Category Archive 'Democracy'

20 Jun 2014

Robert Tracinski explains what the Patent Office cancelling the Washington Redskin’s trademark shows about the state of American democracy.

This name-bullying has become a kind of sport for self-aggrandizing political activists, because if you can force everyone to change the name of something—a sports team, a city, an entire race of people—it demonstrates your power. This is true even if it makes no sense and especially if it makes no sense. How much more powerful are you if you can force people to change a name for no reason other than because they’re afraid you will vilify them?

Given the equivocal history of the term “redskins†and the differing opinions—among Native Americans as well as everyone else—over whether it is offensive, this was a subjective judgment. (One observer suggests a list of other sports names that could just as plausibly be considered offensive.) When an issue is subjective, it would be wise for the government not to take a stand and let private persuasion and market pressure sort it out.

Ah, but there’s the rub, isn’t it? This ruling happened precisely because the campaign against the Redskins has failed in the court of public opinion. The issue has become the hobby horse of a small group of lefty commentators and politicians in DC, while regular Washingtonians, the people who make up the team’s base of fans and customers, are largely indifferent. So the left resorted to one of its favorite fallbacks. If the people can’t be persuaded, use the bureaucracy—in this case, two political appointees on the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board.

That’s what is disturbing about this ruling. Our system of government depends on the impartial administration of the laws by the executive. In this case, executive officials declared that a private company doesn’t deserve the protection of the law: if the ruling survives an appeal in the courts, the federal government will stop prosecuting violations of the team’s intellectual property rights, potentially costing it millions of dollars.

This ruling isn’t a slippery slope. It’s a slope we’ve already slid down: bureaucrats in Washington are now empowered to make subjective decrees about what is offensive and what will be tolerated, based on pressure from a small clique of Washington insiders. Anyone who runs afoul of these decrees, anyone branded as regressive and politically incorrect, is declared outside the protection of the federal government.

That this is happening, and that we have no idea where it will stop, is what should terrify us—even if, like me, you don’t particularly care one way or the other about the Washington Redskins.

05 Apr 2013

Lars Seier Christensen, co-founder & CEO of Denmark’s Saxo Bank A/S, looks on at the destruction of Cyprus’s economy by the Euro Zone bailout and begins sounding like Tocqueville.

There are very few limits to what you can do to people in the modern interpretation of democracy. A version where only majority rule is required, but where there is no longer a respect for personal negative rights – as we know them from the American Constitution.

The easiest target will always be wealthy people, or even just working people and savers who did the right thing all their lives. As the bloated welfare states begin to collapse under their irresponsible promises, their crumbling value systems and their unsustainable demographics, it will be easy to convince more than 50 percent of voters that confiscating and stealing other people’s money is OK for the greater good. Boston Consulting Group calculated that 28 percent of ALL private wealth is needed to meet just existing debts – not future obligations , mind you – and the money can only come from one place… Your pockets. Beware.

A lot of things have gone wrong over the past few years, but the seeds were planted many years ago. In the form of pressure for more people having the “right†to own their properties, even if they did not fulfill the traditional mortgage criteria – hence subprime. In the form of enormous “entitlements†to not just poor, but also middle-class people in the welfare states – hence ballooning deficits and debt. In the form of a Euro, a grand, political project with no practical foundation – hence crisis after crisis, with the dominoes stretching far into the distance.

The United States has precisely the Liberal political tradition of well-established and legally-recognized Natural Rights protecting property, but we also have Barack Obama and a radical democrat majority in the US Senate sharing views identical to those of European Union socialists and caring absolutely nothing for the American Liberal political tradition, which they neither respect nor understand.

Via Tyler Durden.

09 Dec 2012

The election of Islamic Party municipal councilors in several towns in Belgian is provoking controversy, as the newly elected officials do not bother to conceal their intentions to use democratic means to overthrow democracy and turn Belgium into an Islamic state operating on the basis of Sharia law.

video: December 12, 2012

22 Sep 2012

Beyond a certain point of negative understanding, of course, it is better for someone not to vote.

Joseph C. McMurray discusses the Marquis de Condorcet’s mathematical analysis favoring decision-making by larger numbers of people.

An interesting, if somewhat uncommon, lens through which to view politics is that of mathematics. One of the strongest arguments ever made in favor of democracy, for example, was in 1785 by the political philosopher-mathematician, Nicolas de Condorcet. Because different people possess different pieces of information about an issue, he reasoned, they predict different outcomes from the same policy proposals, and will thus favor different policies, even when they actually share a common goal. Ultimately, however, if the future were perfectly known, some of these predictions would prove more accurate than others. From a present vantage point, then, each voter has some probability of actually favoring an inferior policy. Individually, this probability may be rather high, but collective decisions draw information from large numbers of sources, mistaking mistakes less likely.

To clarify Condorcet’s argument, note that an individual who knows nothing can identify the more effective of two policies with 50% probability; if she knows a lot about an issue, her odds are higher. For the sake of argument, suppose that a citizen correctly identifies the better alternative 51% of the time. On any given issue, then, many will erroneously support the inferior policy, but (assuming that voters form opinions independently, in a statistical sense) a 51% majority will favor whichever policy is actually superior. More formally, the probability of a collective mistake approaches zero as the number of voters grows large.

Condorcet’s mathematical analysis assumes that voters’ opinions are equally reliable, but in reality, expertise varies widely on any issue, which raises the question of who should be voting? One conventional view is that everyone should participate; in fact, this has a mathematical justification, since in Condorcet’s model, collective errors become less likely as the number of voters increases. On the other hand, another common view is that citizens with only limited information should abstain, leaving a decision to those who know the most about the issue. Ultimately, the question must be settled mathematically: assuming that different citizens have different probabilities of correctly identifying good policies, what configuration of voter participation maximizes the probability of making the right collective decision?

It turns out that, when voters differ in expertise, it is not optimal for all to vote, even when each citizen’s private accuracy exceeds 50%. In other words, a citizen with only limited expertise on an issue can best serve the electorate by ignoring her own opinion and abstaining, in deference to those who know more. …

This raises a new question, however, which is who should continue voting: if the least informed citizens all abstain, then a moderately informed citizen now becomes the least informed voter; should she abstain, as well?

Mathematically, it turns out that for any distribution of expertise, there is a threshold above which citizens should continue voting, no matter how large the electorate grows. A citizen right at this threshold is less knowledgeable than other voters, but nevertheless improves the collective electoral decision by bolstering the number of votes. The formula that derives this threshold is of limited practical use, since voter accuracies cannot readily be measured, but simple example distributions demonstrate that voting may well be optimal for a sizeable majority of the electorate.

The dual message that poorly informed votes reduce the quality of electoral decisions, but that moderately informed votes can improve even the decisions made even by more expert peers, may leave an individual feeling conflicted as to whether she should express her tentative opinions, or abstain in deference to those with better expertise. Assuming that her peers vote and abstain optimally, it may be useful to first predict voter turnout, and then participate (or not) accordingly: when half the electorate votes, it should be the better-informed half; when voter turnout is 75%, all but the least-informed quartile should participate. …

If Condorcet’s basic premise is right, an uninformed citizen’s highest contribution may actually be to abstain from voting, trusting her peers to make decisions on her behalf. At the same time, voters with only limited expertise can rest assured that a single, moderately-informed vote can improve upon the decision made by a large number of experts. One might say that this is the true essence of democracy.

His conclusion seems to accord with observed results. Ordinary people are surprisingly well able to correct the follies and delusions which too commonly afflict the experts and elites, but there are also people so clueless that they are always going to vote wrong.

29 Mar 2012

Vladislav Inozemtsev, in the American Interest, argues that democracy has gotten far too democratic, and that over-extended democracy is inevitably going to prove to be democracy’s own worst enemy. He’s perfectly right.

It was therefore no coincidence that democracy developed in national contexts defined by, as noted already, a demos comfortable in its social skin. It is even the case, to take an obviously unsettling example, that American democracy might not have developed as it did had it not been for slavery and acute racial prejudice. Only by separating out of the democratic process those considered at the time not to be a part of the demos could American democracy unfold. That is the other side, so to speak, of the Jacksonian-era expansion of the franchise. …

[E]ven universal secondary education can no longer reliably produce a responsible citizen. Liberal democracy born in the Republic of Letters has to survive in the Empire of Television, where information flows in one direction and need not involve direct response. The civic dialogue that was once the very foundation of democratic decision-making has become a one-way process of convincing voters. The political dialogue of liberal democracies is not just degraded, as is widely acknowledged; it is qualitatively different.

Moreover, as the capacity of citizens to grasp policy issues has eroded from one side, the percentage of citizens expected to grasp them has risen from the other. In Western countries today there is far more inequality within electorates than ever, simply because, as was not the case during the 19th century, everyone above age 18 can vote. …

Democracy was the optimal form of government when voters were capable of making rational choices through an understanding of what was at stake, when they were ready to bear the responsibility for the consequences of their choices, and when the right to vote was understood to be a privilege, or the result of a struggle still remembered. Nowadays it is difficult to shake the impression that democratic societies are rapidly turning into ochlocracies, where the vast majority of citizens, seeing their rights as given and their responsibilities not at all, are easily addled by propaganda, distracted by spectacle and either unable or unwilling to invest the time and energy required to be a responsible democratic actor.

Read the whole thing.

Hat tip to Claire Berlinski.

24 Sep 2011

Jose Orgetga y Gasset

Mark Anthony Signorelli turns his review of Mark Steyn’s After America: Get Ready for Armageddon into an essay supplementary to Steyn’s book, arguing the author’s view of cause and effect can be improved by reading a much earlier (1930) attack on the same forces of dissolution by the Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset. into an essay supplementary to Steyn’s book, arguing the author’s view of cause and effect can be improved by reading a much earlier (1930) attack on the same forces of dissolution by the Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset.

Throughout his book, Steyn catalogues the demoralizing effects of unlimited government upon the American citizenry. No one can ignore the power of the case he presents. But as much as government overreach erodes the character of a people, the debased character of a people manifests itself in arbitrary government. Bad institutions make bad people, but bad people also make bad institutions. Our ugly politics is every bit a reflection of our cultural failings as are our worthless schools. Steyn is not unaware of these facts; one of the passages I found most compelling in his book was when he argues that the truly horrifying thing about the rise of Obama was the fact that the majority of the American people had been duped by such an evident buffoon. Our folly created his administration, and all of its works. So Steyn clearly understands the way a people’s faults can manifest themselves in inept government. Still, the obvious emphasis of his book is on the causal relationship which runs opposite, on the way that inept government debases the character of a people. I think that emphasis is misplaced; I think the effects of a people’s character on the character of their government are more fundamental, more decisive to their happiness, and more subject to reform than the effects which flow from a corrupted government upon the citizenry. Or, to put the point in a different way, I believe that culture is far more consequential for the maintenance of a well-ordered community than politics. Steyn himself advises that, “changing the culture is more important than changing the politics,†but since the emphasis of his book is on the way that bad politics has changed our culture for the worse, he actually seems to undermine this bit of advice.

The book that most effectively delineates the ruinous social mechanisms of liberal democracy is The Revolt of the Masses , by the early twentieth-century philosopher Jose Ortega y Gasset. For Ortega, modern western society was marked by the rise to power of the “mass-man,†the unqualified or uncultivated man, who, lacking all necessary intellectual and moral training in the duties of civic life, had nonetheless asserted his immutable right to impose his own mediocrity of spirit upon society: “The characteristic of the hour is that the commonplace mind, knowing itself to be commonplace, has the assurance to proclaim the rights of the commonplace and to impose them wherever it will.†The mass-man is not bound by any traditions or maxims of prudence; he cares only about having his own way in the world. And when he is taught (as all modern political theory teaches him) that the state is a manifestation of his own will, he freely grants it an unlimited scope of action, just as he (theoretically) grants himself a perfect freedom of action: “This is the gravest danger that today threatens civilization: State intervention, the absorption of all spontaneous social effort by the State…when the mass suffers any ill-fortune, or simply feels some strong appetite, its great temptation is that permanent, sure possibility of obtaining everything – merely by touching a button and setting the mighty machine in motion.†The consequences of this trend are catastrophic: , by the early twentieth-century philosopher Jose Ortega y Gasset. For Ortega, modern western society was marked by the rise to power of the “mass-man,†the unqualified or uncultivated man, who, lacking all necessary intellectual and moral training in the duties of civic life, had nonetheless asserted his immutable right to impose his own mediocrity of spirit upon society: “The characteristic of the hour is that the commonplace mind, knowing itself to be commonplace, has the assurance to proclaim the rights of the commonplace and to impose them wherever it will.†The mass-man is not bound by any traditions or maxims of prudence; he cares only about having his own way in the world. And when he is taught (as all modern political theory teaches him) that the state is a manifestation of his own will, he freely grants it an unlimited scope of action, just as he (theoretically) grants himself a perfect freedom of action: “This is the gravest danger that today threatens civilization: State intervention, the absorption of all spontaneous social effort by the State…when the mass suffers any ill-fortune, or simply feels some strong appetite, its great temptation is that permanent, sure possibility of obtaining everything – merely by touching a button and setting the mighty machine in motion.†The consequences of this trend are catastrophic:

The result of this tendency will be fatal. Spontaneous social action will be broken up over and over again by State intervention; no new seed will be able to fructify. Society will have to live for the State, man for the governmental machine. And as, after all, it is only a machine whose existence and maintenance depend on the vital supports around it, the State, after sucking out the very marrow of society, will be left bloodless, a skeleton, dead with that rusty death of machinery, more gruesome than the death of a living organism.

Exactly as Steyn describes it in his book, some eighty years later. But what Ortega makes us see is that “big government†results from the prior moral corruption of the people, in particular from their unbounded self-love and self-assurance. It destroys them in the end, but at the first, it was their creature.

Read the whole thing. This one is a must-read.

Hat tip to Karen L. Myers.

27 Feb 2011

Historian Bernard Lewis discusses the causes of unrest in the Middle East and is pessimistic about long-term prospects for democracy. His take on all this makes quite a contrast with the kind of naive optimism we read in conventional news sources in the West.

The Arab masses certainly want change. And they want improvement. But when you say do they want democracy, that’s a more difficult question to answer. What does “democracy†mean? It’s a word that’s used with very different meanings, even in different parts of the Western world. And it’s a political concept that has no history, no record whatever in the Arab, Islamic world.

In the West, we tend to get excessively concerned with elections, regarding the holding of elections as the purest expression of democracy, as the climax of the process of democratization. Well, the second may be true – the climax of the process. But the process can be a long and difficult one. Consider, for example, that democracy was fairly new in Germany in the inter-war period and Hitler came to power in a free and fair election.

We, in the Western world particularly, tend to think of democracy in our own terms – that’s natural and normal – to mean periodic elections in our style. But I think it’s a great mistake to try and think of the Middle East in those terms and that can only lead to disastrous results, as you’ve already seen in various places. They are simply not ready for free and fair elections.

One of the most moving experiences of my life was in the year 1950, most of which I spent in Turkey. That was the time when the Turkish government held a free and genuinely fair election – the election of 1950 – in which that government was defeated, and even more remarkably the government then quietly and decently withdrew from power and handed over power to the victorious opposition.

What followed I can only describe as catastrophic. Adnan Menderes, the leader of the party which won the election, which came to power by their success in the election, soon made it perfectly clear that he had no intention whatever of leaving by the same route by which he had come, that he regarded this as a change of regime, and that he had no respect at all for the electoral process.

And people in Turkey began to realize this. I remember vividly sitting one day in the faculty lounge at the school of political sciences in Ankara. This would have been after several years of the Menderes regime. We were sitting in the faculty lounge with some of the professors discussing the history of different political institutions and forms. And one of them suddenly said, to everyone’s astonishment, “Well, the father of democracy in Turkey is Adnan Menderes.â€

The others looked around in bewilderment. They said, “Adnan Menderes, the father of Turkish democracy? What do you mean?†Well, said this professor, “he raped the mother of democracy.†It sounds much better in Turkish…

This happened again and again and again. You win an election because an election is forced on the country. But it is seen as a one-way street. Most of the countries in the region are not yet ready for elections. …

I can imagine a situation in which the Muslim Brotherhood and other organizations of the same kind obtain control of much of the Arab world. It’s not impossible. I wouldn’t say it’s likely, but it’s not unlikely.

And if that happens, they would gradually sink back into medieval squalor.

Remember that according to their own statistics, the total exports of the entire Arab world other than fossil fuels amount to less than those of Finland, one small European country. Sooner or later the oil age will come to an end. Oil will be either exhausted or superseded as a source of energy and then they have virtually nothing. In that case it’s easy to imagine a situation in which Africa north of the Sahara becomes not unlike Africa south of the Sahara. …

There’s a common theme of anger and resentment. And the anger and resentment are universal and well-grounded. They come from a number of things. First of all, there’s the obvious one – the greater awareness that they have, thanks to modern media and modern communications, of the difference between their situation and the situation in other parts of the world. I mean, being abjectly poor is bad enough. But when everybody else around you is pretty far from abjectly poor, then it becomes pretty intolerable.

Another thing is the sexual aspect of it. One has to remember that in the Muslim world, casual sex, Western-style, doesn’t exist. If a young man wants sex, there are only two possibilities – marriage and the brothel. You have these vast numbers of young men growing up without the money, either for the brothel or the brideprice, with raging sexual desire. On the one hand, it can lead to the suicide bomber, who is attracted by the virgins of paradise – the only ones available to him. On the other hand, sheer frustration. …

There was a little Arab boy whose arm was broken by an Israeli policeman during a demonstration and he appeared the next day on Israeli television with a bandage on his arm, denouncing Israeli brutality. I was in Amman at the time, watching this. And sitting next to me was an Iraqi, who had fled Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, and he looked at this with his jaw dropping and he said, “I would gladly let Saddam Hussein break both my arms and both my legs if he would let me talk like that on Iraqi television.†…

The sort of authoritarian, even dictatorial regimes, that rule most of the countries in the modern Islamic Middle East, are a modern creation. They are a result of modernization. The pre-modern regimes were much more open, much more tolerant. You can see this from a number of contemporary descriptions. And the memory of that is still living.

It was a British naval officer called Slade who put it very well. He was comparing the old order with the new order, created by modernization. He said that “in the old order, the nobility lived on their estates. In the new order, the state is the estate of the new nobility.†I think that puts it admirably. …

In the Western world, we talk all the time about freedom. In the Islamic world, freedom is not a political term. It’s a legal term: Freedom as opposed to slavery. This was a society in which slavery was an accepted institution existing all over the Muslim world. You were free if you were not a slave. It was entirely a legal and social term, with no political connotation whatsoever. You can see in the ongoing debate in Arabic and other languages the puzzlement with which the use of the term freedom was first perceived.

They just didn’t understand it. I mean, what does this have to do with politics or government? Eventually, they got the message. But it’s still alien to them.

17 Dec 2010

Kenneth Minogue’s The Servile Mind: How Democracy Erodes the Moral Life seems to be the conservative book most of us will be reading during the upcoming holidays. seems to be the conservative book most of us will be reading during the upcoming holidays.

Online reviews are currently scarce, but Anthony Baird did a decent job on Amazon.

Kenneth Minogue has brilliantly deconstructed the way that modern democracies have assumed for themselves the moral judgements that individuals once decided for themselves. Take obesity. Getting fat is surely one of the ultimate personal decisions, but no, it is apparently a `health’ issue now, and is properly the concern of the whole of society. This is because the populace has surrendered to the State the obligation to take care of the nation’s health, and since obesity is a major factor in the expense that the health provider must pay, the state now requires us all to be slim. Successfully elected politicians praise the electorate for their good sense in electing them to office, and then privately despair at the non “politically correct” views held by those same voters on the matters of multiculturalism, capital punishment or sex.

With the State taking over more and more of the obligations that private citizens used to consider were their own concern, (and levying high rates of tax to fund them), then this leaves those same citizens free to spend the rest of their incomes on personal pleasures, secure in the knowledge that their education, health and pensions are taken care of. While all this sounds like some Utopia, it is actually more of a “Brave New World”.

The folks at Maggie Farm and I tend very frequently to think alike. I was amused to find the New Junkie had slightly preceded me today in noticing the same book.

13 Jul 2010

Neil Reynolds comments on the financial collapse of the European welfare state.

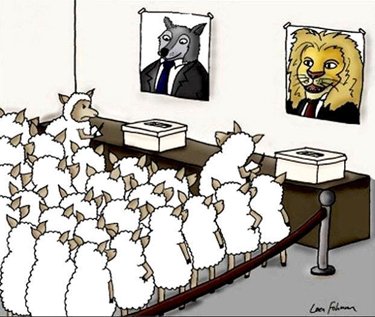

Democracies produced Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, fulfilling the expectation of Socrates and Machiavelli that democracies end in tyranny. Now democracies are fulfilling the complementary expectation of Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman that democracies end in bankruptcy. Put a democracy in charge of the Sahara, Mr. Friedman once said, and sand itself will become scarce. Democracies are indeed profligate trustees – or have been for the past 30 or 40 years. Mr. Friedman’s primary fret, though, was the tendency of democracy to centralize political and economic power in the same hands. Most critiques of democracy reflect this elemental distrust. “Democracy is two wolves and a lamb,†Benjamin Franklin reputedly said, “voting on what to have for lunch.â€

A must read article.

14 Jun 2010

Kenneth Minogue has a very important essay on the propensity of the modern democratic state to invade and to attempt to control regions of behavior and thought previously regarded as personal and private.

[W]hile democracy means a government accountable to the electorate, our rulers now make us accountable to them. Most Western governments hate me smoking, or eating the wrong kind of food, or hunting foxes, or drinking too much, and these are merely the surface disapprovals, the ones that provoke legislation or public campaigns. We also borrow too much money for our personal pleasures, and many of us are very bad parents. Ministers of state have been known to instruct us in elementary matters, such as the importance of reading stories to our children. Again, many of us have unsound views about people of other races, cultures, or religions, and the distribution of our friends does not always correspond, as governments think that it ought, to the cultural diversity of our society. We must face up to the grim fact that the rulers we elect are losing patience with us. …

Our rulers, then, increasingly deliberate on our behalf, and decide for us what is the right thing to do. The philosopher Socrates argued that the most important activity of a human being was reflecting on how one ought to live. Most people are not philosophers, but they cannot avoid encountering moral issues. The evident problem with democracy today is that the state is pre-empting—or “crowding out,†as the economists say—our moral judgments. Nor does the state limit itself to mere principle. It instructs us on highly specific activities, ranging from health provision to sexual practices. Yet decisions about how we live are what we mean by “freedom,†and freedom is incompatible with a moralizing state. That is why I am provoked to ask the question: can the moral life survive democracy?

Read the whole thing.

Hat tip to Gerard Van Der Leun via the News Junkie.

22 Mar 2010

Megan McArdle explains why the democrats’ success in getting their way represents a procedural precedent likely to change the legislative process permanently.

Regardless of what you think about health care, tomorrow we wake up in a different political world.

Parties have passed legislation before that wasn’t broadly publicly supported. But the only substantial instances I can think of in America are budget bills and TARP–bills that the congressmen were basically forced to by emergencies in the markets.

One cannot help but admire Nancy Pelosi’s skill as a legislator. But it’s also pretty worrying. Are we now in a world where there is absolutely no recourse to the tyranny of the majority? Republicans and other opponents of the bill did their job on this; they persuaded the country that they didn’t want this bill. And that mattered basically not at all. If you don’t find that terrifying, let me suggest that you are a Democrat who has not yet contemplated what Republicans might do under similar circumstances. Farewell, social security! Au revoir, Medicare! The reason entitlements are hard to repeal is that the Republicans care about getting re-elected. If they didn’t–if they were willing to undertake this sort of suicide mission–then the legislative lock-in you’re counting on wouldn’t exist.

Oh, wait–suddenly it doesn’t seem quite fair that Republicans could just ignore the will of their constituents that way, does it? Yet I guarantee you that there are a lot of GOP members out there tonight who think that they should get at least one free “Screw You” vote to balance out what the Democrats just did.

But I hope they don’t. What I hope is that the Democrats take a beating at the ballot boxand rethink their contempt for those mouth-breathing illiterates in the electorate. I hope Obama gets his wish to be a one-term president who passed health care. Not because I think I will like his opponent–I very much doubt that I will support much of anything Obama’s opponent says. But because politicians shouldn’t feel that the best route to electoral success is to lie to the voters, and then ignore them.

Read the whole thing.

/div>

Feeds

|