Category Archive 'Modernism'

22 Apr 2023

For two hundred years we have sawed and sawed and sawed at the branch we are sitting on. And in the end much more suddenly than anyone has foreseen, our efforts were rewarded, and down we came. But unfortunately there had been a little mistake. The thing at the bottom was not a bed of roses after all, it was a cesspool full of barbed wire.

–George Orwell, 1940

23 Jul 2018

Irving Babbitt, 1865-1933.

Amanda Reichenbach, a recent graduate of Yale, has an excellent essay in National Review on the now-almost-forgotten humanist Irving Babbitt’s critique of Modernism.

Babbitt reacted against what he regarded as the twin evils of the modern era: Romanticism and utilitarian scientism. … Babbitt did not see them as opposed forces. Rather, they worked in concert to reduce humans — complex, multi-dimensional beings — to cardboard cutouts incapable of moral choice.

Babbitt’s fundamental view of the human condition was that the “higher will†waged a lifelong, internal “civil war in the cave†against the “lower will.†Modernity, he believed, tended to collapse the distinction between the two wills. That “man is naturally good and that it is by our institutions alone that men become wicked†is, he thought, the most dangerous belief, found in Rousseau’s Confessions. It replaces the true dualism of the “civil war in the cave†with dualism between man and society.

This individual who sees liberty in the ability to follow every whim — someone whom Deneen would call a liberal, and Babbitt a Romantic — is drawn to a sentimental libertinism in which indulgent emotion is elevated over the hard work of becoming a good person. The Romantic wishes to see destroyed any laws and customs that might prevent him from doing all that his heart desires.

When human passions are released, however, writes Babbitt, “what emerges in the real world is not the mythical will to brotherhood, but the ego and its fundamental will to power.†The will to power often presents itself in palatable ways, replacing traditional notions of virtue with what Babbitt calls “a sort of parody of Christian charity.†The Romantic is drawn not to humanism but to emotional humanitarianism. Believing himself to be blameless, the Romantic locates the source of society’s evils in everybody else. The Romantic humanitarian, Babbitt argues, will always go around pointing out the specks in his neighbors’ eyes while a plank burdens his own. Rousseau, the chief example of this tendency, wrote a 500-page book on how to raise and educate children, after leaving five of his own to a foundling hospital.

The Romantic soon discovers that a lack of restraint is a sure recipe for loneliness, though he has been promised emotional communion with his fellow beautiful souls. When he finds that his philosophy is based on Arcadian unreality, his disillusion leads him to “drift towards a naturalistic fatalism.†Babbitt argues that the rise of science and sociology teaches man that he is entirely a product of his circumstances and incapable of individual moral improvement. Here, too, the lines are not drawn between what is good and what is bad within each human, but between the individual and the society that conditions him. Given the twin influences of Romanticism and scientism, Babbitt feared, “man is in danger of being deprived of every last scrap and vestige of his humanity,†since he “becomes human only in so far as he exercises moral choice.â€

A must-read.

16 Jun 2017

Bad! Male shooting trap.

GunsAmerica makes it clear that entirely the wrong kind of people are on the International Olympic Committee.

The International Olympic Committee has dropped three men’s shooting events from the Tokyo 2020 lineup in an effort to make the games “more youthful, more urban†and more inclusive of women.

The Committee announced last Friday that men’s double trap, 50m rifle prone, and 50m pistol will be replaced by events in air rifle, trap, and air shooting, which will be open to competitors of any gender.

IOC President Thomas Bach said in a statement, “I am delighted that the Olympic Games in Tokyo will be more youthful, more urban and will include more women.â€

———————-

Evelyn Waugh’s Scott-King’s Modern Europe follows the declining career of a balding & corpulent classics teacher at Granchester, a fictional English public school. Granchester is “entirely respectable†but in need of a bit of modernizing, at least in the opinion of its pragmatic headmaster, who is attuned to consumer demands. The story ends with a poignant conversation between Scott-King and the headmaster:

“You know,†[the headmaster] said, “we are starting this year with fifteen fewer classical specialists than we had last term?â€

“I thought that would be about the number.â€

“As you know I’m an old Greats man myself. I deplore it as much as you do. But what are we to do? Parents are not interested in producing the ‘complete man’ any more. They want to qualify their boys for jobs in the modern world. You can hardly blame them, can you?â€

“Oh yes,†said Scott-King. “I can and do.â€

“I always say you are a much more important man here than I am. One couldn’t conceive of Granchester without Scott-King. But has it ever occurred to you that a time may come when there will be no more classical boys at all?â€

“Oh yes. Often.â€

“What I was going to suggest was—I wonder if you will consider taking some other subject as well as the classics? History, for example, preferably economic history?â€

“No, headmaster.â€

“But, you know, there may be something of a crisis ahead.â€

“Yes, headmaster.â€

“Then what do you intend to do?â€

“If you approve, headmaster, I will stay as I am here as long as any boy wants to read the classics. [Emphasis added] I think it would be very wicked indeed to do anything to fit a boy for the modern world.â€

“It’s a short-sighted view, Scott-King.â€

“There, headmaster, with all respect, I differ from you profoundly. I think it the most long-sighted view it is possible to take.â€

29 Nov 2016

Hat tip to Vanderleun.

06 Oct 2016

Ryszard Lugutko, Professor of philosophy at the Jagellonian University in Cracow.

From The Demon in Democracy: Totalitarian Temptations in Free Societies by Ryszard Legutko.

Liberal and democratic thought had been, from the very beginning –- with few exceptions -– minimalist when it came to its image of the human being. The triumph of liberalism and democracy was supposed to be emancipatory also in the sense that man was to become free from excessive demands imposed on him by unrealistic metaphysics invented by an aristocratic culture in antiquity and the Middle Ages. In other words, an important part of the message of modernity was to legitimize a lowering of human aspirations. Aspiring to great goals was not ruled out in particular cases, but greatness was no longer inscribed in the essence of humanity. The main principle behind the minimalist perspective was equality: from the point of view of a liberal order one cannot prioritize human objectives. Only the means can be prioritized in terms of efficiency, provided this does not jeopardize the rules of peaceful cooperation. …

There were, as I’ve said, exceptions to this view –- few, but worth noting. Among the eighteenth century authors, Kant, who defended liberalism, set up high standards for humanity; in the 19th century, John Stuart Mill and T.H. Green had similar intentions. The last two aptly perceived the danger of mediocrity that the democratic rule was inconspicuously imposing on modern societies. They both believed –- differences notwithstanding -– that some form of liberalism, or rather, a philosophy of liberty, was a possible remedy to the creeping disease of mediocrity. Mill remained under the partial, albeit indirect influence of German Romanticism, and thus attributed a particular role to great, creative individuals whose exceptionality or even eccentricity could –- in a free environment -– pull men out of a democratic slumber.

But these ideas did not find followers, and liberal democratic thought and practice increasingly fell into the logic of minimalism. Lowering the requirements is a process that has no end. Once people become used to disqualifying certain standards as too high, impractical, or unnecessary, it is only a matter of time before natural inertia takes its course and even the new lowered standards are deemed unacceptable. One can look at the history of liberal democracy as a gradual sliding down from the high to the low, from the refined to the coarse. Quite often a step down as been welcomed as refreshing, natural, and healthy, and indeed it sometimes was. But whatever the merits of this process of simplification, it too often brought vulgarity to language, behavior, education, and moral rules. The growing vulgarity of form was particularly striking, especially in the last decades, moving away from sophistication and decorum. A liberal-democratic man refused to learn these artificial and awkward arrangements, the usefulness of which seemed to him at first doubtful, and soon -– null. He felt he had no time for them, apparently believing that their absence would make life easier and more enjoyable. In their place he establish new criteria: use, practicality, usefulness, pleasure, convenience, and immediate gratification, the combination of which turned out to be a deadly weapon against the old social forms. The old customs crumbled, and so did rules of propriety, a sense of decorum, a respect for hierarchy.

Read the rest of this entry »

17 Aug 2014

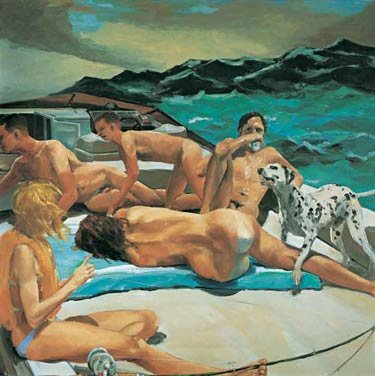

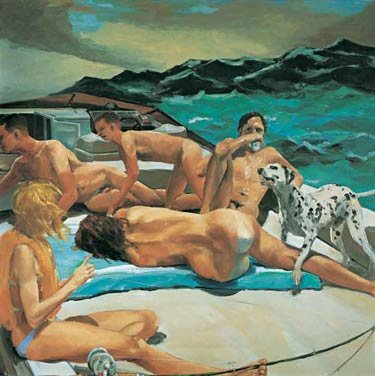

Eric Fischl, The Old Man’s Boat and the Old Man’s Dog, 1982. –Our time’s version of The Raft of the Medusa.

Mark Lila, back in June, published an important essay on contemporary ideology in the New Republic, which I would say misidentifies the contemporary ideology of secular egalitarianism as “Libertarianism.”

The social liberalization that began in a few Western countries in the 1960s is meeting less resistance among educated urban elites nearly everywhere, and a new cultural outlook, or at least questioning, has emerged. This outlook treats as axiomatic the primacy of individual self-determination over traditional social ties, indifference in matters of religion and sex, and the a priori obligation to tolerate others. Of course there have also been powerful reactions against this outlook, even in the West. But outside the Islamic world, where theological principles still have authority, there are fewer and fewer objections that persuade people who have no such principles. The recent, and astonishingly rapid, acceptance of homosexuality and even gay marriage in so many Western countries—a historically unprecedented transformation of traditional morality and customs—says more about our time than anything else.

It tells us that this is a libertarian age. That is not because democracy is on the march (it is regressing in many places), or because the bounty of the free market has reached everyone (we have a new class of paupers), or because we are now all free to do as we wish (since wishes inevitably conflict). No, ours is a libertarian age by default: whatever ideas or beliefs or feelings muted the demand for individual autonomy in the past have atrophied. There were no public debates on this and no votes were taken. Since the cold war ended we have simply found ourselves in a world in which every advance of the principle of freedom in one sphere advances it in the others, whether we wish it to or not. The only freedom we are losing is the freedom to choose our freedoms.

Not everyone is happy about this. The left, especially in Europe and Latin America, wants to limit economic autonomy for the public good. Yet they reject out of hand legal limits to individual autonomy in other spheres, such as surveillance and censorship of the Internet, which might also serve the public good. They want an uncontrolled cyberspace in a controlled economy—a technological and sociological impossibility. Those on the right, whether in China, the United States, or elsewhere, would like the inverse: a permissive economy with a restrictive culture, which is equally impossible in the long run. We find ourselves like the man on the speeding train who tried to stop it by pulling on the seat in front of him.

Yet our libertarianism is not an ideology in the old sense. It is a dogma. The distinction between ideology and dogma is worth bearing in mind. Ideology tries to master the historical forces shaping society by first understanding them. The grand ideologies of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries did just that, and much too well; since they were intellectually “totalizing,†they countenanced political totalitarianism. Our libertarianism operates differently: it is supremely dogmatic, and like every dogma it sanctions ignorance about the world, and therefore blinds adherents to its effects in that world. It begins with basic liberal principles—the sanctity of the individual, the priority of freedom, distrust of public authority, tolerance—and advances no further. It has no taste for reality, no curiosity about how we got here or where we are going. There is no libertarian sociology (an oxymoron) or psychology or philosophy of history. Nor, strictly speaking, is there a libertarian political theory, since it has no interest in institutions and has nothing to say about the necessary, and productive, tension between individual and collective purposes. It is not liberal in a sense that Montesquieu, the American Framers, Tocqueville, or Mill would have recognized. They would have seen it as a creed little different from Luther’s sola fide: give individuals maximum freedom in every aspect of their lives and all will be well. And if not, then pereat mundus.

Libertarianism’s dogmatic simplicity explains why people who otherwise share little can subscribe to it: small-government fundamentalists on the American right, anarchists on the European and Latin American left, democratization prophets, civil liberties absolutists, human rights crusaders, neoliberal growth evangelists, rogue hackers, gun fanatics, porn manufacturers, and Chicago School economists the world over. The dogma that unites them is implicit and does not require explication; it is a mentality, a mood, a presumption—what used to be called, non-pejoratively, a prejudice. Maintaining an ideology requires work because political developments always threaten its plausibility. Theories must be tweaked, revisions must be revised. Since ideology makes a claim about the way the world actually works, it invites and resists refutation. A dogma, by contrast, does not. That is why our libertarian age is an illegible age.

A must read.

26 Jul 2014

Eric Fischl, The Old Man’s Boat and the Old Man’s Dog, 1982. –Our time’s version of The Raft of the Medusa.

Fred Reed is not impressed with what egalitarian progressive modernism has wrought.

The bleakness of American culture leads one to despair. Subtract technology and nothing is left. Music? Classical composition is dead. The symphony orchestras hold on by their teeth. Opera is unheard and almost unheard of. Book sales drop, and those that sell are mostly trash. Poetry is dead, Shakespeare a comic shorthand for ridiculous irrelevant pedantry.

Talented painters abound, but the nation has no interest in them. Sculpture means curious blobs and shapes said to be art and chosen by suburban arts committees. Theater? How many people have seen a play recently other than a high-school production?

In all the things that once marked civilization, the United States has become a desert, a waste of self-satisfied, pampered, arrogantly ignorant sidewalk peasants. This is curious, since anything the cultivated might want awaits on the web. One may think of Amazon as an automated fifth-century monastery, saving things of worth for an awakening centuries hence.

Read the whole thing.

Hat tip to Vanderleun.

28 Jun 2014

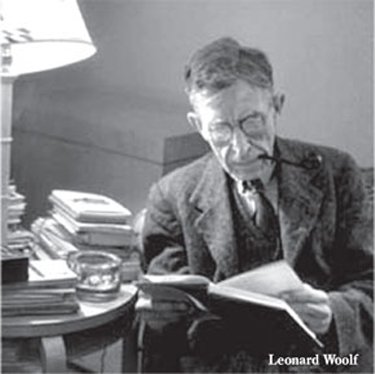

In his 2010 essay, “The Death of a Civil Servant,” fantasy novelist Lev Grossman finds the collision between Modernism and the Revulsion Against Modernism Expressed as Fantasy exemplified in the 1905 colonial experiences of Bloomsbury’s Leonard Woolf.

All Englishmen who were in their twenties in 1905 had at least one thing in common: They’d watched the world of their childhoods die. Just as they were coming of age, electricity replaced gaslight. Cars and buses replaced horses and bicycles. Urban populations were exploding, mass media and advertising were yammering, and mechanized warfare crouched in the wings, ready and waiting. The early twentieth century looked and sounded and smelled nothing like the late nineteenth. “In those days of the eighties and nineties of the nineteenth century the rhythm of London traffic which one listened to as one fell asleep in one’s nursery was the rhythm of horses’ hooves clopclopping down London streets in broughams, hansom cabs, and four-wheelers,†Woolf would write, toward the end of his life, in the unimaginable year of 1960. “And the rhythm, the tempo got into one’s blood and one’s brain, so that in a sense I have never become entirely reconciled in London to the rhythm and tempo of the whizzing and rushing cars.†Woolf felt displaced, like the hero of H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine, exiled in the future. So did everybody else—Evelyn Waugh once remarked that if he ever got ahold of a time machine, he’d put it in reverse and go backward, into the past.

It’s no accident that both modernism and modern fantasy made their entrances at that moment, in that same displaced generation. It’s rarely remarked upon, but just as Virginia Woolf and Joyce and Hemingway were inventing the modernist novel, Hope Mirrlees and Lord Dunsany and Eric Rücker Eddison were writing the first modern fantasy novels, at least in the form most fans are familiar with. This happened for a reason. Modernism and fantasy were two very different responses to the same disaster: the arrival of the modern era and the death of Woolf’s beloved nursery-world. Though like siblings—or roommates—who are mortally embarrassed by each other, they’re not in the habit of acknowledging the connection. …

But fantasy and modernism aren’t just opposites, they’re mirror images of each other. When the social, cultural, and technological catastrophe that inaugurated the twentieth century took place, leaving the neat, coherent Victorian universe a desecrated ruin, all that was left for writers to do was to sift disconsolately through the rubble and dream of the organic, vital world that had once been. Modernism was pieced together out of the jagged shards of that shattered world—it’s a literature made of fragments, the better to resemble the carnage it represented. Whereas fantasy was a vision of that lost, longed-for world itself, a dream of a medieval England that never was: green, whole, prelapsarian, magical.

Here and there you can spot their shared heritage, the places where modernism and fantasy touch. Modernists and fantasists both rework myths and legends: you can watch King Arthur and his knights trot, obscured but still visible, through Eliot’s “The Waste Land,†Virginia Woolf’s The Waves (in the person of the knightly Percival), and Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (“Arser of the Rum Tippleâ€) to emerge into the sunlit meadows of T. H. White’s The Once and Future King. Modernism and fantasy are set against the same landscapes: verdant preindustrial hills and dark, broken ruins. La tour abolie of “The Waste Land†is the architectural double of Orthanc, the tower of Saruman the White in The Lord of the Rings. The green fields of Narnia abut the “fresh green breast of the new world†that Fitzgerald invokes at the end of The Great Gatsby.

But by the time we reach them, those green fields are always in decline. The spell never lasts. King Arthur is always dying, and the Elves are always shuffling off toward Valinor, where mortals cannot follow. Narnia falls into chaos, then drowns and freezes, and the survivors retreat into Aslan’s Land. We think of fantasy and modernism as worlds apart, but somehow they always end up in the same place. They are perfectly symmetrical. Fantasy is a prelude to the apocalypse. Modernism is the epilogue.

Read the whole thing.

Via Ratak Monodosico.

22 Mar 2013

Projectophile pokes fun at mid-last-century architectural modernism’s dramatic gestures, economies, and built-in lethalities.

The clean lines, the geometric decorative elements, the seamless blending of indoor and outdoor space… I sure do love mid-century modern architecture.

Do you know what I love more? My children. And that is why I will never live in my MCM dream home. Because mid-century modern architecture is designed to KILL YOUR CHILDREN. (Also, moderately clumsy or drunk adults).

Read the whole thing.

Via Walter Olson and Terry Teachout.

Feeds

|