Category Archive 'Big Game Hunting'

27 Jul 2025

Found on a bulletin board in the Yale Physics Department fifty-odd years ago.

17 Dec 2023

From the London Spectator:

Hannes became a professional hunter because, as he says in his fine book Strange Tales from the African Bush, he missed “the smell of cordite… the clatter of the helicopters and the memory of the blood brotherhood that few, other than soldiers under fire, are lucky enough to know.” He’s a fourteenth generation white African and a veteran of the famous Rhodesian Light Infantry that fought valiantly in that country’s civil war. He still loves Africa and lives in the Western Cape. When he visited our beach house on the Kenya coast, I managed to persuade him to tell me a few stories, fueled with bottles of Tusker — a much-loved local lager which is named after the elephant that killed the original brewer.

After the civil war, when Rhodesia became Zimbabwe, Hannes tried being a barrister. He tired of life in a courtroom and it wasn’t for him, so he picked up his rifle and headed off back into the bush where he’d grown up and seen so much action. For the next twenty years he hunted across Africa, guiding rich tycoons tracking trophies, but he met his nemesis in the flat dry scrub of northern Tanzania, deep in the heart of buffalo country. Here they came upon a 2,000lb bull at 150 yards. His American client fired his .375 rifle prematurely, as the creature faced him head on, wounding but not killing it. The injured beast took off into a ravine thick with wait-a-bit thorn and combretum scrub.

RTWT

08 Oct 2020

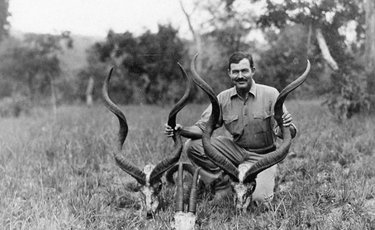

Ernest Hemingway posing with two trophy kudu | Africa, 1934 |

Contemporary British & American newspapers regularly get hold of a photo of a Big Game hunter posing happily with a trophy, and write up him or her as a malevolent monster who sadistically murdered the beautiful, noble, and happy wild critter, who is invariably personalized with a cutsey personal name like “Cecil the Lion.”

Their gullible urban-based readership, who characteristically think that meat grows on supermarket shelves, and that wild animals normally die peaceful deaths in retirement homes, eat up this nonsense and invariably enthusiastically participate in two-minutes of hate. Too many of these people then write checks to phony-baloney Animal Protection Societies (whose officers draw princely salaries and which devote 90% of their budgets to fund-raising) as well as to Anti-Hunting Extremist Organizations.

Hunters are not actually sadists. The hunter appreciates, understands, and cares far more for the hunted animal than the sentimental television watcher or the Animal Rights crackpot. The hunter understands how Nature actually works, and finds powerful emotional and spiritual reward in personal participation in its basic and fundamental process, the contest between the hunter and the game.

“The true trophy hunter is a self-disciplined perfectionist seeking a single animal, the ancient patriarch well past his prime that is often an outcast from his own kind. If successful, he will enshrine the trophy in a place of honor. This is a more noble and fitting end than dying on some lost and lonely edge where the scavengers will pick his bones and his magnificent horns will weather away and be lost forever.”

– Elgin Gates, Trophy Hunter in Asia, 1988.

18 Apr 2019

An interesting old photo of Bill Pinnell, half of the famous Pinnell and Tallifson Kodiak bear guides.

Alaska hunting guide Phil Shoemaker:

This photo was found under his bunk after his passing and the speculation is that it was simply one of his pranks.

Living in the same type of wild country, just across the Shelikov straights from Kodiak, I considered posing a similar scene with one of the old bear skulls we have found and a human skull we found at a WWII airplane wreck.

09 Mar 2019

Rachel Aspden, tattoos and all.

God! how I detest narcissistic, self-important, leftist-conformist scribbling members of the international urban community of fashion. Heads inserted deeply up their fundaments, they go busily around the entire world applying their warped, twisted, and fundamentally wrong aggrieved-victim’s-eye-view of everything, then they insist on telling us all about it, in the process appointing themselves dictators-of-the-universe with every intention of imposing revolutionary change to everything they touch.

This Rachel Apsden is a sort of professional journalist chick, who studied Arabic in Cairo, and who in 2017 published her one big book, Generation Revolution, an account of the failed Arab Spring revolution “from the front line between tradition and change,” as shown through the viewpoints of four young Egyptians.

But, the role of wise, judgmental journalist rooting for change, man! was not enough, evidently. Off goes Rachel to South Africa to enroll in a two-month course qualifying her as a White Hunter/Safari Guide.

I wasn’t a guy, I had no idea how to use a gun, and the only wild dogs anywhere near my own home were part of a research project at London Zoo. But I was learning to change the tires on an old Land Cruiser and memorizing the birth weight of hyena pups because, at thirty-seven, I had burned out. I had just spent several years living in Egypt, reporting on the 2011 revolution and the cruelty and suffering of its aftermath. When I returned to work in the UK, I was angry, heartbroken, and guilty at being able to leave. Though my life in London was safe and easy, as I went through the motions of commuting and sitting in the office, everything felt dark. That was when the dreams began: huge open spaces, empty skies, light—places I’d seen when I’d visited friends in South Africa. That wild nature felt like a lifeline, something I could believe in as an absolute, uncomplicated good, a unifying and healing force that was somehow separate from the moral tangles created by humans. I didn’t think about where these beliefs had come from.

It seems unlikely that she intends to do any Safari guiding though. What this is about is judgmental and condescending tourism with an article in the New York Review of Books, to be followed by the second big book, as the real goal.

Her chief insight seems to have been that her instructors were unconsciously sexist and racist, and unreasonably resentful at finding themselves “at the bottom of the pile” in today’s South Africa.

Rachel knows better. She understands that any White Presence in Africa and Apartheid were terrible Wrongs, and Big Game Hunting a highly questionable part of the Culture of Masculine Machismo and Colonialism. Native Africans were treated unequally. Atonement is due.

“Black Africans just aren’t interested in nature,†a white South African student said, as we sat by the campfire one night. We’d been talking about how dominated the country’s safari industry still was by white people, who owned and managed most of its private reserves, and made up the vast majority of guests. “It’s not PC to say it, but it’s true.â€

Bit by bit, I pieced together the true nature of the land I was hiking and driving over every day. It was an Apartheid-era cattle farm that its owners had designated a game reserve in the 1990s when foot-and-mouth disease made beef farming unprofitable, and the law changed to allow landowners to “ownâ€â€”and therefore benefit from—wildlife. However wild it looked, it was as carefully managed as any London park: the conservation manager showed us his spreadsheets recording the number of animals on the reserve, each species kept in a precise balance with the others in rounds of buying, selling, and culling. As in the Kruger and Botswana’s reserves, elephants, which multiplied quickly thanks to the artificial water sources, posed a problem no one quite knew how to solve.

I admired the reserve owners’ efforts to rewild land that had once been exhausted by intensive farming: uprooting invasive vegetation, reintroducing wildlife, clearing the detritus of old fencing and machinery. This was the story of many South African protected areas (and a reason that some wealthy tourists dismissed the country as “not wild enough,†preferring the remote wildernesses of Zimbabwe and Botswana). But as elsewhere, the land’s human history was obscured. Empty, untouched wilderness was what tourists wanted to see, and this was the illusion the safari industry aimed to recreate.

It wasn’t the only hangover from the days of empire. Guides weren’t simply responsible for providing expert knowledge and ensuring their guests’ safety. They were also expected to administer first aid, mix drinks, change tires, host dinners, clean vehicles, defuse complaints, and assist their guests in every way. Our textbook offered blunt advice on everything from hosting what it called “Oriental clients†(“Do not call the Japanese ‘Chinese’ and vice versaâ€) to dealing with a client’s corpse (“Under no circumstance may the body be transported by the vehicle used for transporting other clientsâ€). Part of our training was to entertain our “guests†on each drive we led, serving up drinks, snacks, and small talk from behind a folding table.

I wondered whether these expectations began to explain the weirdly fluctuating sense of bravado and victimhood that seemed to dog our instructors. Part of it was economic. Guides worked in a luxury industry, but the majority of them were paid very little. A single night at a high-end safari lodge in South Africa could cost $2,000 (including game drives, but excluding French champagne), but the monthly wage of a guide might be less than a quarter of that, with the workers living in basic rooms hidden from the luxurious guest accommodation, working three-week stretches without a break.

Spending your days fixing 4x4s and tracking lions was also a way of avoiding some of the troubling consequences of being a white South African in general, and an Afrikaner in particular. One was the trappings of middle-class life in a high-crime country: the electrified fences and rapid-response signs, guard dogs, window-bars, and lockable internal gates that made me feel caged and edgy when I stayed in Johannesburg or Cape Town. Once past the fortified outer boundary of the game reserve, all these disappeared—along with much of the impact of the Black Economic Empowerment policies that the company official had alluded to, under which non-white South Africans were preferred for most business and employment opportunities. The safari industry, like agriculture and wine farming, had been shaped by historical patterns of land ownership and perceived expertise. At its senior levels, white men still faced little competition.

But the most significant escape, I thought, was probably psychological. In democratic South Africa, to be a member of the minority that had implemented Apartheid was to find yourself in a particular psychic bind. That uncomfortable sense wasn’t one of identity alone: pre-1994 South Africa had made military service compulsory for white young men, and now and again, the older instructors alluded in half-sentences to serving in the army or draft-dodging in small towns along the southern coast.

Although they seemed to have little compunction about the language they used toward others, these men were acutely resentful of even the possibility of being thought racist. When they taught us Zulu or Shangaan animal names, or explained how “local people†harvested honey from mopane trees, I understood that they saw themselves as liberal. And by the standards of the Afrikaner community, which tended to be socially, religiously, and politically conservative, they could well have been right. I thought of the small farming towns I’d driven through in the remote Northern Cape, where everyone seemed to drive Toyota Hilux pickups and listen to Afrikaans country music, and I saw signs for the controversial right-wing pressure group AfriForum, which focused on the ownership of farmland that lay at the heart of Afrikaner national identity. …

Though we had complained both to the staff members themselves and to company management, the behavior and demeanor of the instructors didn’t change, and Dionne and I spoke often about leaving the course. In the end, we resolved to qualify as guides. Perhaps, we thought, we could eventually help to change the industry. After studying and training every day for two months, we took our exams: drawing diagrams of katabatic and berg winds, describing the flagship species of the succulent karoo biome, and discussing the action of neurotoxic venom. Each of us then had to guide a four-hour game drive, with David as our assessor. I sat beside Dionne in the front of the 4×4 as she led her drive; later in the day, she did the same for me. We were both passed as competent to lead 4×4 safaris in dangerous game areas. When we returned to London and New York, both of us submitted detailed written complaints to the company.

RTWT

14 Sep 2015

William Moalosi, a farmer and former hunting guide in Sankuyo, Botswana

The New York Times discovers that the 2004 hunting ban in Botswana is not popular with that country’s villagers.

SANKUYO, Botswana — Lions have been coming out of the surrounding bush, prowling around homes and a small health clinic, to snatch goats and donkeys from the heart of this village on the edge of one of Africa’s great inland deltas. Elephants, too, are becoming frequent, unwelcome visitors, gobbling up the beans, maize and watermelons that took farmers months to grow.

Since Botswana banned trophy hunting two years ago, remote communities like Sankuyo have been at the mercy of growing numbers of wild animals that are hurting livelihoods and driving terrified villagers into their homes at dusk.

The hunting ban has also meant a precipitous drop in income. Over the years, villagers had used money from trophy hunters, mostly Americans, to install toilets and water pipes, build houses for the poorest, and give scholarships to the young and pensions to the old. …

[I]n Sankuyo and other rural communities living near the wild animals, many are calling for a return to hunting. African governments have also condemned, some with increasing anger, Western moves to ban trophy hunting.

“Before, when there was hunting, we wanted to protect those animals because we knew we earned something out of them,†said Jimmy Baitsholedi Ntema, a villager in his 60s. “Now we don’t benefit at all from the animals. The elephants and buffaloes leave after destroying our plowing fields during the day. Then, at night, the lions come into our kraals.â€

Read the whole thing.

06 Aug 2015

Peter Hathaway Capstick was an American travel agent who became so fascinated with Big Game Hunting that he first moved to Africa and became a professional hunter. Capstick then subsequently became one of the all-time most successful writers of blood-curdling accounts of hunting adventures.

Thousands of international commenters accused Dr. Walter Palmer, slayer of “Cecil” the lion, of being a coward. Capstick’s story of one lion charge offers a very different perspective.

In a life of professional hunting one is never short of potential close calls. With most big game, especially the dangerous varieties, one slip can be enough to spend the rest of your life on crutches, if you’re lucky, or place you or sundry recovered parts thereof in a nice, aromatic pine box. Of course, many individual animals stand out in one’s mind or nightmares as having been particularly challenging or having come extra-close to redecorating you. One of the hairiest experiences I have had was with the Chabunkwa lion, a man-eater with nine kills when my gunbearer Silent and I began to hunt him in the Luangwa Valley. We came within waltzing distance of becoming still two more victims.

My mind went over the lion charges I had met before: the quick jerking of the tail tuft, the paralyzing roar, and the low, incredibly fast rush, bringing white teeth in the center of bristling mane closer in a blur of speed. If we jumped him and he charged us, it would be from such close quarters that there would be time for only one shot, if that. Charging lions have been known to cover a hundred yards in just over three seconds. That’s a very long charge, longer than I have ever seen in our thick central African hunting grounds. In tangles like this, a long charge would be twenty-five to thirty yards, which gives you some idea of the time left to shoot.

Ahead of me, Silent stiffened and solidified into an ebony statue. He held his crouch with his head cocked for almost a minute, watching something off to the left of the spoor. The wild thought raced through my skull that if the lion came now, the rifle would be too slippery to hold, since my palms were sweating heavily. What the hell was Silent looking at, anyway?

Moving a quarter of an inch at a time, he began to back away from the bush toward me. I could see the tightness of his knuckles on the knobby, thornwood shaft of the spear. After ten yards of retreat, he pantomimed that a woman’s hand was lying just off the trail and that he could smell the lion. The soft breeze brought me the same unmistakable odor of a house cat on a humid day. Tensely I drew in a very deep breath and started forward, my rifle low on my hip. I was wishing I had listened to mother and become an accountant or a haberdasher as I slipped into a duck-walk and inched ahead.

I was certain the lion could not miss the thump-crash of my heart as it jammed into the bottom of my throat in a choking lump, my mouth full of copper sulphate. I could almost feel his eyes on me, watching for the opportunity that would bring him flashing onto me.

I lifted my foot to slide it slowly forward and heard a tiny noise just off my right elbow. In a reflex motion, I spun around and slammed the sides of the barrels against the flank of the lion, who was in midair, close enough to shake hands with. His head was already past the muzzles, too close to shoot, looking like a hairy pickle barred full of teeth. He seemed to hang in the air while my numbed brain screeched SHOOT! As he smashed into me, seemingly in slow motion, the right barred fired, perhaps from a conscious trigger pull, perhaps from impact, I’ll never know. The slug fortunately caught him below the ribs and bulled through his lower guts at a shallow but damaging angle, the muzzle blast scorching his shoulder.

I was flattened, rolling in the dirt, the rifle spinning away. I stiffened against the feel of long fangs that would be along presently, burying themselves in my shoulder or neck, and thought about how nice and quick it would probably be. Writing this, I find it difficult to describe the almost dreamy sense of complacency I felt, almost drugged.

A shout penetrated this haze. It was a hollow, senseless howl that I recognized as Silent. Good, old Silent, trying to draw the lion off me, armed with nothing but a spear. The cat, standing over me, growling horribly, seemed confused, then bounded back to attack Silent. He ran forward, spear leveled. I tried to yell to him but the words wouldn’t come.

In a single bound, the great cat cuffed the spear aside and smashed the Awiza to the ground, pinning him with the weight of his 450-pound, steel sinewed body the way a dog holds a juicy bone. Despite my own shock, I can still close my eyes and see, as if in Super Vistavision, Silent trying to shove his hand into the lion’s mouth to buy time for me to recover the rifle and kill him. He was still giving the same, meaningless shout as I shook off my numbness and scrambled to my feet, ripping away branches like a mad man searching for the gun. If only the bloody Zambians would let a hunter carry sidearms! Something gleamed on the dark earth, which I recognized as Silent’s spear, the shaft broken halfway. I grabbed it and ran over to the lion from behind, the cat still chewing thoughtfully on Silent’s arm. The old man, in shock, appeared to be smiling.

I measured the lion. Holding the blade low with both hands, I thrust it with every ounce of my strength into his neck, feeling the keen blade slice through meat and gristle with surprising ease. I heard and felt the metal hit bone and stop. The cat gave a horrible roar and released Silent as I wrenched the spear free, the long point bright with blood. A pulsing fountain burst from the wound in a tall throbbing geyser as I thrust it back again, working it with all the strength of my arms. As if brain-shot he instantly collapsed as the edge of the blade found and severed the spinal cord, killing him at once. Except for muscular ripples up and down his flanks, he never moved again. The Chabunkwa man-eater was dead.

Ripping off my belt, I placed a tourniquet on Silent’s tattered arm. Except for the arm and some claw marks on his chest, he seemed to be unhurt. I took the little plastic bottle of sulfathiozole from my pocket and worked it deeply into his wounds, amazed that the wrist did not seem broken, although the lion’s teeth had badly mangled the area. He never made a sound as I tended him, nor did I speak. I transported him in a fireman’s carry to the water, where he had a long drink, and then I returned to find the rifle, wedged in a low bush. I went back and once more put the gunbearer across my shoulders and headed for the village.

Silent’s injuries far from dampened the celebration of the Sengas [a people from southeastern Zambia], a party of whom went back to collect our shirts and inspect the lion. As I left in the hunting car to take Silent to the small dispensary some seventy-five miles away, I warned the headman that if anyone so much as disturbed a whisker of the lion for juju [a charm or amulet], I would personally shoot him. I almost meant it, too. That lion was one trophy that Silent had earned.

The doctor examined Silent’s wounds, bound him, and gave him a buttful of penicillin against likely infection from the layers of putrefied meat found under the lion’s claws and on his teeth, then released him in my care. We were back at the Senga village in late afternoon, the brave little hunter grinning from the painkiller I had given him from my flask.

05 Aug 2015

It has gradually become apparent that reports claiming that “Cecil” was famous in Zimbabwe and some kind of specially beloved lion were simply a fabrication designed to manipulate the public’s emotions.

In reality, Zimbabweans, when asked, reply that they had never heard of “Cecil” and are simply puzzled by all the uproar over the death of one perfectly ordinary lion.

Reuters:

What lion?” acting information minister Prisca Mupfumira asked in response to a request for comment about Cecil, who was at that moment topping global news bulletins and generating reams of abuse for his killer on websites in the United States and Europe. …

For most people in the southern African nation, where unemployment tops 80 percent and the economy continues to feel the after-effects of billion percent hyperinflation a decade ago, the uproar had all the hallmarks of a ‘First World Problem’.

“Are you saying that all this noise is about a dead lion? Lions are killed all the time in this country,” said Tryphina Kaseke, a used-clothes hawker on the streets of Harare. “What is so special about this one?”

As with many countries in Africa, in Zimbabwe big wild animals such as lions, elephants or hippos are seen either as a potential meal, or a threat to people and property that needs to be controlled or killed. …

“Why are the Americans more concerned than us?” said Joseph Mabuwa, a 33-year-old father-of-two cleaning his car in the center of the capital. “We never hear them speak out when villagers are killed by lions and elephants in Hwange.”

———————————————

Goodwell Nzou explains just how ridiculous all this self-indulgent Western sentimentality about lions appears to Africans who actually have experience of living with lions.

So sorry about Cecil.

Did Cecil live near your place in Zimbabwe?

Cecil who? I wondered. When I turned on the news and discovered that the messages were about a lion killed by an American dentist, the village boy inside me instinctively cheered: One lion fewer to menace families like mine.

My excitement was doused when I realized that the lion killer was being painted as the villain. I faced the starkest cultural contradiction I’d experienced during my five years studying in the United States.

Did all those Americans signing petitions understand that lions actually kill people? …

In my village in Zimbabwe, surrounded by wildlife conservation areas, no lion has ever been beloved, or granted an affectionate nickname. They are objects of terror.

When I was 9 years old, a solitary lion prowled villages near my home. After it killed a few chickens, some goats and finally a cow, we were warned to walk to school in groups and stop playing outside. My sisters no longer went alone to the river to collect water or wash dishes; my mother waited for my father and older brothers, armed with machetes, axes and spears, to escort her into the bush to collect firewood.

A week later, my mother gathered me with nine of my siblings to explain that her uncle had been attacked but escaped with nothing more than an injured leg. The lion sucked the life out of the village: No one socialized by fires at night; no one dared stroll over to a neighbor’s homestead.

When the lion was finally killed, no one cared whether its murderer was a local person or a white trophy hunter, whether it was poached or killed legally. We danced and sang about the vanquishing of the fearsome beast and our escape from serious harm.

Recently, a 14-year-old boy in a village not far from mine wasn’t so lucky. Sleeping in his family’s fields, as villagers do to protect crops from the hippos, buffalo and elephants that trample them, he was mauled by a lion and died.

The killing of Cecil hasn’t garnered much more sympathy from urban Zimbabweans, although they live with no such danger. Few have ever seen a lion, since game drives are a luxury residents of a country with an average monthly income below $150 cannot afford. …

The American tendency to romanticize animals … and to jump onto a hashtag train has turned an ordinary situation — there were 800 lions legally killed over a decade by well-heeled foreigners who shelled out serious money to prove their prowess — into what seems to my Zimbabwean eyes an absurdist circus. …

We Zimbabweans are left shaking our heads, wondering why Americans care more about African animals than about African people.

Read the whole thing.

04 Aug 2015

John Derbyshire explicates the two-minutes-of-hate observed all over Western society in honor of Dr. Palmer, the lion-slayer.

[W]hy the massive nationwide hysteria over a lion killed in a remote, badly misgoverned country, under some rather technical issues of local illegality, by a hunter who plausibly was not aware of those issues?

Because, inevitably, the whole incident became refracted through the lens of current public discourse in the U.S.A. into a skirmish in what I call the Cold Civil War: that is, the everlasting struggle between, on the one hand, the Progressive goodwhites who dominate our country’s mainstream culture—the Main Stream Media, the universities and law schools, big corporations, the federal bureaucracy—and, on the other hand, the ignorant gap-toothed hillbilly redneck badwhites clinging to their guns and religion out on the despised margins of civilized society.

Dr. Palmer is, of course, a badwhite. The evidence for this in in his actions. Hunting charismatic megafauna for sport is a thing only badwhites do. Big game trophy hunting is in fact as typically, characteristically badwhite as shopping at Whole Foods, or patronizing microbreweries, or listening to NPR are characteristically goodwhite.

For a full catalog of typical goodwhite lifestyle choices I refer you to Christian Landers’ 2008 book Stuff White People Like—slightly out of date now, but still reliable on most points. I have occasionally entertained the notion of putting out an updated version to be titled Stuff Goodwhites Like, with a companion volume titled, of course, Stuff Badwhites Like. Big game trophy hunting—indeed, hunting of all kinds—would definitely be listed in that latter volume, along with commercial beer, pickup trucks, Protestant Christianity, side-clip suspenders, NASCAR, and other badwhite favorites.

Read the whole thing. Derbyshire’s dissection of Jimmy Kimmel is too good to miss.

29 Jul 2015

“Cecil” the lion.

A series of tear-jerker articles in British newspapers concerning the taking of a lion at the beginning of this month on the outskirts of Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park has unleashed an astonishing tizzy of violent emotionalism and anti-hunting bigotry on the part of the international media’s ill-informed and urban-based mass audience.

Dr. Walter Palmer, a Bloomington, Minnesota dentist who is also a long-time and spectacularly accomplished big game hunter, has been pilloried for effectuating the demise of a mature, 13-year-old male lion, referred to by the Press as “Cecil.” (Wikipedia notes that, typically, “Lions live for 10–14 years in the wild.”) Lions, of course, do not have names.

All the heart-string-tugging malarkey about poor “Cecil” was apparently started by the head of one of those Timothy Treadwell-style, self-appointed, one-man “Save the Charismatic Wildlife By Giving Me Money!” Conservation Charities. Johnny Rodrigues, a Madeira-born former Rhodesian farmer and operator of a failed trucking company, founder and Chairman of the Zimbabwe Conservation Task Force, seems to be the original source of Cecil’s biography and all the complaints.

The story, as told to the BBC, went:

A hunter paid a $55,000 (£35,000) bribe to wildlife guides to kill an “iconic” lion in Zimbabwe, a conservationist has told the BBC.

Allegations that a Spaniard was behind the killing were being investigated, Johnny Rodrigues said.

The lion, named Cecil, was shot with a crossbow and rifle, before being beheaded and skinned, he added.

The 13-year-old lion was a major tourist attraction at Zimbabwe’s famous Hwange National Park.

Zimbabwe, like many African countries, is battling to curb illegal hunting and poaching which threatens to make some of its wildlife extinct.

Mr Rodrigues, the head of Zimbabwe Conservation Task Force, said the use of a bow and arrow heralded a new trend aimed at avoiding arrest.

“It’s more silent. If you want to do anything illegal, that’s the way to do it,” he told BBC’s Newsday programme.

‘Lion baited’

However, the lion, which had a distinctive black mane, did not die immediately and was followed for more than 40 hours before it was shot with rifle, Mr Rodrigues said.

The animal had a GPS collar for a research project by UK-based Oxford University, allowing authorities to track its movements.

Mr Rodrigues said Cecil’s killing was tragic.

“He never bothered anybody. He was one of the most beautiful animals to look at.”

The lion had been “baited” out of the park, a tactic which hunters used to portray their action as legal, Mr Rodrigues said.

Two guides had been arrested and if it was confirmed that the hunter was a Spaniard, “we will expose him for what he is”, he added.

The six cubs of Cecil will now be killed, as a new male lion in the pride will not allow them to live in order to encourage the lionesses to mate with him.

“That’s how it works… it’s in the wild; it’s nature taking its course,” Mr Rodrigues said.

If somebody had fallen out of that Land Rover, it looks to me like “Cecil” would have bothered him.

Mr. Rodrigues was clearly in error on a variety of details.

The hunter was not Spanish, and was actually the American Dr. Palmer. The lion was undoubtedly shot with a longbow, not a crossbow. Dr. Palmer obviously did not bribe anybody. He would have been paying, as is typically required for non-citizens hunting in African countries, per diem for the safari guiding services of a professional hunting company, which would have run something on the order of $1800-2200 a day. (Example: CMS Safaris) He would additionally have paid a $10,000-15,000 trophy fee to the government of Zimbabwe for the privilege of taking a lion.

It is by no means impossible that Mr. Rodrigues is correct as to the total amount of hunting and trophy fees contributed by Dr. Palmer to the Zimbabwean economy and in support of wildlife conservation in that country. Trophy big game hunting is expensive and represents the principal source of revenue in African countries used to protect wildlife and to prevent poaching.

If one looks at the situation correctly, Dr. Palmer was harvesting an aged, trophy lion in exchange for a massive infusion of cash. The ability of African countries to collect those kinds of trophy fees and the ability of sport hunting to provide African employment and to bring that kind of money into the local economy constitutes the best possible kind of motivation for African governments to take a serious interest in the protection, preservation, and survival of big game species. When one lion can bring Zimbabwe $55,000 in cold hard cash, you can bet that lions will not be permitted to be exterminated in Zimbabwe.

The British press stories, based on Mr. Rodrigues’ accusations, claim that the lion was lured outside the park intentionally by baiting, but the later accounts all make clear that “Cecil” wandered out of the park and was shot when found going after bait which had been placed legally to attract leopard. Nobody baits lions, but leopards (absent any other practical method) are typically shot over bait.

Further accusations express outrage that Dr. Palmer shot a collared lion, but “Cecil” was a handsome specimen with a large and very full mane. Looking at two photographs of him, I certainly cannot see a collar. It is obviously unfair to blame the hunter for not seeing a collar buried deep in a lion’s mane.

And, apparently, the harvesting of a collared lion inadvertently by a sport hunter is not unusual. (Telegraph)

The Wildlife Conservation Research Unit at Oxford University has tracked the Hwange lions since 1999 to measure the impact of sport hunting beyond the park on the lion population within the park, using radar and direct observation.

According to figures published by National Geographic, 34 of their 62 tagged lions died during the study period – 24 were shot by sport hunters.

The Press piled on inflammatory details obviously intended to stir readers’ emotions. The newspaper accounts all note that the lion was initially wounded, and then subsequently followed up and killed by gunshot. And then! the poor lion’s remains were outraged and violated. He was skinned and decapitated, the newsprint screams. Urban readers are clearly intended to regard Dr. Palmer and his professional hunter as barbarians on a par with ISIS, running around decapitating lions. Of course, a trophy game animal is commonly skinned and its skull taken and preserved, so that they can be mounted by a taxidermist.

Zimbabwe, of course, is an incompetent and corrupt left-wing kleptocracy run by primitive natives, so all this international brouhaha is provoking exactly the kind of pompous official response one might expect. Dr. Palmer’s lion trophy has been confiscated, and the professional hunting firm is being charged with taking the lion illegally. Zimbabwean authorities now contend that the lion was taken on a farm whose owner had not been allocated any permit allowing a lion to be harvested. If that story is correct, of course, the violation would not be the fault of the American dentist. The visiting hunter pays that $1800-2200 per diem to the professional hunting company precisely so that his White Hunters will guide him to locations where the trophies he is after can be legally hunted and see to it that all of the necessary licenses and permits are in order.

Poor Dr. Palmer, as the result, of all of this has become the object of literally thousands and thousands of pieces of hate postings, many of them explicitly yearning for him to die a painful death, and he has been forced to close his office and go into hiding.

How well do you suppose the safari industry in Zimbabwe will be making out next year? What do you suppose Zimbabwean game license fees funding that country’s conservation revenues are going to be like? As we sit here, you can count on it, letters cancelling next year’s safaris are being written. And it follows inevitably that game protection funding will be down to zip, and poaching and illegal lion taking in the general vicinity of Hwange National Park will be flourishing on an unprecedented scale for many years to come, all thanks to Mr. Rodrigues and all the animal lovers writing news reports for British newspapers.

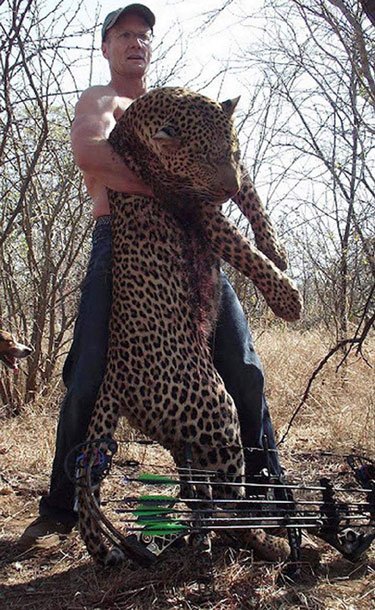

Dr. Palmer with trophy leopard.

08 May 2014

Fox News reports that a Grizzly Bear taken last Fall near Fairbanks by a fellow out hunting moose has broken the Boone & Crockett record.

Larry Fitzgerald and a pal were moose hunting near Fairbanks, Alaska, when they came across fresh bear tracks in the snow. Three hours later, the auto body man had taken down the grizzly that left the prints, an enormous bruin that stood nearly 9 feet tall and earned Fitzgerald a place in the record books.

Although Fitzgerald shot the bear last September, Boone and Crockett, which certifies hunting records, has only now determined the grizzly, with a skull measuring 27 and 6/16ths inches, is the biggest ever taken down by a hunter, and the second largest grizzly ever documented. Only a grizzly skull found by an Alaska taxidermist in 1976 was bigger than that of the bear Fitzgerald bagged.

I’m not really a trophy hunter, or anything,” Fitzgerald, 35, told FoxNews.com. “But I guess it is kind of cool.”

Fitzgerald brought down the bear from 20 yards, with one shot to the neck from his Sako 300 rifle. He said he and hunting buddy Justin Powell knew from the tracks he was on the trail of a massive grizzly, but only learned this week that he held a world record. …

Bears are scored based on skull length and width measurements, and Missouloa, Mont.-based Boone and Crockett trophy data is generally recognized as the standard. Conservationists use the data to monitor habitat, sustainable harvest objectives and adherence to fair-chase hunting rules.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Big Game Hunting' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|