Category Archive 'Friedrich Nietzsche'

24 Nov 2018

This must be the European edition dust jacket.

Hugo Drochon, reviewing Sue Prideaux’s new Nietzsche biography, I Am Dynamite in the Irish Times, explains that this one is a revolutionary revisionist bio that fans of Fred will have to read. I bought mine.

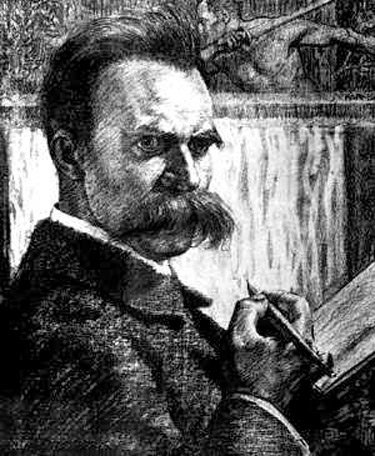

On the morning of January 3rd, 1889 a half-blind German professor, sporting a luxurious moustache, left his lodgings on the third floor of Via Carlo Alberto 6 in Turin. He was used to taking his daily walk through the famous arcades of the city, which shielded him from the light, and along the banks of the river Po. He would walk up to five hours a day, which explained his muscular frame: somewhat in dire contrast to the various illnesses that notoriously plagued his life.

But that day he did not get very far. He walked less than 200m to the Piazza Carignano, and what happened next is the stuff of legend: seeing an old recalcitrant horse being flogged mercilessly by its owner, the professor threw his arms around the horse to protect it – perhaps even whispering “Mother, I have been stupid†in its ear (how can anyone have heard that?) – and collapsing. He was saved from being escorted by two policemen to the asylum by his landlord, Davide Fino, who brought him home. We might never know exactly what happened on that fateful day, but one thing is certain: the productive and intellectual life of the great philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche had come to an end.

In her wonderfully gripping new biography of Nietzsche – the type you stay in bed all Sunday just to finish – Sue Prideaux casts doubt on this story. Indeed, the horse only makes an appearance in the legend 11 years later – in 1900, the year of Nietzsche’s death – when a journalist interviewed Fino, the landlord, about the events of the day. And only in the 1930s – more than 40 years later – do we hear about the horse being beaten and Nietzsche breaking down in tears; this time in an interview with Fino’s son, Ernesto, who would have been about 14 at the time.

Despite no corroboration on the German side – from neither his sister nor his friend Overbeck, who brought him back to Basle – the “Nietzsche horse memeâ€, to put it in today’s terms, has proved hugely popular. It features in Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and the horse itself has got its own biopic in the form of an 2011 film The Turin Horse by Hungarian film-makers Béla Tarr and Ãgnes Hranitzky, which proposes a storyline of what happened to the horse after the event. To make things even stranger, the story of a horse being flogged to death appears in Nietzsche’s favourite author Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, written when the latter was 44: exactly Nietzsche’s age when he broke down.

Prideaux casts even more doubt on the cause usually attributed to this insanity: syphilis. Popularised by Thomas Mann’s novel Doctor Faustus, which has a Nietzsche-like character contract syphilis in a brothel, the evidence simply doesn’t stack up. Although diagnosed as such when admitted to the asylum in Basle, Nietzsche showed none of symptoms now associated with it: no tremor, faceless expression or slurred speech. If he was at an advanced stage of dementia caused by syphilis, Nietzsche should have died within the next two years; five max. He lived for another 11. The two infections he told the doctors about were for gonorrhoea, contracted when he was a medical orderly during the Franco-Prussian War.

Instead Prideaux puts forward the – correct – view that Nietzsche probably died of a brain tumour, the same “softening of the brain†that had taken away his father, a rural pastor, when Nietzsche was a boy. Indeed both sides of the family showed signs of neurological problems, or of suffering of “nervesâ€, as one put it at the time. Nietzsche’s younger sister Elisabeth certainly seemed prone, in posthumously making him palatable to the Nazis in her Nietzsche Archive in Weimar, to a degree of megalomania herself (she had herself buried in the middle of the Nietzsche family burial ground, on the spot originally reserved for her brother).

At stake is whether Nietzsche’s writings, and especially his theory of the Übermensch, should just be dismissed as the ravings of a madman. Here the story of the horse takes on particular importance: if true it would mean Nietzsche repented his views, asking for forgiveness for having demanded that modern man should “overcome†himself, to become “hard†by eschewing pity. This is certainly Kundera’s view, and it makes for a much nicer, more docile Nietzsche. But if there is no horse, or at least if there is no sobbing and protecting a flogged horse – that there is a mental breakdown is beyond doubt – then Nietzsche means what he says and his thinking is, in the words of Prideaux, dynamite.

RTWT

11 Feb 2018

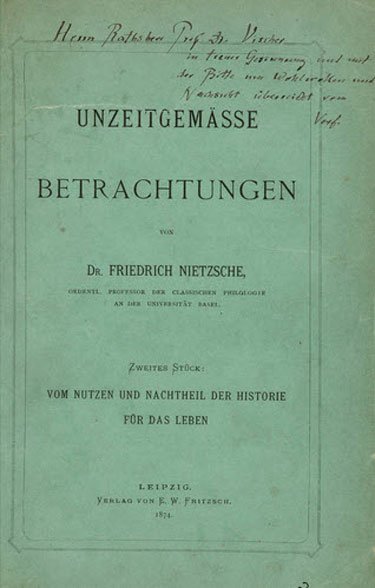

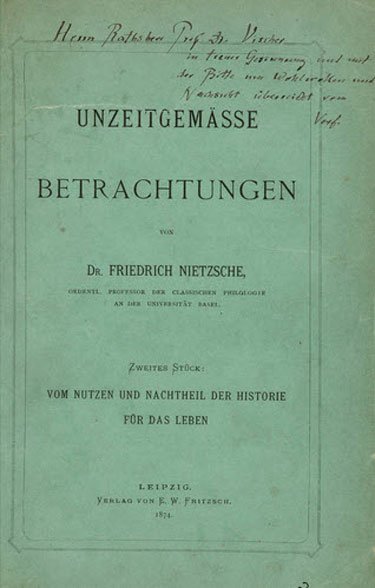

Heritage Auctions, 2018 March 7 Rare Books Signature Auction – New York #6186:

Friederich Nietzsche’s Untimely Meditations, 1874, an early work by this major philosopher with author’s presentation inscription.

Opening bid: $15,000 (plus 25% buyer premium.)

Friedrich Nietzsche. Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen. Zweites Stück: Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben. [Untimely Meditations, Part II]. Leipzig: E. W. Fritzsch, 1874. First edition of the second work (of four completed) in Nietzsche’s Untimely Meditations series, this being on the subject of history; association copy, inscribed by the author on the front wrapper to Wilhelm Vischer Bilfinger who appointed Nietzsche, sans dissertation, to the First Chair of Philology at the University of Basel: “Herr Rathsherr Prof. Dr. Vischer / in treuer Gesinnung und mit / der Bitte um Wohlwollen und / Nachsicht überreicht vom / Verf.” Octavo (8.75 x 5.5 inches; 223 x 140 mm.). 111, [1, printer’s note] pages. Twentieth century green cloth, spine lettered in gilt; edges sprinkled gray; patterned endpapers; publisher’s bluish green wrappers laid down and inserted. Spine gently leaning, spine ends and corners very lightly worn; boards very slightly splayed with a touch of soiling. Front endpaper with some light pencil erasure causing some minimal bruising; wrappers very lightly soiled; front wrapper with a couple horizontal closed tears, expertly mended when laid down, just a single letter of the inscription affected (the “N” in “Nachsicht”); rear wrapper with some paper filled in in the gutter margin; title-leaf faintly browned; text-block with some trace foxing. Near fine. Dr. Vischer died shortly after publication, in July of 1874, making this an early presentation. Carl Pletsch. Young Nietzsche. New York: 1991. pp. 99-100. From the Marilyn R. Duff Collection.

23 May 2017

“The State is the coldest of all cold monsters- and this lie creeps from its mouth: “I, the state, am the peopleâ€.”

— Friedrich Nietzscheâ€

09 May 2016

Christopher Bray calls Daniel Blue’s forthcoming (in June) biography of the young philosopher The Making of Friedrich Nietzsche: The Quest for Identity, 1844-1869 “lacklustre,” but since he’s wrong about the survival of the photo of military Fred with sword, who knows what else he’s wrong about?

(The current price quoted by Amazon is awfully steep. Let’s hope that a better deal becomes available when the book is actually released.)

Had you been down at Naumburg barracks early in March 1867, you might have seen a figure take a running jump at a horse and thud down front first on the pommel with a yelp. This was Friedrich Nietzsche, midway through his 22nd year and, thanks to a sickly childhood, no stranger to hospitals. The doctors were obliged to operate, and Nietzsche lost several ribs and part of his sternum, leaving him not so much pigeon-chested as angle-grinded. Once recovered, he celebrated by having his picture taken in full uniform, sabre at the ready, glaring at the ‘miserable photographer’ like a warrior set for battle. Alas for comedy, this portrait is lost to history.

Daniel Blue has no such regrets. He is convinced the photo would have been ‘unflattering’ — though nowhere near as unflattering as the picture Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche painted of her brother after his death in 1900. …

19 Jan 2015

Friederich Nietzsche’s Malling-Hansen Writing Ball, 1882, an example of the world’s first commercially produced typewriter.

Wikipedia:

In 1881, when he had serious problems with his sight, Friedrich Nietzsche wanted to buy a typewriter to enable him to continue his writing, and from letters to his sister it is known that he personally was in contact with “the inventor of the typewriter, Mr Malling-Hansen from Copenhagen”. He mentioned to his sister that he had received letters and also a typewritten postcard as an example. Nietzsche received his writing ball in 1882 directly from the inventor in Copenhagen, Denmark, Rasmus Malling-Hansen. It was the newest model, the portable tall one with a color ribbon, serial number 125, and several typescripts are known to have been written by him on this writing ball (approximately 60). It is known that Nietzsche was also familiar with the newest model from E. Remington and Sons (model 2), but he wanted to buy a portable typewriter, so he chose to buy the Malling-Hansen writing ball, as this model was lightweight and easy to carry. Unfortunately, Nietzsche wasn’t totally satisfied with his purchase and never really mastered the use of the instrument. A number of theories have been advanced to explain why Nietzsche did not make more use of it. For example, Rüdiger Safranski indicates it was “defective”. New research indicates Nietzsche was not aware that his trouble in using the machine had been caused by damage to it during transportation to Genoa in Italy, where he lived at the time, and when he turned to a mechanic who had no typewriter repair skills, the man managed to damage the writing ball even more. Nietzsche claimed that his thoughts were influenced by his use of a typewriter (“Our writing instruments contribute to our thoughts”, 1882).

Nietzsche’s Writing Ball

21 Sep 2013

Sils-Maria, Switzerland. 2004. Photograph: Patrick Lakey

From Curtis Cate’s Friedrich Nietszche.

With a Spartan rigour which never ceased to amaze his landlord-grocer, Nietzsche would get up every morning when the faintly dawning sky was still grey, and, after washing himself with cold water from the pitcher and china basin in his bedroom and drinking some warm milk, he would, when not felled by headaches and vomiting, work uninterruptedly until eleven in the morning. He then went for a brisk, two-hour walk through the nearby forest or along the edge of Lake Silvaplana (to the north-east) or of Lake Sils (to the south-west), stopping every now and then to jot down his latest thoughts in the notebook he always carried with him. Returning for a late luncheon at the Hôtel Alpenrose, Nietzsche, who detested promiscuity, avoided the midday crush of the table d’hôte in the large dining-room and ate a more or less ‘private’ lunch, usually consisting of a beefsteak and an ‘unbelievable’ quantity of fruit, which was, the hotel manager was persuaded, the chief cause of his frequent stomach upsets. After luncheon, usually dressed in a long and somewhat threadbare brown jacket, and armed as usual with notebook, pencil, and a large grey-green parasol to shade his eyes, he would stride off again on an even longer walk, which sometimes took him up the Fextal as far as its majestic glacier. Returning ‘home’ between four and five o’clock, he would immediately get back to work, sustaining himself on biscuits, peasant bread, honey (sent from Naumburg), fruit and pots of tea he brewed for himself in the little upstairs ‘dining-room’ next to his bedroom, until, worn out, he snuffed out the candle and went to bed around 11 p.m.

Hat tip to Rhys Trantner.

20 May 2013

Gay Marriage Equality symbol used on social media

Mark Rothko, Black on Maroon, 1958, Tate Gallery

Nihilism as a psychological state will have to be reached, first, when we have sought a “meaning†in all events that is not there: so the seeker eventually becomes discouraged. Nihilism, then, is the recognition of the long waste of strength, the agony of the “in vain,†insecurity, the lack of any opportunity to recover and to regain composure—being ashamed in front of oneself, as if one had deceived oneself all too long.—This meaning could have been: the “fulfillment†of some highest ethical canon in all events, the moral world order; or the growth of love and harmony in the intercourse of beings; or the gradual approximation of a state of universal happiness; or even the development toward a state of universal annihilation—any goal at least constitutes some meaning. What all these notions have in common is that something is to be achieved through the process—and now one realizes that becoming aims at nothing and achieves nothing.— Thus, disappointment regarding an alleged aim of becoming as a cause of nihilism: whether regarding a specific aim or, universalized, the realization that all previous hypotheses about aims that concern the whole “evolution†are inadequate (man no longer the collaborator, let alone the center, of becoming).

Nihilism as a psychological state is reached, secondly, when one has posited a totality, a systematization, indeed any organization in all events, and underneath all events, and a soul that longs to admire and revere has wallowed in the idea of some supreme form of domination and administration (—if the soul be that of a logician, complete consistency and real dialectic are quite sufficient to reconcile it to everything). Some sort of unity, some form of “monismâ€: this faith suffices to give man a deep feeling of standing in the context of, and being dependent on, some whole that is infinitely superior to him, and he sees himself as a mode of the deity.—“The well-being of the universal demands the devotion of the individualâ€â€”but behold, there is no such universal! At bottom, man has lost the faith in his own value when no infinitely valuable whole works through him; i. e., he conceived such a whole in order to be able to believe in his own value.

Nihilism as psychological state has yet a third and last form.

Given these two insights, that becoming has no goal and that underneath all becoming there is no grand unity in which the individual could immerse himself completely as in an element of supreme value, an escape remains: to pass sentence on this whole world of becoming as a deception and to invent a world beyond it, a true world. But as soon as man finds out how that world is fabricated solely from psychological needs, and how he has absolutely no right to it, the last form of nihilism comes into being: it includes disbelief in any metaphysical world and forbids itself any belief in a true world. Having reached this standpoint, one grants the reality of becoming as the only reality, forbids oneself every kind of clandestine access to afterworlds and false divinities—but cannot endure this world though one does not want to deny it.

What has happened, at bottom? The feeling of valuelessness was reached with the realization that the overall character of existence may not be interpreted by means of the concept of “aim,†the concept of “unity,†or the concept of “truth.†Existence has no goal or end; any comprehensive unity in the plurality of events is lacking: the character of existence is not “true,†is false. One simply lacks any reason for convincing oneself that there is a true world. Briefly: the categories “aim,†“unity,†“being†which we used to project some value into the world—we pull out again; so the world looks valueless.

— Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power

Quoted directly from Fred Lapides.

07 Jun 2010

Peter Singer

…for many a time

I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath;

Now more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon the midnight with no pain.

–John Keats

In the New York Times, Princeton’s professional ethicist supreme Peter Singer admires the work of antinatalist South African philosopher David Benatar:

Schopenhauer’s pessimism has had few defenders over the past two centuries, but one has recently emerged, in the South African philosopher David Benatar, author of a fine book with an arresting title: “Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence.†One of Benatar’s arguments trades on something like the asymmetry noted earlier. To bring into existence someone who will suffer is, Benatar argues, to harm that person, but to bring into existence someone who will have a good life is not to benefit him or her. Few of us would think it right to inflict severe suffering on an innocent child, even if that were the only way in which we could bring many other children into the world. Yet everyone will suffer to some extent, and if our species continues to reproduce, we can be sure that some future children will suffer severely. Hence continued reproduction will harm some children severely, and benefit none.

Benatar also argues that human lives are, in general, much less good than we think they are. We spend most of our lives with unfulfilled desires, and the occasional satisfactions that are all most of us can achieve are insufficient to outweigh these prolonged negative states. If we think that this is a tolerable state of affairs it is because we are, in Benatar’s view, victims of the illusion of pollyannaism. This illusion may have evolved because it helped our ancestors survive, but it is an illusion nonetheless. If we could see our lives objectively, we would see that they are not something we should inflict on anyone.

Here is a thought experiment to test our attitudes to this view. Most thoughtful people are extremely concerned about climate change. Some stop eating meat, or flying abroad on vacation, in order to reduce their carbon footprint. But the people who will be most severely harmed by climate change have not yet been conceived. If there were to be no future generations, there would be much less for us to feel to guilty about.

So why don’t we make ourselves the Last Generation on Earth? If we would all agree to have ourselves sterilized then no sacrifices would be required — we could party our way into extinction! …

Is a world with people in it better than one without? Put aside what we do to other species — that’s a different issue. Let’s assume that the choice is between a world like ours and one with no sentient beings in it at all. And assume, too — here we have to get fictitious, as philosophers often do — that if we choose to bring about the world with no sentient beings at all, everyone will agree to do that. No one’s rights will be violated — at least, not the rights of any existing people. Can non-existent people have a right to come into existence?

I do think it would be wrong to choose the non-sentient universe. In my judgment, for most people, life is worth living. Even if that is not yet the case, I am enough of an optimist to believe that, should humans survive for another century or two, we will learn from our past mistakes and bring about a world in which there is far less suffering than there is now. But justifying that choice forces us to reconsider the deep issues with which I began. Is life worth living? Are the interests of a future child a reason for bringing that child into existence? And is the continuance of our species justifiable in the face of our knowledge that it will certainly bring suffering to innocent future human beings?

Friedrich Nietszche (Thus Spake Zarathustra, 1883-1885, prologue, §5) predicted with complete accuracy that the result of nihilism would be Benatars and Singers.

Alas! There cometh the time when man will no longer give birth to any star. Alas! There cometh the time of the most despicable man, who can no longer despise himself.

Lo! I show you THE LAST MAN.

“What is love? What is creation? What is longing? What is a star?”–so asketh the last man and blinketh.

The earth hath then become small, and on it there hoppeth the last man who maketh everything small. His species is ineradicable like that of the ground-flea; the last man liveth longest.

“We have discovered happiness”–say the last men, and blink thereby.

They have left the regions where it is hard to live; for they need warmth. One still loveth one’s neighbour and rubbeth against him; for one needeth warmth.

Turning ill and being distrustful, they consider sinful: they walk warily. He is a fool who still stumbleth over stones or men!

A little poison now and then: that maketh pleasant dreams. And much poison at last for a pleasant death.

One still worketh, for work is a pastime. But one is careful lest the pastime should hurt one.

One no longer becometh poor or rich; both are too burdensome. Who still wanteth to rule? Who still wanteth to obey? Both are too burdensome.

No shepherd, and one herd! Every one wanteth the same; every one is equal: he who hath other sentiments goeth voluntarily into the madhouse.

“Formerly all the world was insane,”–say the subtlest of them, and blink thereby.

They are clever and know all that hath happened: so there is no end to their raillery. People still fall out, but are soon

reconciled–otherwise it spoileth their stomachs.

They have their little pleasures for the day, and their little pleasures for the night, but they have a regard for health.

“We have discovered happiness,”–say the last men, and blink thereby.

25 Mar 2008

Und wenn du lange in einen Abgrund blickst, blickt der Abgrund auch in dich hinein. (And when you stare long into the Abyss, the Abyss looks also into you.)

Friedrich Nietzsche, Jenseits von Gut und Böse (Beyond Good and Evil), 4:146

link

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Friedrich Nietzsche' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|