Kyoto’s Zen Cuisine

Cuisine, Japan, Kyoto, Shojin, Toshio Tanahashi, Zen

Shiitakes and lily bulbs cloaked in yuba (tofu skin) and served in a kombu broth.

Alex Halberstadt in Saveur:

Writing about the food of Japanese monks and nuns for a magazine like this one presented a conceptual difficulty. From the Buddhist perspective, cooking is a form of spiritual practice that produces nourishment to prepare the body for hard work and meditation. Unlike, say, Memphis barbecue or the cuisine of Lyonnaise bouchons, shojin doesn’t have a whole lot to say on the subject of pleasure. Shojin has bigger fish to fry. Its goals are nothing less than permanent enlightenment, nirvana, the fundamental transformation of the human mind and society. It does not fit easily into the hedonistic, novelty-addled world of food journalism.

Before every other restaurant extolled the virtues of seasonal produce, there was shojin ryori, a Buddhist cuisine reimagined by monk chef Toshio Tanahashi.

I chanced upon my salvation, journalistically speaking, in the person of Toshio Tanahashi. He’d practiced the art of shojin as a Zen monk in a rural temple near Kyoto and then did something unprecedented—he opened a restaurant in Tokyo’s chic Omotesando neighborhood that presented vegan monastic cuisine in a fine-dining context. The restaurant, Gesshin Kyo, became both successful and influential. Reviewing it for the New York Times, author and culinary authority Elizabeth Andoh described it as a “secular space imbued with a spiritual respect for food.†It was a spiritual respect that nonetheless made room for distinctly un-Japanese elements like tomatoes, mangoes, and white bordeaux. Freed from temple kitchens and its role as nourishment, shojin dazzled Tanahashi’s diners with its unfamiliar and subtle beauty. The Zen monk had become a famous chef by reimagining monk food.

Tanahashi closed Gesshin Kyo after 15 years, in 2006. Along the way he wrote two books about shojin ryori and came to see it as a corrective to the world’s restaurant culture, which he believes to be addled with costly, scarce, and unhealthy ingredients. …

[S]hojin [is] world poised between the rigorous simplicity of spiritual practice and its often exquisite trappings. Consider the tools found in a shojin kitchen. On the day we met, Tanahashi brought me to Aritsugu, renowned as a shrine among the international brotherhood of knife fetishists. The family-owned shop has been in continuous operation since 1560 and once supplied swords to the Imperial House of Japan.

At the modern-day shop in Kyoto’s enclosed Nishiki Market, we shimmied past vitrines of eye-wateringly expensive sashimi blades to a back room, where a soft-spoken manager showed us the principal tools of the shojin chef. There was an adorably petite vegetable cleaver called a nakiri-bocho; a one-sided grater of tinned copper trimmed in magnolia wood and deer antler used for working with lotus root and wasabi; and a strainer-ricer made of the braided hairs of a horse’s tail bound with a band of cherry bark. These utensils, made by hand, were remarkably beautiful.

“Things that are made by humans for humans are good for the spirit,†Tanahashi declared. He explained that shojin kitchens forbid plastic and machinery. Taking care of one’s tools, he added, turning the cleaver in his hand, was in itself a form of Buddhist meditation.

Over the next several days, Tanahashi led me on a breakneck tour of shojin—not the grand theory behind it, but the myriad building blocks. He referred to it as my “education.†At an antique lacquerware shop called Uruwashiya, behind one of those dimly lit Kyoto storefronts that always look closed, Akemi Horiuchi, the elegant proprietor, showed us the most important dishes used in serving shojin—several attractively worn red bowls and a matching tray. Red is the auspicious color of the temples, she explained, and the tray’s raised edge indicates that it encloses a sacred space. Shojin must be served in handmade vessels, and few are as painstakingly handmade as these—delicately carved wood covered with layer upon layer of urushi lacquer, making the dishes supple, lightweight, and resilient. The lacquer on the bowls Horiuchi showed us had faded in places—a prized quality, she said—because they were made nearly 500 years ago, in Sen no Rikyu’s lifetime.

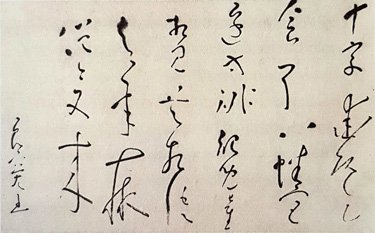

A Zen Death Poem

Calligraphy, Japan, Poetry, Ryonen Genso, Zen

Sixty-six times my eyes

have contemplated the ephemeral spectacle of autumn.

I’ve talked enough about the light

of the moon. Don’t ask me more.

Listen only to the voice of the pines and

of cedars when there is no longer a breath of wind.

The nun RyÅnen GensÅ (1646-1711)

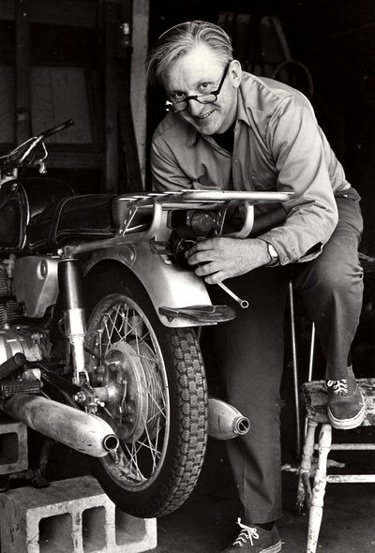

Robert Maynard Pirsig (6 September 1928 – 24 April 2017)

"Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance", Obituaries, Philosophy, Robert M. Pirsig, Zen

Plato’s Chariot Metaphor as sculpture.

Plato, in the Phaedrus, conceives of the soul as having three parts: A rational part (the part that loves truth and knowledge, which should rule over the other parts of the soul through the use of reason). The Charioteer represents man’s Reason. A spirited part (which seeks glory, honor, recognition and victory). The white horse represents man’s spirit (thymos:θÏμος). An appetitive part (which desires food, drink, material wealth and sex). The black horse represents man’s appetites.

Robert M. Pirsig died yesterday.

Recovering from a nervous breakdown, Pirsig, back in the 1970s, crafted a brilliant book memorializing his own deceased former personality (referred to in the third person as “Phaedrus”), and dispensing Buddhistic enlightenment mixed with Plato in the course of a grand road trip. His title was a clever take-off from the 1953 surprise best-seller Zen in the Art of Archery by Eugene Herrigel, a landmark classic in the 1950s Beats’ love affair with Zen.

NPR wrote:

Robert M. Pirsig, who inspired generations to road trip across America with his “novelistic autobigraphy,” Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, died Monday at the age of 88.

His publisher William Morrow & Company said in a statement that Pirsig died at his home in South Berwick, Maine, “after a period of failing health.” …

Zen was published in 1974, after being rejected by 121 publishing houses. “The book is brilliant beyond belief,” wrote Morrow editor James Landis before publication. “It is probably a work of genius and will, I’ll wager, attain classic status.”

Indeed, the book quickly became a best-seller, and has proved enduring as a work of popular philosophy. A 1968 motorcycle trip across the West with his son Christopher was his inspiration.

Christopher Lehmann-Haupt reviewed Zen for The New York Times in 1974. “[H]owever impressive are the seductive powers with which Mr. Pirsig engages us in his motorcycle trip, they are nothing compared to the skill with which he interests us in his philosophic trip,” he wrote. “Mr. Pirsig may sometimes appear to be a greenerâ€America proselytizer, with his beard and his motorcycle tripping and his talk about learning to love technology. But when he comes to grips with the hard philosophical conundrums raised by the 1960’s, he can be electrifying.”

Pirsig was born in Minneapolis, the son of a University of Minnesota law professor. He graduated from high school at 15 and enlisted in the Army after World War II. While stationed in South Korea, he encountered the Asian philosophies that would underpin his work. He went on to study Hindu philosophy in India and for a time was enrolled in a philosophy Ph.D. program at the University of Chicago. He was hospitalized for mental illness and returned to Minneapolis, where he worked as a technical writer and began writing his first book.

A quotation from ZAMM:

That’s all the motorcycle is, a system of concepts worked out in steel. There’s no part in it, no shape in it, that is not out of someone’s mind. …

I’ve noticed that people who have never worked with steel have trouble seeing this—that the motorcycle is primarily a mental phenomenon. They associate metal with given shapes—pipes, rods, girders, tools, parts—all of them fixed and inviolable, and think of it as primarily physical. But a person who does machining or foundry work or forge work or welding sees “steel” as having no shape at all. Steel can be any shape you want if you are skilled enough, and any shape but the one you want if you are not. …

These shapes are all out of someone’s mind. That’s important to see. The steel? Hell, even the steel is out of someone’s mind. There’s no steel in nature. Anyone from the Bronze Age could have told you that. All nature has is a potential for steel. There’s nothing else there. But what’s “potential”? That’s also in someone’s mind!

“I Lived, But”

Japanese Culture, Yasujiro Ozu, Zen

Yasujiro Ozu, Otona no miru ehon – Umarete wa mita keredo [I Lived, But] (1932).

Via Ratak Monodosico.

“Fail Better”

Fail Better, Richard Branson, Samuel Beckett, Silicon Valley, Stanislas Wawrinka, Zen

Mark O’Connell explains, in Slate, how one line buried in one of Samuel Beckett’s obscure modernist works of prose pessimism rather miraculously escaped its confined context to become adopted as a Zen slogan by optimist achievers in Silicon Valley… and on the tennis circuit.

Stanislas Wawrinka’s defeat of Rafael Nadal in the final of the Australian Open last weekend was a milestone not just in the career of a 28-year-old Swiss tennis player but also in the posthumous life of one of the 20th century’s most unswervingly pessimistic writers. This is the first time a Grand Slam title has ever been won by a player with a Samuel Beckett quotation tattooed on his body (barring some unexpected revelation that, say, Ivan Lendl got himself a Waiting for Godot–themed tramp stamp before beating John McEnroe in the 1984 French Open final). The words in question, inked in elaborately curlicued script up the length of Wawrinka’s inner left forearm, are these: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.â€

The quotation is from Worstward Ho, a late, fragmentary prose piece that is one of the most tersely oblique things Beckett ever wrote. But those six disembodied imperatives, from the text’s opening page, have in their strange afterlife as a motivational meme come to much greater prominence than the text itself. The entrepreneurial class has adopted the phrase with particular enthusiasm, as a battle cry for a startup culture in which failure has come to be fetishized, even valorized. Sir Richard Branson, that affable old sage of private enterprise and bikini-based publicity shoots, has advocated from on high the benefits of Failing Better. He breaks out the quote near the end of an article about the future of his multinational venture capital conglomerate, telling us with characteristic self-assurance that it comes “from the playwright, Samuel Beckett, but it could just as easily come from the mouth of yours truly.â€

Hat tips to Steve Bodio and the Dish.

Wawrinka‘s tattoo.

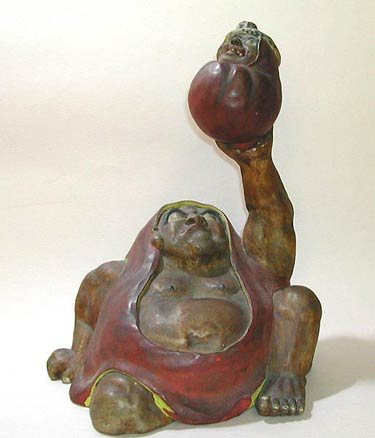

“Nanakorobi Yaoki”

Daruma, Daruma Dolls, Japan, Martial Arts, Zen

A standard cultural artifact in Japan is the darumaoki, the weighted and self-righting tumbler doll painted as a comical caricature of Daruma, aka Bodhidharma, the Buddhist monk who brought Zen (aka Ch’an) Buddhism to China in the 5th century and who founded at the Shaolin Temple the entire tradition of Oriental martial arts.

The dolls are visible embodiments of the Japanese slogan “Nanakorobi Yaoki,” “Seven times down, eight times up,” an admonition encouraging persistence, resilience, and the determination to overcome adversity.

A disgruntled Daruma contemplates with visible dismay his own caricatured form as a darumaoki doll. 19th century ceramic, private collection.

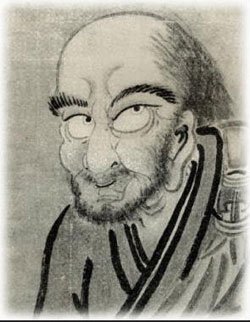

John Roberts, Zen Constitutionalist

Chief Justice John Roberts, John Roberts, Obamacare, US Constitution, Zen

Chief Justice Roberts is kind of like Hakuin, the sort of Zen master who asks you if Obamacare is constitutional, and then whacks you with a shinai if you answer anything but “Moo!”

Chief Justice Roberts, in a manner provocative of keen curiosity, and apparently at the last minute, evolved a new (and extremely Zen) jurisprudential philosophy, urging Supreme Court justices to adopt an extremist philosophy, strangely combining restraint with activism, out of an exaggerated deference to the alleged superior expertise and mandate of Heaven possessed by elected legislators.

Apparently when an elected Congress proceeds to violate the Constitution, according to Mr. Roberts, the good Supreme Court justice will peer skyward, mutter “tsk, tsk” to himself, and proceed to pore closely over the Constitution to find some loophole which can be used to finagle the violative legislative measure into Constitutional legitimacy. He will then wave from afar to the inhabitants of the American Republic, and in his heart wish them the best in capturing total control of both other branches of government, so they can repeal the atrocity.

Protecting Americans from the consequences of their electoral choices, Mr. Roberts explicitly assured us, is not his job.

It is implicitly our job to protect ourselves from having our rights trampled and the Constitution made into a mockery by either winning landslide electoral victories totally repudiating the party currently in power, or possibly by launching a successful armed revolution. And good luck to us, because we certainly are not going to be receiving any help from Mr. Roberts.

Adolph Hitler concluded in 1945 that the German people were demonstrably unworthy of his genius and deserved to lose, and the Russians were really the master race. Mr. Roberts clearly shares this kind of shape-up or ship-out view of Constitutionalism in an electoral democracy. If you lose elections, don’t go crying to Chief Justice Roberts’ Supreme Court. The correct rule is not what the Constitution says, or what the framers had in mind, but the will of the voting electorate as interpreted by the ukases of the successful professional politicians.

Win elections, control Congress and the White House, says Chief Justice Roberts. “There is no ‘try.'”

Russell Kirk Meets BashÅ

Andrew Sullivan, Conservatism, Philosophy, Stewart K. Lundy, Taoism, Zen

Mu Ch’i, Six Persimmons, 13th century, Japan, ink on paper, Daitoku-ji, Kyoto, Japan

Andrew Sullivan, with an air of pious approbation, yesterday linked and quoted an interesting essay by Stewart K. Lundy which proposes to define Conservatism as a form of Zen. It seems a bit odd to me that the perennially agitated and volatile Andrew Sullivan, notorious for combining vehement certainty with rapidly shifting positions, thinks he finds some reflection of his own philosophy or personality in Lundy’s mystical quietism, but there you are.

Mr. Lundy is evidently a neighbor of mine in Loudoun County, Virginia, a senior at Patrick Henry College in Purcellville.

Ignorance is the source of knowledge, silence is the source of noise, and stillness is the source of change. The emptiness of the future provides the possibility for movement. This is the principle of conservatism: preserving not only possibility, but the very possibility of possibilities. This impulse is conservative, but never at the expense of future generations. Conservatism is the art of living.

“The best people have a nature like that of water. They’re like mist or dew in the sky, like a stream or a spring on land. Most people hate moist or muddy places, places where water alone dwells. . . . As water empties, it gives life to others. It reflects without being impure, and there is nothing it cannot wash clean. Water can take any shape, and it is never out of touch with the seasons. How could anyone malign something with such qualities as this.â€

— Ho-Shang Kung in Red Pine’s translation of the Tao Te Ching.

Why the example of water? Water is inherently conservative, conforming to its conditions yet remaining essentially the same. Water prefers stillness. If it is a stream, it runs downhill until it finds a resting place; but it is always in the process of changing, yet it is always only water. In the same way, the essence of conservatism is always the same, even though its conditions constantly change. Were conditions to cease their perpetual flux, conservatism comes to rest as a tranquil pond. The goal of conservatism is tranquility.

In itself, conservatism is tranquil. In relation to the ever-changing human condition, conservatism is always adapting. Conservatism is “formless†like water: it takes the shape of its conditions, but always remains the same. This is why Russell Kirk calls conservatism the “negation of ideology†in The Politics of Prudence. It is precisely the formlessness of conservatism which gives it its vitality. Left alone, the spirit of conservatism is essentially what T.S. Eliot calls the “stillness between two waves of the sea†in “Little Gidding†of his Four Quartets. Conservatism is both like water and the stillness between the waves—the waves are not the water acting, but being acted upon; stillness is the default state of conservatism:

Not known, because not looked for

But heard, half-heard, in the stillness

Between two waves of the sea.

Quick now, here, now, always—

A condition of complete simplicityLike the Greek concept of kairos—acting in the right way, for the right reasons, at the right moment—this sort of waiting is simply careful conservatism. Conservatism is responsive, reactionary, reserved. Conservatism waits. Perhaps this is why conservatism is most needed in the modern age of mobility. Being careful, and above all patient is crucial to doing something right. Realizing that one does not know the best way of doing anything guarantees not that one will find the best way, but that one might not find the worst way. The same principle applies to knowledge: conservatism (hopefully) does not pretend to know the definitive way, but rather professes the virtue of ignorance with the quiet hope of finding knowledge.

Read the whole thing.