Category Archive 'The Beatles'

19 Jun 2024

The New Yorker recounts the complicated history of a preposterously valuable timepiece.

[S]ometime around 2007, in the early days of social media, a new kind of watch obsessive materialized, equipped with native computer skills and an appreciation for the places where pop culture and the luxury market intersect. In those pre-Instagram years, fanboy wonks traded watch esoterica online: an image of Picasso wearing a lost Jaeger-LeCoultre; Castro with two trendy Rolexes strapped to one arm; Brando, on the set of “Apocalypse Now,” “flexing,” as watch geeks say, a Rolex GMT-Master without its timing bezel, a modification he made to better inhabit the role of Kurtz; and—the Google image-search find of them all—two frames of an uncredited snapshot of Lennon and his Patek.

“I’m not a watch guy,” Sean Lennon said. “I’d be terrified to wear anything of my dad’s. I never even played one of his guitars.”

Since its discovery, around 2011, the image has appeared online again and again, fuelling a speculative frenzy about what the watch—which cost around twenty-five thousand dollars at Tiffany in 1980—might bring at auction today, with estimates ranging from ten million to forty million dollars. (Bloomberg’s Subdial Watch Index tracks the value of a bundle of watches produced by Rolex, Patek, and Audemars Piguet, like an E.T.F.; the Boston Consulting Group reported that, between 2018 and 2023, a similar selection outperformed the S. & P. 500 by twelve per cent. In 2017, Paul Newman’s Rolex Daytona broke records by selling at auction for $17.8 million.) But all the clickbait posts about the Lennon Patek, as it had come to be known, were regurgitations that contained few facts. There was never a mention of who took the photo, where it was taken, or even where the watch might be.

During the long, dull days of the pandemic, I decided to see what I could find out. Several years went by, as I traced the journey of the watch from where it was stowed after Lennon’s death—a locked room in his Dakota apartment—to when it was stolen, apparently in 2005. From there, it moved around Europe and the watch departments of two auction houses, before becoming the subject of an ongoing lawsuit, in Switzerland, to determine whether the watch’s rightful owner is Ono or an unnamed man a Swiss court judgment refers to as Mr. A, who claims to have bought the watch legally in 2014.

Having reached its final appeal—Ono has so far prevailed—the case is now in the hands of the Tribunal Fédéral, Switzerland’s Supreme Court, which is expected to render a verdict later this year. Meanwhile, the watch continues to sit in an undisclosed location in Geneva, a city that specializes in the safe, secret storage of lost treasures.

RTWT

15 May 2022

Ryan Ritchie penned a letter to billionaire Sir Paul complaining about his ticket prices.

Let’s, Paul, for the sake of argument, say I want my parents to, you know, actually see you, so I buy three seats in section C129. Those seats are $450. Each. And, as Ticketmaster reminds me, “+ fees.”

I can’t surprise my parents with tickets to see Sir Paul freakin’ McCartney only for them to sit halfway to LAX. That’s like giving a child a toy without batteries. A $600 toy, mind you.

That $600 doesn’t include parking. I’ve yet to visit SoFi Stadium, but let’s pretend parking is $20. We both know it’s not $20, but let’s pretend. That’s $620. My parents don’t drink alcohol, so I’m definitely saving money on beers, but — and I know you don’t live here — have you any idea of current gas prices? You probably don’t because if I wrote “The Long and Winding Road” I wouldn’t know gas prices, either. Paul, gas is expensive. Like, so expensive that I’m writing to you and wasting space by talking about gas.

Conservatively, if I bought the cheapest tickets, I would be looking at $700 to take my parents to your show and sit far enough away that we will not be able to see you. To be frank, Paul, that sucks. I don’t want to spend that kind of money to stare at the big screens that I am sure will be on stage. Certainly, you’ve heard of YouTube. My parents and I can get the same experience tomorrow morning for much less money.

Paul, serious question: What the fuck?

Can I take a guess before you answer? You probably have no idea how much tickets are to your show in Inglewood or any show on your “Got Back” tour. You also probably have no idea how many tickets are being sold by Ticketmaster as “Verified Resale Tickets,” which appears to make the prices increase and fluctuate. But what about the tickets that are not resales? Why are those so expensive? Surely someone in your camp knows how much tickets cost to your shows. And surely they can be cheaper.

The COVID-19 lockdown meant lots of people didn’t make money. I’m assuming your band members fall into this category. If so, I sympathize with them just like I sympathize with everyone whose income suffered due to the pandemic. What about them, Paul, your fans? What about people like me, people who want to see you, to take their parents out for a night to hear the music of their youth, the music of my youth, the music of all our youths?

Should that night cost $700?

Call me naïve, but I don’t think any three people should have to pay $700 to attend any concert that doesn’t include Elvis walking onto the stage and confirming he faked his 1977 death. That is worth $700.

Sure, you are Paul McCartney, but I grew up going to five-dollar punk shows where the musicians were two feet away from me and my friends. Those were the best bands I’ve ever seen and the best times of my life. You wrote the soundtrack to my life, to my parents’ lives, to so many people’s lives, but even you, Paul, can’t convince me that any concert is worth $190 a ticket to sit as far away as physically possible.

I’m a bass player and songwriter and I’ve been vegan for 18 years (vegetarian for seven before that), which means there’s pretty much nothing you could do to get me to stop loving you and your music. If this letter means anything to you, hopefully it’s this: The idea of seeing you in concert is worth every cent in my bank account and for the first time in my life, I can afford $700 and not worry about how I’m going to eat for the next three months. But I shouldn’t have to. I should be able to see you at a reasonable price, especially from a mile away.

Signed,

Ryan Ritchie

RTWT

HT: Ed Driscoll.

—————————-

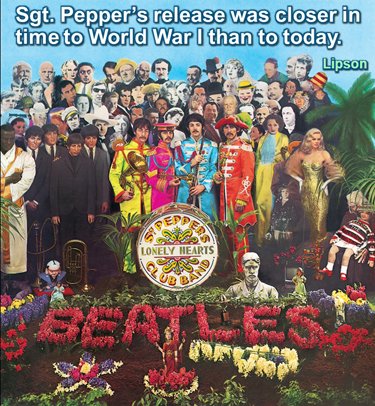

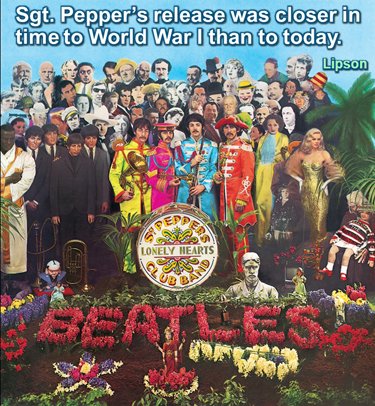

Peter Lay (obviously more of a Stones man) contemplates, and rejects, critical hyperbole extolling the greatness of the Fab Four. They’re pretty darn good at their best. Sergeant Pepper was wildly over-rated. And they do not rank with Schubert.

In his review of The Beatles (aka “The White Album”) published in the Observer in October 1968, the filmmaker Tony Palmer hailed Lennon and McCartney as “the greatest songwriters since Schubert”. The White Album, he insisted, “should surely see the last vestiges of cultural snobbery and bourgeois prejudice swept away in a deluge of joyful music making”.

Palmer was not the first, nor will he be the last, commentator to abandon critical faculties in order to claim a place on the “right side of history”. The previous year Kenneth Tynan declared the release of Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band a “decisive moment in the history of western civilisation”.

There are those who still cling to that claim and, as the gushing response to Peter Jackson’s Get Back, an eight-hour film of salvaged material from the 1969 Let it Be sessions, suggests, the popularity of the Beatles and the affection in which they are held shows no sign of abating. But Palmer’s Schubert comparison is a telling one, not least because The White Album does contain one Schubertian masterpiece: Paul McCartney’s “Blackbird”.

A comment, it is claimed, on the US civil rights struggle, “Blackbird” was inspired by JS Bach’s “Bourée in E minor”, a piece for lute with which McCartney was acquainted. No other song distils his melodic genius down to its purest form and even the lyrics are a notch above the Beatles’s often banal musings.

The problem, apart from the fact that Schubert wrote scores of superior songs, is that The White Album — a double LP which is best edited down to a shortish two-sider — also contains what might be McCartney’s nadir: “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da”, a song of “desperate levity” so hated by the other band members, that they vetoed its release as a single. Its irritatingly ingratiating melody took it to number one anyway, covered by Marmalade.

It’s the pattern with Beatles LPs — that frustrating mixture of the sublime and the ridiculous. Even Revolver — widely regarded as their masterpiece — contains a couple of duffers, courtesy of George Harrison. Similarly, his contribution to The White Album, along with the portentous “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”, is “Piggies”, a grimly twee attack on bourgeois conformity that undermines all the trippy sentiments of peace and love and karma that Harrison preached to his immature end. One is reminded of the Twitter trolls who remind us to “be kind” while spewing misanthropy left, right and centre.

Nowhere is this inconsistency as striking as on Sgt Pepper. Despite its treasures — McCartney’s “She’s Leaving Home”, a heartbreaking narrative of intergenerational misunderstanding set to a rising melody of instant memorability; and “A Day in the Life”, perhaps their finest hour, with verses by Lennon, detached and dreamy (“I’d love to turn you on”) married to McCartney’s jaunty middle section celebrating banality and routine (a psychiatrist could make much of it) — the rest is mediocre: “When I’m Sixty Four”, “Lovely Rita”, “Fixing a Hole”, all fine and dandy, but Schubert? Sgt Pepper has aged horribly in its psychedelic whimsy, especially in comparison with its great contemporary, the Beach Boys’s Pet Sounds. …

30 Jan 2022

People are still turning out appreciative, insightful essays about Peter Jackson’s “Get Back” (2021) 8-hour-long documentary of the Beatles’ 1970 composing sessions leading to a rooftop performance.

Ian Leslie’s substack essay is long, excellent, and definitely worth the read.

There’s a truism in sport that what makes a champion is not the level they play at when they’re in top form but how well they play when they’re not in form. When we meet The Beatles in Get Back, they’re clearly in a dip, and that’s what makes their response to it so impressive. Even the best songs they bring in are not necessarily very good to begin with. Don’t Let Me Down is not up to much at Twickenham. George calls it corny, and he isn’t wrong. But John has a vision of a song that eschews irony and sophistication and lunges straight for your heart, and he achieves it, with a little help from his friends. They keep running at the song, shaping it and honing it, and by the time they get to the roof it is majestic.

The already classic scene in which Paul wrenches the song Get Back out of himself shows us, not just a moment of inspiration, but how the group pick up on what is not an obviously promising fragment and begin the process of turning it into a song. In the days to follow, they keep going at it, day after day, run-through after run-through, chipping away, laboriously sculpting the song into something that seems, in its final form, perfectly effortless. As viewers, we get bored of seeing them rehearse it and we see only some of it: on January 23rd alone they ran it through 43 times. The Beatles don’t know, during this long process, what we know – that they’re creating a song that millions of people will sing and move to for decades to come. For all they know, it might be Shit Takes all the way down. But they keep going, changing the lyrics, making small decision after small decision – when the chorus comes in, where to put the guitar solos, when to syncopate the beat, how to play the intro – in the blind faith that somewhere, hundreds of decisions down the line, a Beatles song worthy of the name will emerge.

A good song or album – or novel or painting – seems authoritative and inevitable, as if it just had to be that way, but it rarely feels like that to the people making it. Art involves a kind of conjuring trick in which the artist conceals her false starts, her procrastination, her self-doubts, her confusion, behind the finished article. The Beatles did so well at effacing their efforts that we are suspicious they actually had to make any, which is why the words “magic” and “genius” get used so much around them. A work of genius inspires awe in a lesser artist, but it’s not necessarily inspiring. In Get Back, we are allowed into The Beatles’ process. We see the mess; we live the boredom. We watch them struggle, and somehow it doesn’t diminish the magic at all. In a sense, Paul has finally got his wish: Let It Be is not just an album anymore. Joined up with Get Back, it is an exploration of the artistic journey – that long and winding road. It is about how hard it is to create something from nothing, and why we do it, despite everything.

RTWT

HT: Karen L. Myers.

11 Jul 2021

From Yale classmate Charlie Lipson.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'The Beatles' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|