, from education, to science and medicine, to the production of movies and books, were all visibly failing, as they fell under the control of this new apparatus. Millions of Americans began feeling increasingly exhausted by the effort involved in maintaining parallel thought-worlds in which they expressed degrees of fealty to the new order in the hope of keeping their jobs and avoiding being singled out for ostracism and punishment, while at the same time being privately baffled or aghast by the absence of any persuasive logic behind the changes they saw—from the breakdown of law and order in major cities, to the fentanyl epidemic, to the surge of perhaps 20 million unvetted illegal immigrants across the U.S. border, to widespread gender dysphoria among teenage girls, to sudden and shocking declines in public health, life expectancy, and birth rates.

Until the fever broke. Today, Donald Trump is victorious, and Obama is the loser.

RTWT — This one’s a must-read essay.

20 Aug 2015

H.P. Lovecraft by Lee Moyer.

Philip Eil, in the Atlantic, contemplates with unease the posthumous rise to fame and pop culture ascendancy of the visionary horror pulp writer H.P. Lovecraft.

Lovecraft, you see, was not just a pulp writer. He was a passionate, nearly hydrophobic racist and anti-Semite, whose letters are absolutely filled with expressions of distaste for the presence, appearance, physiognomy, and even the odor, of Jews, Negroes, Asians, and persons of Southern European origin. The sight (and the smell), when encountered on city streets, of the result of 1900-era mass immigration could make the Mayflower-descended Lovecraft literally physically ill.

Hence, the dilemma troubling Mr. Eil: today’s American establishment culture faithfully worships at the altar of fame and success, but it simultaneously wants to cast out and obliterate anyone or anything incompatible with its own fanatically egalitarian ideology. Some pretty serious chin-stroking is in order here.

[N]o tale of posthumous success is quite as spectacular as that of Howard Phillips Lovecraft, the “cosmic horror†writer who died in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1937 at the age of 46. The circumstances of Lovecraft’s final years were as bleak as anyone’s. He ate expired canned food and wrote to a friend, “I was never closer to the bread-line.†He never saw his stories collectively published in book form, and, before succumbing to intestinal cancer, he wrote, “I have no illusions concerning the precarious status of my tales, and do not expect to become a serious competitor of my favorite weird authors.†Among the last words the author uttered were, “Sometimes the pain is unbearable.†His obituary in the Providence Evening Bulletin was “full of errors large and small,†according to his biographer.

Nowadays, it’s hard to imagine Lovecraft faced such poverty and obscurity, when regions of Pluto are named for Lovecraftian monsters, the World Fantasy Award trophy bears his likeness, his work appears in the Library of America, the New York Review of Books calls him “The King of Weird,†and his face is printed on everything from beer cans to baby books to thong underwear. The author hasn’t just escaped anonymity; he’s reached the highest levels of critical and cultural success. His is perhaps the craziest literary afterlife this country has ever seen. …

My feelings on Lovecraft—as a bibliophile, a lover of Providence history, a Jew, a fan of his writing, a teacher who assigns his stories—are complicated. At their best, his tales achieve a visceral eeriness, or fling the reader’s imagination to the furthest depths of outer space. Once you develop a taste for his maximalist style, these stories become addictive. But my admiration is always coupled with the knowledge that Lovecraft would have found my Jewish heritage repugnant, and that he saw our shared hometown as a haven from the waves of immigrants he saw as infecting other cities. (“America has lost New York to the mongrels, but the sun shines just as brightly over Providence,†he wrote to a friend in 1926.)

I haven’t made peace with this tension, and I’m not sure I ever will. But I have decided that perhaps he’s the literary icon our country deserves. The stories he conjured, in many ways, say as much about his bigotry as they do his genius. Or, as Moore writes, “Coded in an alphabet of monsters, Lovecraft’s writings offer a potential key to understanding our current dilemma.â€

03 Aug 2015

A recently much-praised article by Helen Andrews, in the Summer issue of University Bookman, designates Left Coast lesbian literateur Terry Castle as “the Anti-[Camille]-Paglia.” I was not familiar with La Castle, but a link in the essay led me to this affectionate (and irritated) posthumous tribute to a mutual friend: the late Susan Sontag.

Enfin – la fin. I heard she was dead as Bev and I were driving back from my mother’s after Christmas. Blakey called on the cellphone from Chicago to say she had just read about it online; it would be on the front page of the New York Times the next day. It was, but news of the Asian tsunami crowded it out. (The catty thing to say here would be that Sontag would have been annoyed at being upstaged; the honest thing to say is that she wouldn’t have been.) The Times did another piece a few days later – a somewhat dreary set of passages from her books, entitled: ‘No Hard Books, or Easy Deaths’. (An odd title: her death wasn’t easy, but she was all about hard books.) And in the weeks since, the New Yorker, New York Review of Books and various other highbrow mags have kicked in with the predictable tributes.

But I’ve had the feeling the real reckoning has yet to begin. The reaction, to my mind, has been a bit perfunctory and stilted. A good part of her characteristic ‘effect’ – what one might call her novelistic charm – has not yet been put into words. Among other things, Sontag was a great comic character: Dickens or Flaubert or James would have had a field day with her. The carefully cultivated moral seriousness – strenuousness might be a better word – co-existed with a fantastical, Mrs Jellyby-like absurdity. Sontag’s complicated and charismatic sexuality was part of this comic side of her life. The high-mindedness, the high-handedness, commingled with a love of gossip, drollery and seductive acting out – and, when she was in a benign and unthreatened mood, a fair amount of ironic self-knowledge. …

At the moment it’s hard to imagine anyone ever possessing the same symbolic weight, the same adamantine hardness, or having the same casual imperial hold over such a large chunk of my brain. I am starting to think in any case that she was part of a certain neural development that, purely physiologically speaking, can never be repeated. All those years ago one evolved a hallucination about what mental life could be and she was it. She’s still in there, enfolded somehow in the deepest layers of the grey matter. Yes: Susan Sontag was sibylline and hokey and often a great bore. She was a troubled and brilliant American. …

Being not a lesbian and of a generation younger than herself, my own relationship with Susan Sontag was both slighter and less vexed.

Sontag was rather an adolescent intellectual idol of mine. Her early critical essays (of the Against Interpretation period) delivered to the provincial reader like myself up-to-the-minute reports (for good or ill) of life at the Parisian and Manhattan cutting edges of contemporary culture.

I was, from my teenage years, an opponent of Modernism and Leftism, and Sontag was the head cheerleader of both. I usually despised the entire worldview and being of representatives of the establishment pseudo-intelligentsia. I typically read the Times Book Review and Arts Section and the New Yorker with a bitter sneer curling my lip. But Sontag was a different case. She was on the wrong side, but she was obviously a genuine, and absolutely brilliant, intellectual.

I’d always had a hankering to meet Susan Sontag, and finally by one of the most preposterous of circumstances I did. Karen and I were back in Pennsylvania one weekend fishing my major boyhood trout stream, Fishing Creek in Columbia County. As we drove through Bloomsburg, we found posted everywhere announcements of a film screening and lecture at Bloomsburg State U. (not much earlier: Bloomsburg State Teachers’ College) by Susan Sontag herself.

Sontag was a bit startled when an adult couple, reeking of sunscreen and insect repellent and fresh out of waders, arrived to join the throng of English professors and admiring undergraduates. We immediately secured her attention, introduced ourselves, and rather monopolized the event by interviewing Sontag ourselves. We naturally inquired how it came to be that an internationally-renowned cultural demi-goddess could be found speaking at, er.. ahem…, one of the less illustrious institutions of higher education rather than atop Olympus, and Sontag grinned ruefully and explained that she paid her basic living expenses by doing twelve (outrageously highly-paid) appearances at inevitably twelve of the remotest and most rinky-dink schools in America. On the whole, she opined, it was a pretty easy way to make a living. Just horribly boring, until life-of-the-party Yalies like Karen and myself happened to turn up.

I think we might well have kidnapped Susan and carried her home to Connecticut to drink, smoke, and argue music and films indefinitely, but she was escorted by her son, David Rieff, who took the responsibility for keeping Susan on track. In the end, Susan et fils went off to pay their dues by giving some attention to the Blooomsburg college’s factotums, and bidding her a fond farewell, Karen and I went off to catch the evening hatch.

It was a few months later that I next ran into Sontag. I had gone to the Bleeker Street Cinena to catch an 11 AM showing of Mizoguchi’s “Ugetsu” (1954). A familiar figure was standing in the ticket line, and (not wanting to announce her identity to the crowd) I merely walked over and said: “I believe that you are the lady I met recently in Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania.” Sontag recognized me, cracked up, and we wound up sitting together through the film. Sontag and I had, history demonstrates, a similar taste in the cinema, so we ran into each other repeatedly in theater lobbies. If Sontag was in company, we would wave and smile, but if she was alone, we would sit together.

The cultural life of New York City typically runs to one terribly-important event per season. Back in the period in which I was living or working in New York, Karen and I would reliably be attending that event and, of course, so would Susan Sontag. We ran into Susan at a number of these, and got to sit with her a few times. At the Radio City Music Hall showing of the rediscovered and restored print of Abel Gance’s “Napoleon” (1927), Sontag somehow arranged to have us placed beside her and her companion, the aged, but extremely witty, Lillian Gish. Cinemaphiles watching a silent movie can have an especially good time, since it is perfectly possible to chat continuously and to exchange critical or humorous observations throughout the viewing without actually spoiling the movie.

Sontag also introduced us to Stephen Spielberg and George Lucas at the Lincoln Center showing of Syberberg’s “Parzifal” (1982).

My own experience of Susan Sontag was clearly a good deal different from Terry Castle’s. I found that, if one could talk to Susan Sontag on her own level and if one could entertain and amuse her, one’s personal lack of celebrity status was not really a problem. Of course, neither Karen nor I were ever involved with her romantically, and our entire relationship was based merely upon happenstance runnings into one another. We never made any effort to enlarge our acquaintanceship and we never made any demands upon her.

I did once make a serious effort to persuade Susan Sontag to come over to the Conservative political camp (unsuccessfully), but that is another story.

04 Feb 2015

Phys Org:

A new cultural psychology study has found that psychological differences between the people of northern and southern China mirror the differences between community-oriented East Asia and the more individualistic Western world – and the differences seem to have come about because southern China has grown rice for thousands of years, whereas the north has grown wheat.

“It’s easy to think of China as a single culture, but we found that China has very distinct northern and southern psychological cultures and that southern China’s history of rice farming can explain why people in southern China are more interdependent than people in the wheat-growing north,” said Thomas Talhelm, a University of Virginia Ph.D. student in cultural psychology and the study’s lead author. He calls it the “rice theory.”

The findings appear in the May 9 issue of the journal Science.

Talhelm and his co-authors at universities in China and Michigan propose that the methods of cooperative rice farming – common to southern China for generations – make the culture in that region interdependent, while people in the wheat-growing north are more individualistic, a reflection of the independent form of farming practiced there over hundreds of years.

“The data suggests that legacies of farming are continuing to affect people in the modern world,” Talhelm said. “It has resulted in two distinct cultural psychologies that mirror the differences between East Asia and the West.”

Read the whole thing.

Via Fred Lapides.

26 Jul 2014

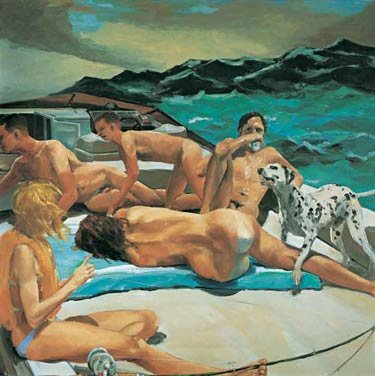

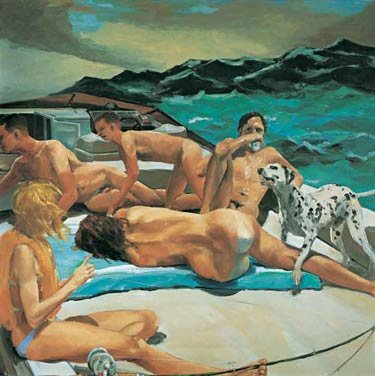

Eric Fischl, The Old Man’s Boat and the Old Man’s Dog, 1982. –Our time’s version of The Raft of the Medusa.

Fred Reed is not impressed with what egalitarian progressive modernism has wrought.

The bleakness of American culture leads one to despair. Subtract technology and nothing is left. Music? Classical composition is dead. The symphony orchestras hold on by their teeth. Opera is unheard and almost unheard of. Book sales drop, and those that sell are mostly trash. Poetry is dead, Shakespeare a comic shorthand for ridiculous irrelevant pedantry.

Talented painters abound, but the nation has no interest in them. Sculpture means curious blobs and shapes said to be art and chosen by suburban arts committees. Theater? How many people have seen a play recently other than a high-school production?

In all the things that once marked civilization, the United States has become a desert, a waste of self-satisfied, pampered, arrogantly ignorant sidewalk peasants. This is curious, since anything the cultivated might want awaits on the web. One may think of Amazon as an automated fifth-century monastery, saving things of worth for an awakening centuries hence.

Read the whole thing.

Hat tip to Vanderleun.

22 Aug 2012

The left dominates the media, the universities, Hollywood, the arts, all the engines and apparatuses of communication and creation of culture. Jonathan Chait, in New York magazine, freely admits what everybody knows, and openly gloats.

You don’t have to be an especially devoted consumer of film or television (I’m not) to detect a pervasive, if not total, liberalism. Americans for Responsible Television and Christian Leaders for Responsible Television would be flipping out over the modern family in Modern Family, not to mention the girls of Girls and the gays of Glee, except that those groups went defunct long ago. The liberal analysis of the economic crisis—that unregulated finance took wild gambles—has been widely reflected, even blatantly so, in movies like Margin Call, Too Big to Fail, and the Wall Street sequel. The conservative view that all blame lies with regulations forcing banks to lend to poor people has not, except perhaps in the amateur-hour production of Atlas Shrugged. The muscular Rambo patriotism that briefly surged in the eighties, and seemed poised to return after 9/11, has disappeared. In its place we have series like Homeland, which probes the moral complexities of a terrorist’s worldview, and action stars like Jason Bourne, whose enemies are not just foreign baddies but also paranoid Dick Cheney figures. The conservative denial of climate change, and the low opinion of environmentalism that accompanies it, stands in contrast to cautionary end-times tales like Ice Age 2: The Meltdown and the tree-hugging mysticism of Avatar. The decade has also seen a revival of political films and shows, from the Aaron Sorkin oeuvre through Veep and The Campaign, both of which cast oilmen as the heavies. Even The Muppets features an evil oil driller stereotypically named “Tex Richman.â€

In short, the world of popular culture increasingly reflects a shared reality in which the Republican Party is either absent or anathema. That shared reality is the cultural assumptions, in particular, of the younger voters whose support has become the bedrock of the Democratic Party. …

[The] capacity to mold the moral premises of large segments of the public, and especially the youngest and most impressionable elements, may or may not be unfair. What it is undoubtedly is a source of cultural (and hence political) power. Liberals like to believe that our strength derives solely from the natural concordance of the people, that we represent what most Americans believe, or would believe if not for the distorting rightward pull of Fox News and the Koch brothers and the rest. Conservatives surely do benefit from these outposts of power, and most would rather indulge their own populist fantasies than admit it. But they do have a point about one thing: We liberals owe not a small measure of our success to the propaganda campaign of a tiny, disproportionately influential cultural elite.

01 Mar 2011

Scrooge McDuck and his nephew Donald were responsible for some pretty impressive cultural contributions.

Hat tip to Jose Guardia.

————————————-

According to Jay Black, Nathan Fillion is television’s Martin Luther.

————————————–

When the alien invaders arrive…

16 Nov 2010

Walter Kirn, in his autobiographical Lost in the Meritocracy: The Undereducation of an Overachiever , describes the post-modern English major experience and explains the nature of the conversion process to full membership in the contemporary elite educated community of fashion. , describes the post-modern English major experience and explains the nature of the conversion process to full membership in the contemporary elite educated community of fashion.

[A] suffocating sensation often came over me whenever I opened Deconstruction and Criticism , a collection of essays by leading theory people that I spotted everywhere that year and knew to be one of the richest sources around for words that could turn a modest midterm essay into an A-plus tour de force HerÄ™ is a sentence (or what I took to be one because it ended with a period) from the contribution by the Frenchman Jacques Derrida, the volume’s most prestigious name: “He speaks his mother tongue as the language of the other and deprives himself of all reappropriation, all specularization in it.” On the same page I encountered the windpipe-blocking “heteronomous” and “invagination.” When I turned the page I came across— stuck in a footnote—”unreadability.” , a collection of essays by leading theory people that I spotted everywhere that year and knew to be one of the richest sources around for words that could turn a modest midterm essay into an A-plus tour de force HerÄ™ is a sentence (or what I took to be one because it ended with a period) from the contribution by the Frenchman Jacques Derrida, the volume’s most prestigious name: “He speaks his mother tongue as the language of the other and deprives himself of all reappropriation, all specularization in it.” On the same page I encountered the windpipe-blocking “heteronomous” and “invagination.” When I turned the page I came across— stuck in a footnote—”unreadability.”

That word I understood, of course.

But real understanding was rare with theory. It couldn’t be depended on at all. Boldness of execution was what scored points. With one of my professors, a snappy “heuristic” usually did the trick. With another, the charm was a casual “praxis.” Even when a poem or story fundamentally escaped me, I found that I could save face with terminology, as when I referred to T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land as “semiotically unstable.” By this I meant “hard.” All the theory words meant “hard” to me, from “hermeneutical” to “gestural.” Once in a while I’d look one up and see that it had a more specific meaning, but later—some-times only minutes later—the definition would catch a sort of breeze, float away like a dandelion seed, and the word would go back to meaning “hard.”

The need to finesse my ignorance through such trickery-” honorable trickery to my mind, but not to other minds, perhaps—left me feeling hollow and vaguely haunted. Seeking security in numbers, I sought out the company of other frauds. We recognized one another instantly. We toted around books by Roland Barthes, Hans-Georg Gadamer, and Walter Benjamin. We spoke of “playfulness” and “textuality” and concluded before we’d read even a hundredth of it that the Western canon was “illegitimate,” a veiled expression of powerful group interests that it was our duty to subvert. In our rush to adopt the latest attitudes and please the younger and hipper of our instructors—the ones who drank with us at the Nassau Street bars and played the Clash on the tape decks of their Toyotas as their hands crept up our pants and skirts—we skipped straight from ignorance to revisionism, deconstructing a body of literary knowledge that we’d never constructed in the first place.

For true believers, the goal of theory seemed to be the lifting of a great weight from the shoulders of civilization. This weight was the illusion that it was civilized. The weight had been set there by a rangÄ™ of perpetrators—members of certain favored races, males, property owners, the church, the literate, natives of the northern hemisphere—who, when taken together, it seemed to me, represented a considerable portion of everyone who had ever lived. Then again, of course I’d think that way. Of course I’d be cynical. I was one of them.

So why didn’t I feel like one of them, particularly just then? why did I, a member of the classes that had supposedly placed e weight on others and was now attempting to redress this crime, feel so crushingly weighed down myself?

I wasn’t one of theory’s true believers. I was a confused young opportunist trying to turn his confusion to his advantage by sucking up to scholars of confusion. The literary works they prized —the ones best suited to their project of refining and hallowing confusion—were, quite naturally, knotty and oblique The poems of Wallace Stevens, for example. My classmates and I found them maddeningly elusive, like collections of backward answers to hidden riddles, but luckily we could say “recursive” by then. We could say “incommensurable.” Both words meant “hard.”

I grew to suspect that certain professors were on to us, and I wondered if they, too, were fakes. In classroom discussions, and even when grading essays, they seemed to favor us over the hard workers, whose patient, sedentary study habits, and sense that confusion was something to be avoided rather than celebrated, appeared unsuited to the new attitude of antic postmodernism that I had mastered almost without effort. To thinkers of this school, great literature was an incoherent con, and I—a born con man who knew little about great literature—had every reason to agree with them. In the land of nonreadability, the nonreader was king, it seemed. Long live the king.

This lucky convergence of academic fashion and my illiteracy emboldened me socially. It convinced me I had a place at Princeton after all. I hadn’t chosen it, exactly, but I’d be foolish not to occupy it. Otherwise I’d be alone.

Finally, without reservations or regrets, I settled into the ranks of Princeton’s Joy Division—my name for the crowd of moody avant-gardists who hung around the smaller campus theaters discussing, enjoying, and dramatizing confusion. One of their productions, which I assisted with, required the audience to contemplate a stage decorated with nothing but potted plants. Plants and Waiters, it was called. My friends and I stood snickering in the wings making bets on how long it would take people to leave. They, the “waiters,” proved true to form. They fidgeted but they didn’t flee. Hilarious.

And, for me, profoundly enlightening. Who knew that serious art could be like this? Who would have guessed that the essence of high culture would turn out to be teasing the poor saps that still believed in it? Certainly no one back in Minnesota. Well, the joke was on them, and I was in on it. I could never go back there now. It bothered me that I’d ever even lived there, knowing that people here on the great coast (people like me— the new, emerging me) had been laughing at us all along. But what troubled me more was the dawning realization that had I not reached Princeton, I might never have discovered this; I might have stayed a rube forever. This idea transformed my basic loyalties. I decided that it was time to leave behind the sort of folks whom I’d been raised around and stand—for better or for worse—with the characters who’d clued me in.

30 Sep 2010

Evert Cilliers aka Adam Ash discusses the kind of art produced today for readers of the New Yorker, for the believing-itself-to-be-hip, pseudo-educated urban community of fashion, things like the films of Woody Allen and the novels of Don DeLillo.

There is a certain kind of art made here in America for a lofty but banal purpose: to enliven the contemporary educated mind.

You know: the mind of you and me, dear 3QD reader — the NPR listener, the New Yorker reader, the English major, the filmgoer who laps up subtitles, the gallery-goer who can tell a Koons from a Hirst.

This art is superior to the cascading pile of blockbuster kitsch-dreck-crap that passes for pop culture, but only superior by a few pips.

This art sure ain’t Picasso, or Joyce, or Rossellini, or the Beatles, or even Sondheim. It’s more Woody Allen than Ingmar Bergman, more Joyce Carol Oates than James Joyce, more Jeff Koons than Duchamp, more Arcade Fire than the Beatles.

It does not expand the borders of art or wreck the tyranny of the possible or enlarge our hungry little minds.

It is art of the day to inform the conversation of the day by the people of the day who need to be reassured that their taste is a little more elevated than that of the woman on the subway reading Nora Roberts.

For want of a better label, here’s a suggested honorific for this kind of art:

Urban Intellectual Fodder.

Neither original nor path-breaking, this art is derivative hommage; postmodern commentary around the edges of art.

It is art born of attitude, not passion. It is art that postures but doesn’t grip. It is art created by those who are more passionate about a career in art than about art itself. …

What distinguishes this art from actual art?

Primarily, this is art that thinks about art. Art of the intellect, not the heart. Art done to bring us the smart, not the art.

The artists of Urban Intellectual Fodder act like art critics doing art — they’re better about their art than with it, better on their art than in it. Their art is done to show their smarts, and that’s primarily what one gets from their art.

Smart art: in America, the land of anti-intellectualism, it’s perhaps inevitable that our art should devolve into a screech against the national celebration of the dumb.

Unfortunately, this art does the smart thing to the detriment of the other things that art can do. It does the soothing, lulling thing, because it is art to make the viewer feel smart. The audience I’m talking about wants only that from art: to be made to feel smart. So they get their art of the brain, for the brain and by the brain. Art that panders with its braininess.

Urban Intellectual Fodder is the prozac of the American intelligentsia.

It’s studiedly smart; it’s properly elliptical; it’s quite self-aware and often very meta; it is extensively footnoted, either actually or mentally; its distance from its material is either ironically remote or uncomfortably close-up; it is intensely minimal or wordy or effects-ridden, in either a refined or extravagant way; it specializes in conceits, and sometimes its conceit is to be devoid of one; and it makes its small points, and sometimes its big obvious ones, in either a very guarded or rather grandiosely ironical way.

Critic James Wood coined a name for it: “hysterical realism.†Dale Peck had a name for it, too: “recherche postmodernism.â€

Hat tip to Karen L. Myers.

17 May 2009

Fjordman observes that the Chinese have a special enthusiasm for Western classical music while Muslims commonly care little for Western music or art. When Muslims look for inspiration to the West, their admiration is focused on weapons of mass destruction, the authoritarian state, socialism, and militaristic nationalism, in other words: fascism. The leading political movement in the post colonial Islamic world has been Ba’athism, a political movement specifically modeled on German National Socialism.

Despotism comes quite natural to Islamic culture. When confronted with the European tradition, many Muslims freely prefer Adolf Hitler to Rembrandt, Michelangelo or Beethoven. Westerners don’t force them to study Mein Kampf more passionately than Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa or Goethe’s Faust; they choose to do so themselves. Millions of (non-Muslim) Asians now study Mozart’s piano pieces. Muslims, on the other hand, like Mr. Hitler more, although he represents one of the most evil ideologies that have ever existed in Europe. The fact that they usually like the Austrian Mr. Hitler more than the Austrian Mr. Mozart speaks volumes about their culture. Koreans, Japanese, Chinese and Middle Eastern Muslims have been confronted with the same body of ideas, yet choose to appropriate radically different elements from it, based upon what is compatible with their own culture.

07 Jan 2009

Andrew Breitbart’s new group blog forum for film industry conservatives launched yesterday. First day’s posters include Andrew Klavan, John Nolte, Orson Bean, Melanie Graham, and “Veritas Obviam” (who obviously does not want to lose his career). Perhaps this one will fill the badly needed role of main conservative outlet for commentary on new movie releases and the ideological excesses of the establishment film industry.

17 Jan 2007

Marco Evaristti, edgy Chilean artist, at his latest exhibit in Santiago has served up meatballs made from his own fat.

Foxnews.com:

“Ladies and gentleman, bon appetit and may god bless,” said Marco Evaristti, a glass in his hand, to his dining companions seated last Thursday night around a table in Santiago’s Animal Gallery.

On the plates in front of them was a serving of agnolotti pasta and in the middle a meatball made with oil Evaristti removed from his body in a liposuction procedure last year.

“The question of whether or not to eat human flesh is more important than the result,” he said, explaining the point of his creation.

“You are not a cannibal if you eat art,” he added.

Evaristti produced 48 meatballs with his own fat, some of which would be canned and sold for $US4000 dollars for 10.

A veteran at shock-art, in an earlier work Evaristti invited people to kill fish by pressing the button on a blender the fish were held in.

In April 2004 he dyed an enormous iceberg in Greenland with red paint.

Santiago Times:

Six years ago, artist Marco Evaristti scandalized the Chilean art world when he displayed live fish in working blenders. The opening of his new exhibit at the Animal Gallery in Vitacura is likely to cause just as much sensation, hype and criticism when visitors are invited to eat meatballs made with Evaristti’s own fat.

The Chilean-Danish artist, who underwent liposuction for the work, describes it as a criticism of the plastic surgery market. The meatballs are canned and available for purchase; two cans have already been sold to collectors for US$23,200 each. Evaristti claims that the meatballs are not only delicious, but contain less fat than supermarket meatballs.

President Bachelet and poet Nicanor Parra were invited to enjoy the dish at the opening. Neither has given a response so far. The artist assured that he, if no one else, would enjoy the meal.

Another controversial piece consists of six fake faeces covered in gold taken from the teeth of Jewish holocaust victims…

Exhibit details:

GalerÃÂa Animal

Alonso de Cordova 3105

Vitacura

M-F 10:00-8:00

Saturday 10:30-2:00

Until January 27th.

One couldn’t make this stuff up.

/div>

Feeds

|