Category Archive 'Meritocracy'

15 Jul 2016

This is the Meritocracy?

Helen Andrews casts a jaundiced look at The New Ruling Class in Hedgehog Review.

Meritocracy began by destroying an aristocracy; it has ended in creating a new one. …

Not since the Society of the Cincinnati has a ruling elite so vehemently disclaimed any resemblance to an aristocracy. The structure of the economy abets the elite in its delusion, since even the very rich are now more likely to earn their money from employment than from capital, and thus find it easier to think of themselves basically as working stiffs. As cultural consumers they are careful to look down their noses at nothing except country music. All manner of low-class fare—rap, telenovelas, Waffle House—is embraced by what Shamus Rahman Khan calls the “omnivorous pluralism†of our elite. “It is as if the new elite are saying, ‘Look! We are not some exclusive club. If anything, we are the most democratized of all groups.’â€

Khan’s Privilege: The Making of an Adolescent Elite at St. Paul’s School is a fascinating document, because he seems to have been genuinely surprised by what he found when he returned to his old boarding school to teach for a year. Khan, the grandson of Irish and Pakistani peasants, worked his way to a Columbia University professorship in sociology via St. Paul’s and Haverford College. So he thought he knew meritocrats—but today’s breed gave him a bit of a fright. For one thing, they proved to be excellent haters. Consider how they talk about a legacy student whose background can be inferred from the pseudonym Khan gives him, “Chase Abbottâ€:

After seeing me chatting with Chase, a boy I was close with, Peter, expressed what many others would time and again: “that guy would never be here if it weren’t for his family.… I don’t get why the school still does that. He doesn’t bring anything to this place.†Peter seemed annoyed with me for even talking with Chase. Knowing that I was at St. Paul’s to make sense of the school, Peter made sure to point out to me that Chase didn’t really belong there.… Faculty, too, openly lamented the presence of students like Chase.

“Openly lamentedâ€! Poor Chase. This hatred is out of all proportion to the power still held by the Chases of the school, which is almost nil. Khan discovers that the few legacy WASPs live together in a sequestered dorm, just like the “minority dorm†of his own schooldays, and even the alumni “point to students like Chase as examples of what is wrong about St. Paul’s.†No, the hatred of students like Chase feels more like the resentment born of having noticed an unwelcome resemblance. It is somehow unsurprising to learn that Peter’s parents met at Harvard.

Of course, Peter is not at St. Paul’s because his parents went to Harvard; as he makes clear to Khan, he is there because of his hard work and academic achievement. Here we have the meritocratic delusion most in need of smashing: the notion that the people who make up our elite are especially smart. They are not—and I do not mean that in the feel-good democratic sense that we are all smart in our own ways, the homely-wise farmer no less than the scholar. I mean that the majority of meritocrats are, on their own chosen scale of intelligence, pretty dumb. Grade inflation first hit the Ivies in the late 1960s for a reason. Yale professor David Gelernter has noticed it in his students: “My students today are…so ignorant that it’s hard to accept how ignorant they are.… [I]t’s very hard to grasp that the person you’re talking to, who is bright, articulate, advisable, interested, and doesn’t know who Beethoven is. Had no view looking back at the history of the twentieth century—just sees a fog. A blank.†Camille Paglia once assigned the spiritual “Go Down, Moses†to an English seminar, only to discover to her horror that “of a class of twenty-five students, only two seemed to recognize the name ‘Moses’.… They did not know who he was.â€

Hat tip to The Barrister.

02 Jul 2013

Alex Mayyasi tells us all about the IIT Entrance Exam.

The admissions test for the Indian Institutes of Technology, known as the Joint Entrance Examination or JEE, may be the most competitive test in the world. In 2012, half a million Indian high school students sat for the JEE. Over six grueling hours of chemistry, physics, and math questions, the students competed for one of ten thousand spots at India’s most prestigious engineering universities.

When the students finish the exam, it is the end of a two plus year process. Nearly every student has spent four hours a day studying advanced science topics not taught at school, often waking up earlier than four in the morning to attend coaching classes before school starts.

The prize is a spot at a university that students describe without hyperbole as a “ticket to another life.†The Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) are a system of technical universities in India comparable in prestige and rigor to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology or the California Institute of Technology. Alumni include Sun Microsystems co-founder Vinod Khosla, co-founder of software giant Infosys Narayana Murthy, and former Vodafone CEO Arun Sarin. Popular paths after graduation include pursuing MBAs or graduate degrees at India’s and the West’s best universities or entertaining offers from McKinsey’s and Morgan Stanley’s on-campus recruiters.

Government subsidies make it possible for any admitted student to attend IIT. The Joint Entrance Exam is also the sole admissions criteria – extracurriculars, personal essays, your family name, and, until recently, even high school grades are all irrelevant. The top scorers receive admission, while the rest do not.

This means that the test can vault students from the lowest socioeconomic background into the global elite in a single afternoon. Entire families wait outside the test center, as involved in the studying and test process as the children they pin their hopes on. In extreme cases, parents have sold their land to pay tutors to coach their children for the JEE.

Only two percent of students will be rewarded for their hard work. In 2012, Harvard accepted 5.9% of applicants. Top engineering schools MIT and Stanford had acceptance rates of 8.9% and 6.63%. The acceptance rate at the IITs, as represented by the pass rate in the JEE, was 2%. Every year, when the results are announced and the media swarms the accepted students, 490,000 students receive disappointing news.

You sit in a room with hundreds of test takers and look around and smile because, personally, you enjoy these kinds of tests, and besides, you have a private contest going with yourself. You mean to try to be finished with the test before anybody else, so that you can stand up, hand in the answer sheet, and theatrically leave, with dozens of eyes looking on at you with hatred.

Hat tip to the Dish.

17 Feb 2013

The Berkeley College Dining Hall at Yale

The Yale Daily News recently did a feature exploring what life is like for meritocratic recruits from financially disadvantaged backgrounds at Yale.

MacBooks. Dooney & Bourke bags. MoMA and the Met. These were the things that [she didn’t have, that Shanaz Chowdhery ’13] says, set her apart.

It didn’t take long for [her] to notice that people were different at Yale. “There was all this cultural capital that people seemed to have,†she says.

Where she was from, no one read The New Yorker on Sundays.

The differences weren’t just cultural, either: Chowdhery recalls her shock at seeing girls walking around campus with $100 handbags.

After she noticed that so many students here used Macs, she says, she looked up the price and couldn’t believe her eyes. Her classmates were lounging on Old Campus with $2,000 laptops.

Chowdhery’s father put her generic Windows laptop on a credit card. She believes he was paying it off her entire freshman year.

Even after being admitted, many students from lower-income backgrounds feel socially aloof from their wealthier classmates.

For Leonard Thomas ’14, feelings of difference and isolation were the largest obstacles to overcome as he transitioned from life in Detroit to being a student at Yale. “I felt poor here,†he says. “I didn’t necessarily feel poor in Detroit because I wasn’t the extreme case.

“I’m an extreme case of poverty here.â€

David Truong ’14 still remembers what it was like to move into his freshman dorm. As he watched a suitemate buy a TV stand, a TV and an Xbox without hesitation, he cringed while paying for clothes hangers and plastic storage bins for his room. That first weekend when everyone was getting to know each other, Truong struggled with suite discussions about splitting the cost of a couch. The expectation that everyone would be contributing to the cost of furnishing the suite, while he thought it fair, was an adjustment.

That expectation of spending does not disappear after move-in weekend. Jennifer Friedmann ’13 says that Yale has a “culture around money.†“You were expected to be able to go out to dinner,†she said. “If I had a coffee date with someone, it was expected that everyone was buying coffee and that it wasn’t a financial burden for anyone.†But Friedmann did not want the fact that she was on financial aid to interfere with her ability to socialize with anyone on campus, regardless of socio-economic background. By shopping at thrift stores, she says she found it more feasible to “be a social person on this campus without making people feel weird about me being on financial aid.â€

———————–

I can remember friends of mine doing the thrift shop thing, and sometimes finding some really excellent Harris Tweed sport coats at derisory prices, back during the Cretaceous Period, when I was at Yale.

I grew up in an economically-depressed mining town in Northeastern Pennsylvania and got a full scholarship to Yale, so I’m personally quite well acquainted with the kind of experiences described in the Yalie Dailey’s feature.

I was well-insulated from social insecurity by personal arrogance and family pride, but financially I was a total idiot. I had never previously had a checkbook, and the Yale Coop presented you on arrival as a freshman with a credit card (and access to a store full of books and records).

My approach to poverty at Yale was to join in happily with the revels of my more-affluent classmates and perhaps even to cut a bit more of a dash than some of those. Like Mr. Micawber, I assumed all that financial stuff would work itself out somehow or other. However, the dour Puritan prep school regime extended onward into college life in those days, and fiscally-irresponsible black sheep like myself faced unlimited possible forms of vengeance at the hands of their residential college deans.

Inevitably, I found myself, before long, out of Yale, back in Pennsylvania in disgrace, and now classified 1-A by Richard Nixon’s draft board.

When I returned to Yale, several years later, I accidentally became involved in operating a successful film society, which happily provided me with the kind of income I needed to survive.

The Yale Daily News, I think, is basically correct in noting that naive and immature adolescents from extremely provincial backgrounds, however talented, are going to run into some real adaptation issues if they decide to accept the gold-engraved invitation to jump into the great big pond of elite university education, and not everyone will adapt.

I was one of six meritocratic Yale admissions accepted into a special Early Concentration in Philosophy program. Of our six oh-so-gifted young men, four got kicked out of Yale. Two of the four were eventually re-admitted. The other two never came back, and have never been heard from by the rest of us again. There has always been a pretty high casualty rate in the meritocracy.

———————–

And, speaking of finances and Ivy League schools, Brown, it seems, is now charging $57,232 plus a bunch of add-on fees. Whew!

But, hey! Sex change operations and nudity workshops come with that.

Hat tip to the Barrister.

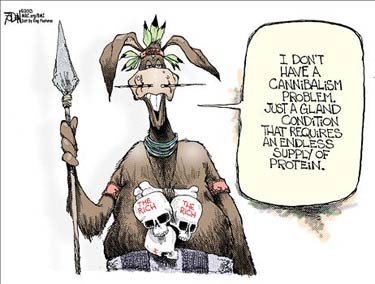

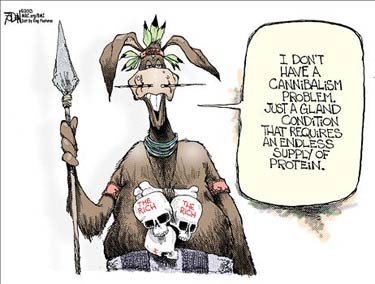

25 Jan 2013

Walter Russell Mead describes the democrat elite’s vision of the future: a massive system of redistributionism devoted to trickling down condescending alms to a nation of losers from a tiny meritocratic New Class elite which rules over all.

A conventional, widely shared view informs the way that blue America looks at that future. This view holds that the death of industrial society means the death of the mass middle class. When millions of people can’t make a living “making stuff†in factories anymore, wages for the unskilled will fall. America will be increasingly polarized between a small group of high skilled creative professionals and a larger group scavenging a living by serving them: mowing their lawns, catering their parties and so on.

Those who think that the blue model needs to be preserved and extended into the future (including, I think, our current president and most of his top allies and advisors), tend to think that under those conditions we will both need and be able to afford an ever-more active redistributive state. The tycoons and the very successful minority will be so rich, thanks to their continuing gains from globalization and technological change, that they can pay progressively higher taxes to fund basic services and middle class jobs for enough of the rest of the country that something like a middle class society can be preserved. From this perspective, a government-funded health care system is more than a method of delivering health care: it is a way of providing protected, blue-model type jobs when the factories have mostly disappeared.

Read the whole thing.

14 Jul 2012

David Brooks is just one of several writers recently identifying the character of our contemporary elite as a grave problem, and he has a theory about the source of members of the modern meritocratic elite’s extreme sense of self-entitlement and personal exemption from any and all rules and standards.

The corruption that has now crept into the world of finance and the other professions is not endemic to meritocracy but to the specific culture of our meritocracy. The problem is that today’s meritocratic elites cannot admit to themselves that they are elites.

Everybody thinks they are countercultural rebels, insurgents against the true establishment, which is always somewhere else. This attitude prevails in the Ivy League, in the corporate boardrooms and even at television studios where hosts from Harvard, Stanford and Brown rail against the establishment.

As a result, today’s elite lacks the self-conscious leadership ethos that the racist, sexist and anti-Semitic old boys’ network did possess. If you went to Groton a century ago, you knew you were privileged. You were taught how morally precarious privilege was and how much responsibility it entailed. You were housed in a spartan 6-foot-by-9-foot cubicle to prepare you for the rigors of leadership.

The best of the WASP elites had a stewardship mentality, that they were temporary caretakers of institutions that would span generations. They cruelly ostracized people who did not live up to their codes of gentlemanly conduct and scrupulosity. They were insular and struggled with intimacy, but they did believe in restraint, reticence and service.

Today’s elite is more talented and open but lacks a self-conscious leadership code. The language of meritocracy (how to succeed) has eclipsed the language of morality (how to be virtuous). Wall Street firms, for example, now hire on the basis of youth and brains, not experience and character. Most of their problems can be traced to this.

If you read the e-mails from the Libor scandal you get the same sensation you get from reading the e-mails in so many recent scandals: these people are brats; they have no sense that they are guardians for an institution the world depends on; they have no consciousness of their larger social role.

07 Nov 2011

Helmuth Karl Bernhard Graf von Moltke (1800-1891)

Ross Douthat, I think, rather laboriously reaches the same conclusion Count von Moltke reached long ago, but Douthat miscategorizes the offenders.

In hereditary aristocracies, debacles tend to flow from stupidity and pigheadedness: think of the Charge of the Light Brigade or the Battle of the Somme. In one-party states, they tend to flow from ideological mania: think of China’s Great Leap Forward, or Stalin’s experiment with Lysenkoist agriculture.

In meritocracies, though, it’s the very intelligence of our leaders that creates the worst disasters. Convinced that their own skills are equal to any task or challenge, meritocrats take risks than lower-wattage elites would never even contemplate, embark on more hubristic projects, and become infatuated with statistical models that hold out the promise of a perfectly rational and frictionless world. (Or as Calvin Trillin put it in these pages, quoting a tweedy WASP waxing nostalgic for the days when Wall Street was dominated by his fellow bluebloods: –Do you think our guys could have invented, say, credit default swaps? Give me a break! They couldn’t have done the math.–)

Field Marshall von Moltke conceptually divided his officers into a four part matrix:

— Smart & Lazy: I make them my Commanders because they make the right thing happen but find the easiest way to accomplish the mission.

— Smart & Energetic: I make them my General Staff Officers because they make intelligent plans that make the right things happen.

— Dumb & Lazy: There are menial tasks that require an officer to perform that they can accomplish and they follow orders without causing much harm

— Dumb & Energetic: These are dangerous and must be eliminated. They cause thing to happen but the wrong things so cause trouble.

In which category, do Ross Douthat’s meritocrats really belong? It seems obvious to me.

Douthat has the precise same problem our contemporary “meritocracy” has: mistaking credentials and narrowly focused technical expertise for intelligence. In reality, the meritocratic system of education rewards energy and proficiency in areas requiring certain kinds of intellectual ability almost entirely divorced from wisdom, integrity, and good judgment. What our system of education characteristically produces are skilled sophists and opportunists, most conspicuously ingenious in conformity. It is a system designed to promote the energetic but stupid.

19 Sep 2011

There has been a fair amount of comment in certain alumni circles about the latest Ivy League kerfuffle: Harvard University’s effort, at the beginning of this year’s Fall Term, to “encourage” freshmen to sign a kindness pledge.

Harvard’s new initiative provoked some serious criticism noting that students were likely to feel pressured to sign (as a copy of the pledge with each student’s name and a space for a signature was placed hanging in each entryway), but Harvard then apologized and retreated (being so nice, after all).

Not surprisingly, the incident produced a good deal of coverage, and some mockery.

Ross Douthat (who attended the little school in Cambridge) responded to Virginia Postrel’s reaction in Bloomberg by explaining that there is a bit more to elite Ivy League nicey-goodiness than may be recognized by outsiders not fully acquainted with the culture and patterns of expression of this particular tribe.

[There is an] element of ruthlessness that runs through the culture of elite colleges, and… the prevailing spirit of deference and niceness is a defense mechanism and a facade — a kind of ritualized politesse, like the elaborate bowing and flowery compliments of a 17th century European court, that conceals the vaulting ambitions and furious rivalries that actually predominate on campus. (The essential ruthlessness of the meritocracy was one of the themes of my own subsequent attempt to distill the culture of elite education.) Which is why I appreciated how Postrel’s column finishes up.

Harvard is the strongest brand in American higher education, and its identity is clear. As its students recognize, Harvard represents success. But, it seems, Harvard feels guilty about that identity and wishes it could instead (or also) represent “compassion.†These two qualities have a lot in common. They both depend on other people, either to validate success or serve as objects of compassion. And neither is intellectual.

Rochefoucauld observed that hypocrisy was the tribute that vice pays to virtue.

I suppose it would be fair to say that constant poses of kindness and compassion are the tribute, these days, that the excessively ambitious and success-obsessed pay to failure.

“My board scores and grades were infinitely better than yours. I’m going to Harvard and on to a prominent bank or law firm and seven figures annually. But I will support plenty of welfare entitlement programs for you losers down in the bad neighborhood.”

Hat tip to Frank A. Dobbs.

13 May 2011

Walter Russell Mead, writing in the American Interest, though a classic representative of the liberal elite, is increasingly uneasy about his own class’s characterstic contempt for their fellow citizens, attitudes of self-entitlement, anti-patriotism, and aversion of self-doubt.

To listen to many bien pensant American intellectuals and above-the-salt journalists, America faces a shocking problem today: the cluelessness, greed, arrogance and bigotry of the American public. American elites are genuinely and sincerely convinced that the American masses don’t understand the world, don’t realize that American exceptionalism is a mental disease, want infinite government benefits while paying zero tax, and cling to their Bibles and their guns despite all the peer reviewed social science literature that demonstrates the danger and the worthlessness of both. …

But by historical standards, the average American is actually ahead of his or her ancestors. Today’s average Americans are smarter, more sophisticated, better educated, less racist and more tolerant than ever before. Immigrants face less prejudice in the United States than ever before in our history. Religious, ethnic and sexual minorities are more free to live their own lives more openly with less fear than ever before. There is more respect for science and learning, more openness to the arts and more interest in the viewpoints of other countries and cultures among Americans at large than in any past generation.

The American people aren’t perfect yet and never will be — but by the standards that matter to the Establishment, this is the best prepared, most open minded and most socially liberal generation in history. …

By contrast, we have never had an Establishment that was so ill-equipped to lead. It is the Establishment, not the people, that is falling down on the job.

Here in the early years of the twenty-first century, the American elite is a walking disaster and is in every way less capable than its predecessors. It is less in touch with American history and culture, less personally honest, less productive, less forward looking, less effective at and less committed to child rearing, less freedom loving, less sacrificially patriotic and less entrepreneurial than predecessor generations. Its sense of entitlement and snobbery is greater than at any time since the American Revolution; its addiction to privilege is greater than during the Gilded Age and its ability to raise its young to be productive and courageous leaders of society has largely collapsed. …

Many problems troubling America today are rooted in the poor performance of our elite educational institutions, the moral and social collapse of our ‘best’ families and the culture of narcissism and entitlement that has transformed the American elite into a flabby minded, strategically inept and morally confused parody of itself. Probably the best depiction of our elite in popular culture is the petulantly narcissistic Prince Charming in Shrek 2; our educational institutions are like the Fairy Godmother, weaving shoddy, cheap, feel-good illusions into a gossamer tissue of flattering lies. …

Some of the problem is intellectual. For almost a century now, American intellectual culture has been dominated by the values and legacy of the progressive movement. Science and technology would guide impartial experts and civil servants to create a better and better society. For most of the American elite today, progress means ‘progressive’; the way to make the world better is through more nanny state government programs administered by more, and more highly qualified, lifetime civil servants. Anybody who doubts this is a reactionary and an ignoramus. This isn’t just a rational conviction with much of our elite; it is a bone deep instinct. Unfortunately, the progressive tradition no longer has the answers we need, but our leadership class by and large cannot think in any other terms.

The old ideas don’t work anymore, but the elite hates the thought of change.

Past generations of the American elite were always a little bit nervous about their situation; it is morally difficult for an elite based on birth, ethnicity or wealth to justify itself in a country with the universalist, democratic values of the United States. The tendency of American life is always to erode the power and prestige of elites; populism is the direction in which America likes to travel. Past generations of elites were conflicted about their status and struggled against a sense that it was somehow un-American to set yourself up as better than other people.

The increasingly meritocratic elite of today has no such qualms. The average Harvard Business School and Yale Law School graduate today feels that privilege has been earned. Didn’t he or she score higher on the LSATs than anyone else? Didn’t he or she previously pass the rigorous scrutiny of the undergraduate admissions process in a free and fair process to get into a top college? Haven’t they been certified as the best of the best by impartial experts?

A guilty elite may be healthier for society than a self-righteous one.

Read the whole thing.

29 Mar 2011

Richard Kahlenberg, in the Chronicle of Higher Education, reviews a book by Toronto sociologist Ann L. Mullen, looking at the differences in student demographics, life style, academic major, and expectations between Yale and Southern Connecticut State University, a nearby former Normal School (i.e., a teacher’s training school) upgraded in recent years to university status.

Mullen examines two four-year colleges located within two miles of one another: Yale University and Southern Connecticut State University. In racial terms, the two institutions are not all that different. Yale is 69 percent white, while Southern is 70 percent white. But as Mullen finds in interviews with 50 Yale students and 50 Southern students, the class divide is significant, and that difference has enormous implications for the attitudes, experiences, and expectations of students.

Mullen’s insightful new book, Degrees of Inequality , notes that Southern students tend to be the sons and daughters of “shopkeepers, secretaries, teachers, and construction workers,†about half of whom never completed college. By contrast, about 80 percent of Yale students sampled had parents with BA’s, two-thirds had some form of graduate education, and more than half came from the top 15 percent by income nationally. These students often “arrived on the back of tremendous childhood advantages.†, notes that Southern students tend to be the sons and daughters of “shopkeepers, secretaries, teachers, and construction workers,†about half of whom never completed college. By contrast, about 80 percent of Yale students sampled had parents with BA’s, two-thirds had some form of graduate education, and more than half came from the top 15 percent by income nationally. These students often “arrived on the back of tremendous childhood advantages.â€

Among the advantages, she writes, were high parental expectations. In interviews, she writes, it was clear that most Yale students “never actually decided to go to college; it was simply the next step in their lives, one not requiring a rationale.†Although less than one percent of four- year college students attend Ivy League institutions, for some Yale students interviewed, “it was a question of which one.†She writes, “It is not simply that they aspired to attend the most elite institutions; rather, they planned on it.

Southern students, by contrast, made a conscious decision to pursue higher education and then mostly chose Southern based on “cost and convenience.†Neither factor was mentioned by a single Yale student. Over 90 percent of Yale students were from out of state, while over 90 percent of Southern students came from in-state. The Southern students never thought of applying to Yale, and the Yale students have never even heard of Southern.

The differences in opportunities and outlooks of Yale and Southern are then amplified once they reach college, Mullen finds. Yale, founded 300 years ago, has a $15-billion endowment “about two thousand times greater†than the endowment of Southern, which became a four-year institution in 1937 and became part of the Connecticut State University system in 1983.

The economic chasm between the schools and their students also drives profound differences in the experiences at each institution. To save money, only about one-third of Southern students live on campus and only 24 percent participate in extracurriculars, as many have to work 20-30 hours a week. By contrast, almost all students at Yale live on campus, and 67 percent participate in extracurriculars, from playing tennis to singing a capella.

Asked what they value most about college, Yale students tended to mention learning from friends and peers and participating in extracurricular activities. Southern students were only half as likely as Yale students to mention peers and friends.

Academic pursuits also differ greatly. Deciding on a college major is usually portrayed as a matter of individual choice, Mullen notes, but economic constraints are strongly felt. “For the Southern students,†she says, “majors represented not bodies of knowledge or academic disciplines, but rather occupational fields.†By contrast, Yale students were “quite cognizant†that their Ivy League degrees made the field of study chosen less important. One student told Mullen, “I’m getting a diploma with four letters Y-A-L-E on it. I should be able to have the sky be my limit.â€

Surprise, surprise! Professor Mullen discovers the third-oldest and one of the most competitive colleges in the country attracts a more affluent and more cosmopolitan student body with larger ambitions and wider career options than those of students attending the local neighborhood’s uncompetitive teacher’s college.

Certainly a lot of Yale students come from more affluent and better educated family backgrounds, but comparing Yale and Southern most meaningfully would have to be done on the basis of academic talent. Southern’s students have average SAT scores in the 480-490 range on the three parts of the current test. Yale quotes different 25%/75% figures, which indicate that only 25% of Yale students got under 700 on any of the three parts of the SAT, and another 25% got 780 to 800. Yale admits around 7.5% of applicants these days. Southern admits 71% of applicants.

Yale students have different majors and different career options from students at Southern Conn, not because Yalies have inherited clout, but because they are, on the average, a great deal more academically competent and competitive.

In my day, Southern and Yale did interact a bit socially, most commonly via contact within the Connecticut Intercollegiate Student Legislature (CISL). Yalies dated girls from Southern, and I knew some people who married them.

Hat tip to David H. Nix.

31 Jan 2011

Tom Smith is worried that all that overachieving may lead to a sense of entitlement encompassing rather more than a lot of Americans might like.

[I]f some parents want to push their children, even to an extent that seems crazy to me, so that they will end up wonderful musicians or inventive scientists, this is much to my advantage. Who knows, little tiger girl may end up playing Mahler in a new way, and add some new meaning to my life. I may download that mp3, listen to it on my iPod or whatever we have 25 years from now, and the world will be a little better place. Or some Tiger dad will make his kitten memorize the periodical table at age three and when he grows up he will invent donuts that make one lose weight. You never know. It could happen. These would be good things for the world, maybe not so much for the kid, or maybe it would. I am happy leaving that one for the psychologists.

But here’s the thing. And here the point has been made easier to make by the curious fact that Tiger Mom is a Yale Law School professor and as Professor Bainbridge has pointed out, it seems almost an epidemic among faculty parents in New Haven. My fear is that little tiger kittens are not being groomed to make things that you and I can buy if we feel like it. I’m afraid, call me paranoid if you like, that those little achievers will want to grow up to, well, rule. Not in the imperial Chinese way, though I take it that is the ultimate inspiration for this model of child rearing. If my high school understanding of Chinese history is correct, that Empire used to be ruled by a giant bureaucracy into which one got by passing extraordinarily difficult exams, competing against other fanatically hopeful parents who saw it as one of the few ways to get the young persons out of a life of horrible drudgery. But rather in something more like the imperial Chinese way than my ideal, which is more like Thomas Jefferson’s, without the antique and misguided dislike of commerce. So, if I’m sitting in the middle of my Jeffersonian space, able to order whatever I want, within my budget of course, from Amazon, working at something I like, not taxed to death or harassed by officious officials; if I can provide for my family and hope to provide a similarly independent life for my offspring, then what’s it to me if some mom somewhere wants to drive her children so that someday they will produce a recording or a pill I might want to buy? Only good. But if we are sliding toward a world like the one that is, to exaggerate only a little, like that I was taught we should be sliding toward when I restlessly roamed the hallowed halls the The Yale Law School many years ago, then I am not so sanguine. Then I worry that all this fierce intelligence, all this ambition, all this work are going toward the building of world in which my children will be mere, well, what do you call the people who support those who so intelligently manage things from on top. Not to mention the unbelievably well educated 35 year old who will tell me someday I didn’t score well enough in some algorithm I can’t even understand to get my arteries bypassed or my prostate cancer treated. I want to live in a world, and I want my children to as well, where we are free individuals, and geniuses can sell us stuff if we want to buy it. When I suspect the little elites of tomorrow are just being made more formidable still, it excites not my admiration as much as my anxiety.

Hat tip to Glenn Reynolds.

16 May 2010

Peggy Noonan reflects on the ironies of American meritocracy laboring mightily… and delivering an establishment full of socialists. And exactly how committed to socialism is the successful gamesman who has finally clambered all the way to the top by hard work, talent, and no small quantity of discretion and craft?

Personally, I tend to suspect that Socialism functions in much the same way for these people that Religion used to for earlier establishmentarians. One regularly attends services and is officially a member of the church, but it has not got a lot to do with one’s actual business life.

What is interesting about the nomination is that all the criticisms serious people have lobbed about so far are true. Yes, she is an ace Ivy League networker. Yes, career seems to have been all, which speaks of certain limits, at least of experience. She has been embraced by the media elite and all others who know they will be berated within 30 seconds by an irate passenger if they talk on a cellphone in the quiet car of the Washington-bound Acela. (If our media elite do not always seem upstanding, it is in part because every few weeks they can be seen bent over and whispering furtively into a train seat.) Ms. Kagan and her counterparts all started out 30 years ago trying to undo the establishment, and now they are the establishment. If you need any proof of this it is that in their essays and monographs they no longer mention “the establishment.”

Ms. Kagan’s nomination has also highlighted America’s ambivalence about what we have always said we wanted, a meritocracy. Work hard, be smart, rise. The result is an aristocracy of wired brainiacs, of highly focused, well-credentialed careerists. There’s something limited, even creepy, in all this ferocious drive, this well-applied brilliance. There’s a sense that everything is abstract to those who succeed in this world, that what they know of life is not grounded in hard experience but absorbed through screens—computer screens, movie screens, TV screens. Our focus on mere brains is creepy, too. Brains aren’t everything, heart and soul are something too. We do away with all the deadwood, but even dead trees have a place in the forest.

The ones on top now and in the future will be those who start off with the advantage not of great wealth but of the great class marker of the age: two parents who are together and who drive their children toward academic excellence. It isn’t “Mom and Dad had millions” anymore as much as “Mom and Dad made me do my homework, gave me emotional guidance, made sure I got to trombone lessons, and drove me to soccer.”

We know little of the inner workings of Ms. Kagan’s mind, her views and opinions, beliefs and stands. The blank-slate problem is the post-Robert Bork problem. The Senate Judiciary Committee in 1987 took everything Judge Bork had ever said or written, ripped it from context, wove it into a rope, and flung it across his shoulders like a hangman’s noose. Ambitious young lawyers watched and rethought their old assumption that it would help them in their rise to be interesting and quotable. In fact, they’d have to be bland and indecipherable. Court nominees are mysteries now.

Which raises a question: After 30 years of grimly enforced discretion, are you a mystery to yourself? If you spend a lifetime being a leftist or rightist thinker but censoring yourself and acting out, day by day, a bland and judicious pondering of all sides, will you, when you get your heart’s desire and reach the high court, rip off your suit like Superman in the phone booth and fully reveal who you are? Or, having played the part of the bland, vague centrist for so long, will you find that you have actually become a bland, vague centrist? One always wonders this with nominees now.

23 Feb 2010

Ten rules (sometimes fewer) for writing fiction from Elmore Leonard, Dianna Athill, Margaret Atwood, Roddy Doyle, Helen Dunmore, Geoff Dyer, Anne Enright, Richard Ford, Jonathan Franzen, Esther Freud, Neil Gaiman, David Hare, P.D. James, AL Kennedy, Hilary Mantel, Michael Moorcock, Michael Morpurgo, Andrew Motion, Joyce Carol Oates, Annie Proulx, Philip Pullman, Ian Rankin, Will Self, Helen Simpson, Zadie Smith, Colm TóibÃn, Rose Tremain, Sarah Waters, Jeanette Winterson.

—————————————————-

Col. George Washington, Foxhunter (Ralph Boyer, aquatint, Fathers of American Sport, Derrydale Press, 1931)

One day belated notice of the birthday of our neighbor and compatriot in the hunting fields of Clarke County, George Washington.

When he was 14 or 15 years old, George Washington copied out by hand 110 “Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation.”

Washington’s maxims came from a translation of a treatise Bienseance de la Conversation entre les Hommes produced by the pensonnaires of the Jesuit Collège Royal Henry-Le-Grand at La Flèche in 1595. René Descartes studied at the same college just a few years later, 1607 to 1615.

The case of George Washington, I would suggest, can be taken to demonstrate that residence at Harvard, Yale, or even La Flèche is not an absolute requirement for leadership success or good manners.

—————————————————-

WSJ comments on the Obama plan to ram the health care bill through, damn the rules of the Senate and the wishes of the public.

The larger political message of this new proposal is that Mr. Obama and Democrats have no intention of compromising on an incremental reform, or of listening to Republican, or any other, ideas on health care. They want what they want, and they’re going to play by Chicago Rules and try to dragoon it into law on a narrow partisan vote via Congressional rules that have never been used for such a major change in national policy. If you want to know why Democratic Washington is “ungovernable,” this is it.

—————————————————-

David Brooks discovered that something has gone wrong with the meritocratic revolution, and wonders if this might have something to do with the new elite not being quite so meritorious as had been supposed.

[H]ere’s the funny thing. As we’ve made our institutions more meritocratic, their public standing has plummeted. We’ve increased the diversity and talent level of people at the top of society, yet trust in elites has never been lower.

It’s not even clear that society is better led. Fifty years ago, the financial world was dominated by well-connected blue bloods who drank at lunch and played golf in the afternoons. Now financial firms recruit from the cream of the Ivy League. In 2007, 47 percent of Harvard grads went into finance or consulting. Yet would we say that banks are performing more ably than they were a half-century ago?

Government used to be staffed by party hacks. Today, it is staffed by people from public policy schools. But does government work better than it did before?

Journalism used to be the preserve of working-class stiffs who filed stories and hit the bars. Now it is the preserve of cultured analysts who file stories and hit the water bottles. Is the media overall more reputable now than it was then?

The promise of the meritocracy has not been fulfilled. The talent level is higher, but the reputation is lower.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Meritocracy' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|