Category Archive 'Supreme Court'

25 Jun 2022

Roger Brooke Taney, Chief Justice of the United States March 28, 1836 — Oct 12, 1864, Author of Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1856).

The post-WWII Conservative Movement’s greatest accomplishment has clearly been elevating jurisprudential reasoning and debate at law schools and the Supreme Court sometimes from the level of “penumbras” and intuitions to a level of serious engagement with the Constitution and the intent of the framers.

Yesterday’s Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, No. 19-1392, 597 U.S deserves to be welcomed and applauded as a victory for the Constitution and the Rule of Law, regardless of one’s views as to desirability of access to abortion.

As a matter of fact, I personally think legal abortion was a good thing practically. Legal abortion was one of the few ways our Society’s policies were eugenic. I think it is hard to dispute that fewer women so wicked, or simply so morally obtuse, as to be willing to kill their own babies, reproducing has to be a Good Thing. Legal abortion undoubtedly also resulted in fewer criminals, fewer people living in dependency on Welfare, and fewer democrat voters. The argument from Utility is all in favor of Abortion.

Desirable as better eugenic outcomes may be, nonetheless, the integrity of our governmental processes and fidelity to the Rule of Law are more important.

The issue of Abortion is a classic instance, resembling a number of major public issues in the past on which the country was deeply, and fairly evenly, divided. The issue of Slavery in the 19th Century was, of course, the classic paradigm issue of the kind.

Justice Blackmun, in Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973), followed the precise example of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney in his Dred Scott decision, by attempting to resolve finally a fractious, painful national quarrel by usurpative judicial fiat.

Supreme Court majorities experience a temptation to assume dictatorial powers precisely in the kinds of rare cases which evoke the deepest national passions and on which the opposing factions are both sufficiently strong as to preclude the near-term victory of either nationally. It is in just such hard cases that partisan Court majorities are prone to step forward highhandedly to try to impose a nation-wide consensus otherwise unachievable.

Dred Scott, predictably, inflamed Abolitionist sentiments in the North and was responded to with Nullification and open resistance. The Dred Scott decision, in fact, played a significant role in deepening the divisions leading ultimately to the Civil War that finally settled the issue of Slavery at the cost of many billions of dollars and the lives of two and a half per cent of the entire national population.

Removing decisions people care about deeply from elected legislatures accountable to the voters and substituting judicial fiat fundamentally violates the democratic process and denies the whole idea of Federalism. We hold elections so voters have the opportunity to express their policy preferences via the choice of their representatives in the legislatures. And the whole point of there being individual states is to allow different local cultures with different opinions and different ideals to make their own rules.

The 20th Century Supreme Court was no more entitled to tell strongly religious states they must countenance Abortion than the 19th Century Supreme Court was to tell citizens of New England and Midwestern states that they must become slave catchers.

Judicial Overreach is highly likely to fail in its intent to resolve a contest permanently. On the contrary, it is much more likely to embitter and more deeply arouse the losers to carry on the battle via electoral politics and thereby it politicizes judicial appointments. Judicial Overreach is inevitably inflammatory and divisive as well as corrosive to the competitive relationship between the rival parties. Just look at what has happened in Senate confirmations of Supreme Court nominees in the decades since Roe was decided.

Roe’s downfall, therefore, is a happy moment in our country’s history, proving thereby that, despite all, the American system of government really can function properly from time to time.

In response to all the caterwalling and references to back alley abortions, one can respond: This isn’t 1922. Safe and reliable birth control is readily available. There is in general no necessity for women to fall back on Abortion.

And, in any event, Abortion laws are obviously going to vary greatly, reflecting the extreme difference, state to state, in culture, religion, and moral opinions. If you want an abortion, you can always hop on a bus and travel to the nearest blue state.

19 May 2022

Larry Tribe.

Isaac Chotiner interviews the Left’s favorite law professor, Larry Tribe, for the New Yorker, seeking his response to the lamentable circumstance of the country finding itself with a conservative, Originalist majority on Supreme Court, an apparent majority perfectly prepared to reverse Roe v. wade.

Larry is obviously not happy.

How has your thinking about the Supreme Court as an institution changed over the past fifty years?

I would say that because I am part of the generation that grew up in the glow of Brown v. Board of Education and of the Warren and Brennan Court, and identified the Court really with making representative government work better through the reapportionment decisions and protecting minorities of various kinds. I saw the Court through rather rose-tinted glasses for a while. As I taught the Court for decades, I came to spend more time on the dark periods of the Court’s history, thinking about how the Court really preserved and protected corporate power and wealth more than it protected minorities through much of our history, and how it essentially gutted the efforts at Reconstruction, and I focussed more on cases like Dred Scott and Plessy v. Ferguson and Korematsu.

And in recent years, as the Court has turned back to its characteristic posture of protecting those who don’t need much protection from the political process but who already have lots of political power, I became more and more concerned about its anti-democratic and anti-human-rights record. I continued to want to make sense of the Court’s doctrines. I wrote a treatise that got very frequently cited around the world and that shaped my teaching about how the Court’s ideas in various areas could be pulled together. But then, after I had done the second edition of that treatise, and it became relied on by a lot of people, I decided [after the first volume] of the third edition, basically, to stop that project.

What were you arguing in the first two editions?

The first was the first effort in probably a hundred years to pull together all of constitutional law. And it led to a rebirth, or flowering, of lots of writing about constitutional law, and writing more focussed on methodology, with different forms of interpretation. I was very excited about that project, and [the second edition] continued it. Most of what I did was to see connections among different areas. I would be writing about commercial regulation, and I would see themes that popped up in areas of civil rights and civil liberties. Or I’d be writing about separation of powers, and I would see problems that arose elsewhere.

And I was always trying to find coherence, because my background in mathematics had led me to be very interested in the deep structures of things. I was working on a Ph.D. in algebraic topology when I rather abruptly shifted from mathematics to law. And so, in my treatise, I developed what I thought of as seven different models of constitutional law. I’m always fascinated by different perspectives and lenses and models. I’ve never thought of law and politics as strictly separate, and efforts by people like Steve Breyer to say that we shouldn’t concede that constitutional law is largely political have always seemed to me to be misleading. That said, I still saw efforts at consistency and concerns about avoiding hypocrisy from the Court. But those things began getting harder to take seriously.

And then Steve Breyer wrote me a long letter saying, “When are you going to finish the third edition of your treatise?” And I wrote him a letter back, which then was published in various places, saying, “I’m not going to keep doing it. And here’s why.” It was a letter that described how I thought constitutional law had really lost its coherence.

At one level, you’re saying something really changed with the Court. But earlier you said that the Court has always had some history of protecting the powerful and not protecting minority rights or the powerless. So did something change, or did the Court just have this brief period, after the Second World War, when you saw it as different before returning to its normal posture?

I think there’s always been a powerful ideological stream, but the ascendant ideology in the nineteen-sixties and seventies was one that I could easily identify with. It was the ideology that said the relatively powerless deserve protection, by an independent branch of government, from those who would trample on them.

Right. The Warren Court was also ideological; it just happened to be an ideology that you or I might agree with.

Exactly. No question. It was quite ideological. Justice Brennan had a project whose architecture was really driven by his sense of the purposes of the law, and those purposes were moral and political. No question about it. I’m not saying that somehow the liberal take on constitutional law is free of ideology. There was, however, an intellectually coherent effort to connect the ideology with the whole theory of what the Constitution was for and what the Court was for. Mainly, the Court is an anti-majoritarian branch, and it’s there to protect minorities and make sure that people are fairly represented. I could identify with that ideology. It made sense to me, and I could see elements of it in various areas of doctrine. But as that fell apart, and as the Court reverted to a very different ideology, one in which the Court was essentially there to protect propertied interests and to protect corporations and to keep the masses at bay—that’s an ideology, too, but it was not being elaborated in doctrine in a way that I found even coherent, let alone attractive.

Maybe I’m wrong about this, but I see more internal contradiction and inconsistency in the strands of doctrine of the people who came back into power with the Reagan Administration and the Federalist Society. I’m not the person to make sense of what they’re doing, because it doesn’t hang together for me. Even if I could play the role that I think I did play with a version that I find more morally attractive, it’s a project that I would regard as somewhat evil and wouldn’t want to take part in.

I’m not trying to paint the picture that says everything was pure logic and mathematics and apolitical and morally neutral in the good days of the Warren Era, and incoherent and ideologically driven in other times. I think that would be an unfair contrast. So I hope what I’ve said to you makes it a little clearer.

You wrote a rather striking piece in The New York Review of Books recently, called “Politicians in Robes,” where you take issue with Breyer essentially still believing that the Court can be apolitical. How should we view the Court now? I think that there is a tendency to say, “These guys are politicians, and they make partisan choices the way anyone else does.”

I guess I think citizens should look at the Court as an inherently political institution, which ideally would, however, offset the aspects of politics in which those who already have power accumulate more of it at the expense of ordinary people and people who are downtrodden or subordinated or subjugated. And people should be critical of the Court when it departs from that function, because then they should say to themselves, “Who are these guys, who essentially were not elected, are independent, are secure and protected? What’s the point of protecting them if they are simply protecting those in power already?” Their independence is of value precisely when they perform an important function: both making democracy work better and protecting those who can’t protect themselves effectively through the political process. People should say to themselves, “When they’re not performing that function, then we really ought not to respect their work and give it a lot of weight.”

Now you or I (unworthy reactionaries that we are) may be inclined to think that the Supreme Court’s job is to interpret the law correctly, strictly in accordance with the Constitution.

Professor Tribe, as we see above, has a completely different theory. In his view, the Supreme Court’s real purpose is to afflict the powerful and enforce, at any cost, the interests of minorities, the “downtrodden or subordinated or subjugated.”

Professor Tribe is indifferent, or actively hostile, to the actual text and meaning of the Constitution, it being obviously in his view the work of dead white males bent only upon protecting the interests of rich white men exactly like themselves.

Professor Tribe’s sympathy for, and emotional identification with, minorities, the poor, and the oppressed, his post-observant-Judaic reflexive Leftism, in his view, apparently rises to a level of significance more worthy of enforcement than the authentic meaning of the Constitution’s text or the intentions of the framers. Pardon me for finding this more than a little intellectually self-indulgent.

More than merely self-indulgent, personally, I tend to look upon the vice-like-grip of representatives of the Elite Gentry Left, like Professor Tribe, upon the cause of “the poor, minorities, and the oppressed,” to be in reality in the nature of a self-interested tactic.

It would obviously be unbecoming for rich fat cats comfortably ensconced in the most prestigious positions in Society to be found asking for greater powers, more privileges, more authority for themselves. The peasants might respond with indignation. But, when, you see, they point to a category of victims, defined specifically as less well off than everybody else, more miserable and more wronged than the rest of all you nobodies, and appoint themselves as the champions and protectors of these lepers and untouchables, it’s a whole new ballgame: the sky’s the limit what they can demand. It’s a very old con game, and a very effective one. That’s why so many play it.

29 Jun 2021

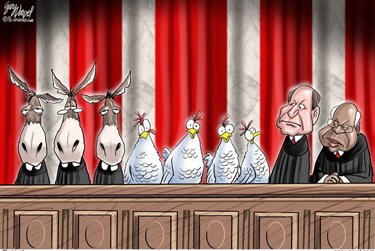

Republicans win the presidency again and again, and Republican presidents battle Senate democrats to get supposedly responsible and conservative nominees confirmed to seats on the nation’s highest court. And it does no good.

Some of those nominees, like Sandra Day O’Connor, David Souter, or Anthony Kennedy, turn out to be liberal Q-boats. Others, like John Roberts and apparently Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch and Amy Coney Barrett, just seem to lack what it takes to hand down decisions the Left seriously doesn’t like.

It is remarkable that a supposedly 6-3 conservative majority court faced with what look like cut-and-dried issues of serious significance, obviously thought about what the establishment media and their liberal friends in Georgetown would have to say, and punted, allowing the Left to win by default.

Case 1: Transgender pride 1, Commonwealth of Virginia girls 0.

The Supreme Court is passing on a key case involving a transgender student, and the ACLU is celebrating the news as an “incredible victory.”

The Supreme Court on Monday declined to hear the case of Gavin Grimm, the transgender student who challenged a Virginia school board’s policy that restrooms are “limited to the corresponding biological genders,” NBC News reports. Lower courts sided with Grimm that this violated Title IX, the civil rights law against sex discrimination, and since the Supreme Court isn’t taking up the case, Grimm’s win stays in place.

Josh Block, an attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union, told NBC that this was “an incredible victory for Gavin and for transgender students around the country,” while Grimm said, “I am glad that my years-long fight to have my school see me for who I am is over. Being forced to use the nurse’s room, a private bathroom, and the girl’s room was humiliating for me, and having to go to out-of-the-way bathrooms severely interfered with my education.”

——————-

Case 2: “Let the People’s Republic of Taxachusetts Reach Across State Lines to Pick New Hampshire Pockets!”

New Hampshire residents working remotely for companies in Massachusetts during the Covid-19 pandemic will still have to pay income tax as if they were commuting to work, after the Supreme Court turned away a challenge to Massachusetts’ rule.

The high court on Monday rejected New Hampshire’s complaint without comment. The justices have exclusive jurisdiction to hear disputes between states if they so choose and such complaints are filed directly with the court.

The dispute centers on a temporary emergency regulation adopted by Massachusetts last year that places a tax on “nonresident income received for services performed” outside of the state.

“For example, the entire salary of a New Hampshire resident who commuted to work full time in Boston in February but has not set foot in the commonwealth for more than eight months continues to be subject to the Massachusetts state income tax as if he were still working every day in Boston,” the complaint states. (Emphasis in original.)

New Hampshire sought a refund of those taxes for its roughly 80,000 residents working remotely for Massachusetts companies. It claims the rule infringes on its “sovereign right to control its own tax and economic policies.” New Hampshire is one of nine states that does not impose an income tax.

I guess the moral is that GOP presidents need to stop nominating justices from the ranks of the “really excellent sheep” top graduates of our most prestigious Ivy League law schools. Republican presidents should start looking for outsider, wild man justices who are serious about defending the Constitution and the culture and who have cojones.

12 Dec 2020

Glenn Reynolds quotes a correspondent:

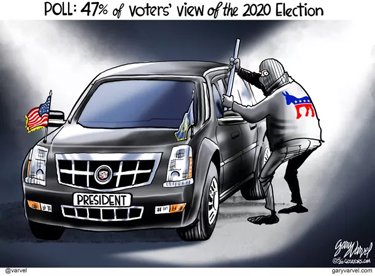

Thought experiment. There are five Democrat justices on the Supreme Court. There was a Democrat president who just ran for reelection. He supposedly lost, but virtually all Democrat voters believe that massive fraud in several Republican controlled states caused him to lose. Many Democrat attorneys general file a lawsuit in the US Supreme Court, essentially identical to the one that is pending now.

Does anyone believe for a second that those five Democrat justices wouldn’t do absolutely anything necessary to make sure the Democrat control of the presidency was maintained? Democrats care about power. Democrats do not care about process, or rules. Now we are being asked to be so meticulous about adhering to the rules, that we are to allow a laughably egregious fraud to succeed, and to permit our own throats to be cut by turning over the executive branch to the people who just committed the biggest political crime in history. I hope five US supreme court justices will show just a tiny bit of the creativity, to put it politely, which Democrat justices had when they, for example, found an imaginary abortion right in the US Constitution. We’ll see what happens.

and adds himself:

People always take for granted that the liberal justices will stick together, and rule for the Democrats. Even Democrats take that for granted.

06 Nov 2020

The democrats are busily harvesting ballots and the MSM has awarded Pennsylvania to Biden, but it’s not actually over, ’til it’s over.

Alexander Macris explains that there is a very major problem here: the democrat-controlled Pennsylvania Supreme Court went ahead and blithely violated the US Constitution, and when Donald Trump appeals and that appeal goes to the US Supreme Court, he’s got a winning argument.

In 2019, the PA legislature passed a law called Act 77 that permitted all voters to cast their ballots by mail but (in Justice Alito’s words) “unambiguously required that all mailed ballots be received by 8 p.m. on election day.†The exact text is 2019 Pa. Leg. Serv. Act 2019-77, which stated: “No absentee ballot under this subsection shall be counted which is received in the office of the county board of elections later than eight o’clock P.M. on the day of the primary or election.†I agree with Justice Alito: That is unambiguous.

Act 77 also provided that if this portion of the law was invalidated, that much of the rest of Act 77, including its liberalization of mail-in voting, would also be void. The exact text is: “Sections 1, 2, 3, 3.2, 4, 5, 5.1, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 12 of this act are nonseverable. If any provision of this act or its application to any person or circumstance is held invalid, the remaining provisions or applications of this act are void.â€

To again put this into common English, the Pennsylvania legislature passed a law that said mail-in ballots had to arrive by 8PM on election day to be counted, and then said that if the Court over-ruled that law, the entire law that permitted mail-in ballots was invalid.

In the face of this clear text, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, by a vote of four to three, made the following decrees, summarized here by SCOTUS:

Mailed ballots don’t need to be received by a election day. Instead, ballots can be accepted if they are postmarked on or before election day and are received within three days thereafter. Note that this is directly contravenes the text above.

A mailed ballot with no postmark, or an illegible postmark, must be regarded as timely if it is received by that same date.

In doing so, PAs’ high court expressly acknowledged that “the statutory provision mandating receipt by election day was unambiguous†and conceded the law was “constitutional,†but still re-wrote the law because it thought it needed to do so in the face of a “natural disaster.†It justified its right to do so under the Free and Equal Elections Cause of the PA State Constitution. …

There is a strong likelihood that the State Supreme Court decision violates the Federal Constitution. Justice Alito writes: “The provisions of the Federal Constitution conferring on state legislatures, not state courts, the authority to make rules governing federal elections would be meaningless if a state court could override the rules adopted by the legislature simply by claiming that a state constitutional provision gave the courts the authority to make whatever rules it thought appropriate for the conduct of a fair election.â€

Justice Alito is referring to the following clauses of the US Constitution:

Art. I, §4, cl. 1, which states “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof.â€

Art. II, §1, cl. 2, which states “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.â€

Again, translating this into common English, the US Constitution grants state legislators the exclusive right to prescribe the time, place, and manner of holding elections, and to direct the appointment of the electors.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court didn’t just say “Act 77 is unconstitutional.†It re-wrote Act 77 itself, by judicial fiat, creating new rules for time, place, and manner, of holding elections. In doing so, the State Supreme Court violated the US Federal Constitution.

And that’s the real case here. The US Supreme Court is going to rule that the State Supreme Court violated the US Constitution, the State Supreme Court’s ruling is going to be overturned, and the votes that arrived after 8 PM on election day will be discarded. On that basis, Trump will win Pennsylvania.

RTWT

24 Sep 2020

Glenn Reynolds points out very astutely that, if the Supreme Court were genuinely representative of the country, instead of a small, and currently intensely abberant elite cultural clique, and if the Court had properly limited itself to interpreting the Law, rather than following the grand Dred Scott tradition of exploiting an ephemeral Court majority to settle intensely divisive national issues by judicial fiat, we wouldn’t have the vicious political struggle over Supreme Court appointments that has become the norm in recent years.

The power of playing the decisive Platonic Guardian card and getting your way permanently is too valuable a prize.

Why does Justice Ginsburg’s replacement matter so much that even “respectable†media figures are calling for violence in the streets if President Trump tries to replace her? Because the Supreme Court has been narrowly balanced for a while, with first Justice Anthony Kennedy, and later Chief Justice John Roberts serving as a swing vote. Ginsburg’s replacement by a conservative will finally produce a long-heralded shift of the Supreme Court to a genuine conservative majority.

That shift matters because, for longer than I have been alive, all sorts of very important societal issues, from desegregation to abortion to presidential elections and state legislative districting — have gone to the Supreme Court for decision. Supreme Court nominations and confirmations didn’t used to mean much — Louis Brandeis was the first nominee to actually appear before the Senate Judiciary Committee — because the Court, while important, wasn’t the be-all and end-all of so many deeply felt and highly divisive issues. Now it very much is.

The point isn’t whether the Court got the questions right. The point is that it decided these important issues and, having done so, took them off the table for democratic politics. When Congress decides an issue by passing a law, democratic politics can change that decision by electing a new Congress. When the Court decides an issue by making a constitutional ruling, there’s no real democratic remedy.

That makes the Supreme Court, a source of final and largely irrevocable authority that is immune to the ordinary winds of democratic change, an extremely important prize. And when extremely important prizes are at stake, people fight. And get hysterical.

Almost as bad, the Court is highly unrepresentative. That doesn’t matter when it’s deciding technical legal issues, but once it starts ruling on social issues of sweeping importance to all sorts of Americans, its lack of diversity becomes a problem. And not just the usual racial and gender diversity. Every current member of the Court is a graduate of Harvard or Yale Law Schools. (Justice Ginsburg offered a bit of diversity there, having spent her third year, and gotten her degree from, that scrappy Ivy League upstart, Columbia University. But she spent her first two years at Harvard). All of them were elite lawyers, academics, or appellate judges before arriving on the Court. They are all card-carrying credentialed members of America’s elite political class. Which, as I mentioned earlier, is in general pretty terrible.

Justices used to come from much more diverse backgrounds. Until well into the 20th Century, many Justices — Justice Robert Jackson was the last — didn’t have law degrees, having “read law†after the fashion of Abraham Lincoln, and for that matter pretty much every lawyer and judge until the 20th Century. Many had been farmers, military officers, small (and large) businessmen, even in one case an actuary. But now they are all, in Dahlia Lithwick’s words, “judicial thoroughbreds†with very similar backgrounds, backgrounds that make them very different from most Americans, or even from most lawyers.

So to break it down: All the hysteria about a Ginsburg replacement stems from the fact that our political system is dominated by an allegedly nonpolitical Court that actually decides many political issues. And that Court is small (enough so that a single retirement can throw things into disarray) and unrepresentative of America at large.

RTWT

24 Sep 2020

In the liberal stronghold of the Atlantic, Minnesota Law Professor Alan Z. Rosenshtein warns his fellow lefties that the time of liberal goals being legislated from the bench is drawing to an inevitable close.

[T]he Warren and early Burger Courts painted a vivid, alluring picture of what justice by judiciary could look like. And even if liberals understood, deep down, that those two decades were an aberration in American legal history, the Court has given them just enough victories since then to keep the dream alive. For lawyers and law professors, there is also the simple matter of professional vanity: If the Supreme Court is the vanguard of American justice, then judges, and thus the lawyers who argue before them and the scholars who analyze (and, when necessary, chastise) them, are the nation’s most important profession—the priests and elders of the civic religion that is American constitutionalism.

Fundamentally, though, many liberals loved the Supreme Court for the same reason they loved the law: a vision of universal harmony and justice brought about by reason and persuasion, not the brute forces of political power. Victory in the political arena is always incomplete and uncertain, not to mention grubby. Politics appeals to our baser instincts of greed and fear and competition—which, of course, is why it is so powerful. By contrast, law—whether through “neutral principles†or “reasoned elaboration†or elaborate moral theories, to name a few of the core organizing ideas of 20th-century legal theory—holds out the promise of something objective, something True. To win in the court of the Constitution is to have one’s view enshrined as just, not only for today but with the promise of all time.

But eventually liberals lost faith that the Court would interpret the Constitution in their favor. What started as a trickle of disillusionment grew throughout the 1980s and ’90s and became a torrent when Roberts became chief justice in 2005 and led the conservative wing to undermine a number of liberal legal priorities, from gun control to campaign-finance law to voting rights. Although many liberal lawyers still dutifully fight in federal court to protect rights where they can, they do so with the increasing understanding that they are simply delaying the inevitable. And legal scholars have gradually given up on the Court as a guarantor of constitutional values, advancing theories of popular constitutionalism or progressive federalism to serve as a counterweight to the Court’s conservative transformation. Whatever was left of the Court’s sacred aura as above partisan politics was ripped away by Mitch McConnell’s denial of a vote to Merrick Garland in 2016 and the bitterness of the confirmation hearings over Brett Kavanaugh two years later.

The clearest sign that many liberals are giving up their remaining idealism about the Court is that, for many moderate Democrats (not to mention those on the progressive left), court packing has gone from a fringe theory to not just a viable option but a moral imperative if Joe Biden wins in November and the Democrats take back the Senate.

RTWT

18 Sep 2019

John Kass explains, in the Chicago Tribune, now that Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s pancreatic cancer is back in the news, the Left is panicking that its loss of control of the Supreme Court will be lengthened and reinforced, and some of its stolen culture war victories may be reversed.

The strategy of the left is undeniable and clear. It is about the use of force, about relentless pressure and shame, using media as both handmaiden and the lash. It is about those who virtue signal most often about due process, demanding it, yet denying those same due process considerations to those with whom they disagree.

The left’s end game is the delegitimization of the Supreme Court, if justices don’t give them the political outcomes they can’t achieve through legislation.

One way to accomplish this is to sear into the American mind the idea that Kavanaugh is personally illegitimate, and therefore, his reasoning and decisions are illegitimate. Though the allegations against him remain uncorroborated, and most are incredible and fall apart in embarrassing fashion, like the one most recently in the Times, the assault continues.

And not only against Kavanaugh, but also against other justices and future nominees. They are warned that destruction and humiliation await.

So, the left would hang upon his neck an asterisk like some medal of shame, a reminder to future history that everything he accomplishes is illegitimate.

RTWT

13 Jul 2018

Business Insider points out that Trump may just be getting started on remodeling the Supreme Court.

Trump now stands to secure two justices in the first half of his first term. Presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush appointed two justices each during their eight years in office.

Supreme Court justices, who serve for life after a presidential appointment and Senate confirmation, represent one of the longer-lasting marks a president can leave on the country, as the justices often serve for decades.

But Trump reportedly thinks he can get an additional two justices in.

In October, the news website Axios cited an anonymous source detailing private predictions by Trump that Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor would retire during his term.

“What does she weigh? 60 pounds?” Trump asked of the now-85-year-old Ginsburg, a source told Axios. The same report indicated Trump said Sotomayor, over 20 years younger than Ginsburg, was also in trouble because of “her health.”

“No good. Diabetes,” Trump reportedly said.

Sotomayor had a health scare in January with paramedics treating her for low blood sugar, but she quickly returned to work. Sotomayor says she’s vigilant about her Type 1 diabetes, which she’s had since childhood.

During the 2016 campaign, Trump often said he or his Democratic opponent, Hillary Clinton, could end up appointing five justices. …

Ginsburg and Sotomayor are liberal justices, so replacing both Kennedy and either of them with conservatives could change the court’s makeup for decades, possibly reversing decisions like Roe v. Wade.

RTWT

30 Jun 2018

Bill Jacobson explains why they are taking it so hard:

There’s a reason the left is freaking the hell out over the Kennedy retirement. The federal district and appeals courts have been the principal vehicles for achieving liberal political gains that could not be gained at the ballot box or through congressional elections. The Supreme Court, usually by a one-vote Kennedy margin (with the exception of Obamacare, where Roberts defected), also has served that role in fewer, but the most important, cases.

We are used to losing institutions. The left is not. They are waking up to the possibility that the judiciary may be restored to the neutral role it should play, and would no longer serve as a liberal super-legislature.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Supreme Court' Category.

Feeds

|