Category Archive 'Regulation'

30 May 2017

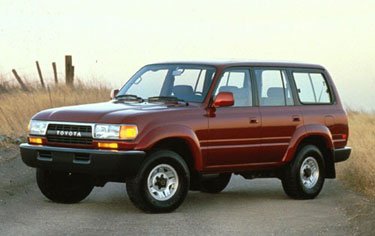

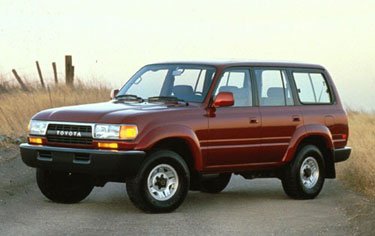

My solution: a 1992 Toyota Land Cruiser. I’ve mounted a 1930s Alvis Hare mascot on the hood.

Eric Peters warns that buying your next car new could be a terrible mistake.

t’s a great time to buy a used car as far as the deal you’ll get.

It’s a smart move, because of the hassle you’ll avoid.

Maybe not right away but down the road — probably just after the warranty coverage expires.

What’s happened is we’ve crossed a kind of engineering Rubicon. It has happened over the past two or three years — and there is probably no turning back, not unless regulatory reasonableness returns — and that doesn’t look likely. If anything, it is likely to become less and less reasonable.

The car companies have had to resort to design and engineering measures just as desperate and extreme as the financial measures to which they are resorting to fluff up sales. But in the case of the design and engineering measures, it is to placate federal regulatory ayatollahs, who continue to demand, among other things, that new vehicles achieve ever-higher fuel economy — and lower “greenhouse emissions†— irrespective of the cost involved.

It is why, next year, BMW will append a four-cylinder/hybrid drivetrain to all 5 Series sedans — and eliminate the six-cylinder/non-hybrid versions.

It is why every new-design car has a direct injected (DXI or GDI) engine rather than a port fuel injected engine. Automatic Stop/Start systems are pretty much standard equipment, which you can’t cross off the options list.

The latest automatic transmissions have eight — or even ten — speeds. Turbochargers, sometimes two of them, are the new In Thing.

Bodies are being made from aluminum rather than steel.

And, of course, there is “autonomous†driving technology — cars that semi-steer and park themselves, accelerate and brake on their own.

None of these things materially improves the performance — or even the economy — of the vehicle in a way that’s meaningful to the owner.

A car with DI and an eight-speed transmission might give you a 3-4 MPG uptick on paper vs. the same basic vehicle without these technologies.

That’s not nothing, of course.

But it doesn’t cost nothing, either.

Not much is said about the fact that the car costs more to buy because it has these technologies. You “save on gas†— by spending more on the car. The same logic used to peddle hybrids.

It’s interesting that this other side of the equation is almost never discussed and that the ayatollahs who smite us with their regulatory fatwas — so seemingly concerned about how much we’re spending on gas — never seem much concerned about how much we’re spending to cover the cost of their fatwas.

Up front — and down the road.

These turbocharged, direct-injected, stop-starting cars — with their eight and nine and ten speed transmissions and aluminum bodies — deliver the goods (MPGs) when new. Enough so that the car companies achieve “compliance†with whatever the latest federal fatwas are, at any rate.

But what happens as they get old?

I’ve written before about what’s already happening. About relatively young cars — less than ten years old, sometimes — becoming economically unfixable (that is, not worth fixing) when, for instance, the uber-elaborate transmission fails.

You have an otherwise sound car: an engine that will probably run reliably for another 100,000 miles, an un-rusty body and paint that still looks great. The overall car’s not a junker — but the transmission is junk. So you have it towed to the shop, expecting to get the tranny (not Caitlyn) rebuilt. And the guy tells you they don’t do that anymore. Rebuild — or repair.

They replace.

You must buy a new (or “remanufacturedâ€) transmission, because they’ve become too complicated and time-consuming to deal with on a work bench. You are faced with spending $5,000 on a replacement transmission for a car that’s worth $8,000.

Gotcha.

Older cars made with economically sane five and six-speed transmissions remain economically repairable. But they do not make them new anymore. Not many, anyhow.

And not for much longer.

It is not just that, either.

Last week, I reviewed the last of the Mohicans — as far as full-size trucks. The 2017 Toyota Tundra. It is the only current-year, full-size truck you can still buy that does not have a direct-injected engine. This means it will never have a carbon-fouling problem — as Ford and others who have added DI to their engines, to squeeze out an MPG or three more, to please Uncle, have regularly been having.

Actually, it’s you — if you own one of these DI’d rigs — who will have the problem.

And be paying to un-crud your direct-injected engine, which may involve partial disassembly of the engine. This is not like changing the oil. Nor will it cost you $19.99, either.

Ford’s solution to the DI blues? It will be adding a separate port fuel injection circuit to its direct-injected engines next year. So, the vehicles will have two fuel injection systems. You’ve just double your odds of having a fuel system problem at some point.

The point here is it’s not just one thing; it is a synergistic multiplicity of things that are bringing into actuality the Planned Obsolescence people used to grumble about — but which was mostly not the case. Until just the past several years, most cars were usually economically repairable well into their senior years. It made sense to put, say, $2,000 for a rebuilt (four or five-speed) automatic into a car worth $8,000.

But with all the complex, fragile, non-serviceable, and hugely expensive-to-replace-when-it-fails stuff they are grafting onto cars to make them Uncle friendly, they become not worth fixing long before the cars themselves have reached their liver-spotted years.

The truth is that probably every car made since about 2015 is a Latter Day Throw-Away. It will run beautifully for about ten years. Just a bit longer than those $500/month payments we were making.

RTWT

I reached the same conclusion after buying my last BMW. It came with no dipstick. (You get to rely on the computer, which is useless and wrong anytime your battery is low, the temperature is too cold, the wiring gets wet, &c., &c.) It also came with no spare tire. Instead, we got run-flat tires which set off flat-tire warnings all the time on dirt roads, which had terrible traction on wet roads, and which were good for 10K miles. I’m used to getting 50K miles on normal Michelins.

There is, each year, more and more expensive crap built into automobiles, and fewer and fewer choices left to the unlucky car owner. I never wanted seat belts to begin with, let alone air bags.

Personally, I intend to go even farther back into automotive history than the author advises. My next car is going to have no computer at all, but will have a distributor and carburetors, and be much easier to work on.

02 May 2017

John Singleton Copley, A Boy with a Flying Squirrel. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Atlas Obscura informs us that a once common custom was obliterated by a change in fashion which then became cemented into Progressive Era regulation.

In 1722, a pet squirrel named Mungo passed away. It was a tragedy: Mungo escaped its confines and met its fate at the teeth of a dog. Benjamin Franklin, friend of the owner, immortalized the squirrel with a tribute.

“Few squirrels were better accomplished, for he had a good education, had traveled far, and seen much of the world.” Franklin wrote, adding, “Thou art fallen by the fangs of wanton, cruel Ranger!”

Mourning a squirrel’s death wasn’t as uncommon as you might think when Franklin wrote Mungo’s eulogy; in the 18th- and 19th centuries, squirrels were fixtures in American homes, especially for children. While colonial Americans kept many types of wild animals as pets, squirrels “were the most popular,” according to Katherine Grier’s Pets in America, being relatively easy to keep. …

While many people captured their pet squirrels from the wild in the 1800s, squirrels were also sold in pet shops, a then-burgeoning industry that today constitutes a $70 billion business. One home manual from 1883, for example, explained that any squirrel could be bought from your local bird breeder. But not unlike some shops today, these pet stores could have dark side; Grier writes that shop owners “faced the possibility that they sold animals to customers who would neglect or abuse them, or that their trade in a particular species could endanger its future in the wild.”

Keeping pet squirrels has a downside for humans too, which eventually became clear: despite their owners’ best attempts at taming them, they’re still wild animals. As time wore on, squirrels were increasingly viewed as pests; by the 1910s squirrels became so despised in California that the state issued a widespread public attack on the once-adored creatures. From the 1920s through the 1970s many states slowly adopted wildlife conservation and exotic pet laws, which prohibited keeping squirrels at home.

RTWT

12 Apr 2017

United Airlines CEO Oscar Munoz.

Kevin D. Williamson explains that the big ugly corporations that we particularly hate, by some curious coincidence, really tend to be exactly the ones which are most in bed with the regulatory state.

Capitalism is unpopular for four reasons: banks, health-insurance companies, cable providers, and airlines. These all have something in common.

Airlines are in the wringer this week, with United shaming itself in spectacular fashion: Having overbooked a flight and seated the passengers, the company found itself needing four seats—not for paying customers but for airline employees who needed to be moved to another airport. When they did not find any takers for their paltry travel-voucher offers, they simply dispatched armed men to the airplane to force paying customers off, in a now-famous case, literally dragging one of them away. …

The FAA Consortium in Aviation Operations Research estimated a few years back that the inability of U.S. airlines to deliver the services they have been paid for and that they agreed to deliver costs businesses something like $17 billion. But that does not really capture the expense. A conference I attended not long ago was scheduled to get under way in the afternoon, but all of those who were speaking or who had other formal roles at the event were contractually required to arrive the evening before. There was plenty of time to fly in on the morning of the conference and arrive well before the opening of the conference, assuming the airlines kept to their schedule — but the organizers, who are not fools, were not willing to bet on that happening. I did a little back-of-the-envelope English-major math and concluded that the extra hotel rooms alone must have added a six-figure sum to the organizers’ expenses; if a significant number of the guests followed suit and decided not to bet on the airlines’ keeping their schedules, then the extra expenditure would have easily exceeded $1 million. There are thousands of events like that around the country every day. …

The airlines are terrible, of course, and every time one of them goes kaput, I do a little happy dance . . . until I remember that all that means is that the equally terrible remaining airlines have less competition. …

Airlines are like banks, health-insurance companies, and cable providers in that they work in very heavily regulated industries with relatively low profit margins, which creates enormous pressure for consolidation. (Notice how many health-insurance companies ditched markets they had previously served after the grievously misnamed Affordable Care Act was passed.) Those industries also are alike in that the relatively few players who remain in the market are heavily constrained by public-sector actors with powers that no private-sector monopoly would ever dare to dream of: the Federal Reserve, Medicare, the FCC, and the motley gangs of bureaucrats that have a hand in the airline business.

n the United States, it is regulation, not deregulation, that prevents foreign carriers from competing in the domestic market, which is not the case in New Zealand, which entered into a number of open-skies agreements to increase domestic competition, something our dinosaur airlines have fought against tooth and talon. And in New Zealand, airlines are obliged to compensate passengers if they bump them—up to ten times the cost of the ticket. No so in the United States.

And that points to one of the biggest reasons people hate banks, cable companies, health-insurance companies, and airlines: There is an in-your-face asymmetry of power. If the airline says your flight is going to be delayed by two hours — not because of a hurricane or unforeseeable events but because of straightforward managerial incompetence — then you basically have to live with it. You don’t get to say: “Okay, but I’m taking $50 off the airfare.†Your bank expects you to accept screw-ups on its part that might cost you hundreds or thousands of dollars if the mistake was yours. (My bank just spent 46 cents to send me a check for . . . 47 cents . . . because apparently I bank with people who cannot quite manage to calculate interest correctly.) Your cable service may go out for hours at a time, but if you’re one minute late with your payment, expect penalties.

That is one major problem with heavily regulated industries in which there is insufficient competition: The managers act as though the business were organized for their benefit rather than for the customers, and that attitude seeps down to front-line workers. The typical airline employee treats the typical traveler as though he simply is in the way. I once was introduced to an executive who informed me that he was in charge of “strategic planning†for a large municipal utility company. I asked him whether his strategic plan was to keep being a monopoly. “I’d really be exploring that angle, strategic-planning-wise,†I advised. He did not seem to appreciate my counsel.

If I were a better sort of person, I’d have a little sympathy for the senior executives at United, who must be having a hell of a week. I am not a better sort of person, and I’d be content to see them flogged in the streets. But that’s no way to make policy.

30 Dec 2016

Inside the Beltway there are loads of enormous buildings, each with its own campus, and each filled with thousands and thousands of people dedicated to stopping your toilet from flushing right, making your appliances cease to function properly, messing with your engine’s performance, taking the spare tire out of your car, and making everything more expensive.

Jeffrey Tucker visited Brazil and enjoyed taking an old-fashioned shower.

We have long lived with regulated showers, plugged up with a stopper imposed by government controls imposed in 1992. There was no public announcement. It just happened gradually. After a few years, you couldn’t buy a decent shower head. They called it a flow restrictor and said it would increase efficiency. By efficiency, the government means “doesn’t work as well as it used to.â€

We’ve been acculturated to lame showers, but that’s just the start of it. Anything in your home that involves water has been made pathetic, thanks to government controls.

You can see the evidence of the bureaucrat in your shower if you pull off the showerhead and look inside. It has all this complicated stuff inside, whereas it should just be an open hole, you know, so the water could get through. The flow stopper is mandated by the federal government.

To be sure, the regulations apply only on a per-showerhead basis, so if you are rich, you can install a super fancy stall with spray coming at you from all directions. Yes, the market invented this brilliant but expensive workaround. As for the rest of the population, we have to live with a pathetic trickle.

It’s a pretty astonishing fact, if you think about it. The government ruined our showers by truncating our personal rights to have a great shower even when we are willing to pay for one. Sure, you can hack your showerhead but each year this gets more difficult to do. Today it requires drills and hammers, whereas it used to just require a screwdriver.

The water pressure in our homes and apartments has been gradually getting worse for two decades. I had to laugh when Donald Trump made mention of this during the campaign. He was challenged to name an EPA regulation he didn’t like. And recall that he is in the hospitality business and knows a thing or two about this stuff.

“You have showers where I can’t wash my hair properly,†he said. “It’s a disaster. It’s true. They have restrictors put in. The problem is you stay under the shower for five times as long.”

The pundit class made fun of him, but he was exactly right! This is a huge quality of life issue that affects every American, every day.

It’s not just about the showerhead. The water pressure in our homes and apartments has been gradually getting worse for two decades, thanks to EPA mandates on state and local governments. This has meant that even with a good showerhead, the shower is not as good as it might be. It also means that less water is running through our pipes, causing lines to clog and homes to stink just slightly like the sewer. This problem is much more difficult to fix, especially because plumbers are forbidden by law from hacking your water pressure.

The combination of poor pressure and lukewarm temperatures profoundly affects how well your dishwasher and washing machine work.As for the heat of the water, the obsession over “safety†has led to regulations that the top temperature is preset on most water heaters, at 120 degrees Fahrenheit, which is only slightly hotter than the ideal temperature for growing yeast. Most are shipped at 110 degrees in order to stay safe with regulators. This is not going to get anything really clean; just the opposite. Water temperatures need to be 140 degrees to clean things. (Looking at the industry standard, 120 is the lowest-possible setting for cleaning but 170 degrees gives you the sure thing.)

The combination of poor pressure and lukewarm temperatures profoundly affects how well your dishwasher and washing machine work. Plus, these two machines have been severely regulated in how much energy they can consume and how much water they can use. Top-loading washing machines are a thing of the past, while dishwashers that grind up food and send it away are a relic. We are lucky now to pull out a glass without soap scum on it. As for clothing, what you are wearing is not clean by your grandmother’s standards.

So you might have a vague sense that your clothing and dishes aren’t coming out as clean as they might have in the past. This is exactly right. But because we don’t have a direct comparison, and these regulations have taken many years to gradually unfold and take over our lives, we don’t notice this as intensely.

When you travel to Brazil, Australia, New Zealand, or Switzerland – and probably many places I’ve never been – you are suddenly shocked. Why does everything work so well? Why don’t things work as well in the US? The answer is one word: government. This is the only reason.

Read the whole thing.

11 Jun 2016

From Matthew Johnson on Facebook:

(Apologies for the hard-to-read images. They won’t enlarge or sharpen better. Facebook images are small.)

02 Apr 2016

Robert Arvanitis explains that their utility and functions have changed.

This begins with the historical merchant banks. These were firms that helped fund the Age of Exploration, and grew along with their clients during the Industrial Revolution.

A merchant banker was knowledgeable in one or more lines of business, put his own money into investments, and gathered more investors based on his own reputation. A merchant banker was the finance department for his clients. He not only lent and invested, he advised on markets, delivered correspondent services, knew the broader economy, and participated in the risks.

That was a lot of hard work, and a lot of sincere risk taking, and the merchant bankers were well-respected. …

as government grew, it had a baleful impact on banking. Government imposed increasing regulation, it set ever more complex tax schemes, and it used capital markets for its own deficit financing. The classic “elephant in the bath tub†of economic distortions.

By the 1970s, the investment banks, starting with Drexel, responded to these new signals. Investment banks began to disintermediate the commercial banks, with high yield bonds. Here, the investment banks acted as agent, not principal. They matched borrowers to investors but took no principal risk. That removed the need for capital, but also left the investors with both the default and liquidity risk. This further detached banks from clients, and in fact made them competitors in trading.

It turned out there were more — and more profitable — opportunities in arbitraging tax and regulation than there were in actually serving businesses. …

[T]he new-style investment bankers sold bonds to investors, and then traded against both the investors and the issuers, making a relatively safe turn on each sale. Or else they read the tax code, and fabricated deals that were tax-deductible debt for the IRS, but counted as regulatory capital for the other parts of government. That’s easier and more profitable than actually building something.

In short, rather than solving real challenges, today’s investment banks work to exploit the growing incoherent web of government intrusions on the market. Profitable, yes, but not worthy of our respect.

05 Jun 2015

Cato Institute:

Analyst Dale Gieringer figured that the benefits of FDA regulation “could reasonably be put at some 5,000 casualties per decade or 10,000 per decade for worst-case scenarios. In comparison … the cost of FDA delay can be estimated at anywhere from 21,000 to 120,000 lives per decade.â€

Hat tips to Sarah Jenislawski and Jim Harberson.

05 May 2015

1992 Toyota Land Cruiser. The paint on ours is a little rougher, and I’ve mounted a 1920s Alvis Hare hood ornament on it.

Sam Smith, in Wired, explains why many enthusiasts are collecting old pieces of crap, instead of buying new cars.

[A]s far as I can tell, this affliction is rooted in what we’ve lost. Call it simplicity or purity, maybe even character, born not of wear or time, but of freedom of design. And an obsession with the fundamental quirks that give a car personality. Things like floor-hinged pedals, gated shifters, or doors whose latches feel deeply mechanical, like the cocking of a gun. And if you drive a lot of new cars, you realize that stuff is growing rarer by the minute.

It is a byproduct of progress. On paper, a new BMW M3 is superior to any before it. The modern car accelerates harder, stops quicker, and is quieter and more comfortable than an M3 built in the 1990s. Any engineer will point to it as a less compromised product. But compromise is character. The older car is simpler and smaller. It was built to less aggressive crash standards, so it has thinner pillars and weighs less. You can see out of it easily, and the lack of weight helps the car give you feedback, so it’s more fun to drive at legal speed. The new one feels like a city bus by comparison.

Modern can be better, but it isn’t necessarily.

This isn’t a unique opinion, and these aren’t new arguments. Twenty years ago, people were looking to the vehicles of decades prior and bemoaning the increase in weight and complexity. In the late 1800s, the first automobiles were viewed as atrocities, far less civilized and romantic than horses. Rose-tinting the past while moving forward is human nature.

But looking back still has value. Many analysts, for example, now believe that the recent boom in classic-car values is due to the arc of new-vehicle development. Take the current Porsche 911 GT3: a fantastic car, but complex by the standards of even ten years ago. The electrically assisted power steering is distant. The car’s newly elongated wheelbase improves stability and ride, but at the expense of a cozy cabin and compact footprint. It’s also available only with an automatic transmission—a piece of equipment that takes an engaging job out of the driver’s hands.

Previous GT3s were deeply involving to drive and only available with manuals. When the new car was announced, older examples—even relatively recent models—saw a noticeable increase in value.

What have we gained? Everyone knows that restrictive legislation killed the grossly unsafe or heavily polluting car. That is inarguably good. As is the glut of durable, crashable and recyclable vehicles filling showrooms. We are living in something of a golden age of automobiles—more performance and relative fuel economy than ever before. And while new cars still break, statistically, they’re more reliable and efficient than at any point in history. The inevitable march toward perfection has given us direct-injected, turbocharged engines with fantastic performance and wonderful fuel economy, dual-clutch transmissions that deliver shifts in the blink of an eye, and electric cars virtually free of excuses.

Part of this is simply time. Computer-controlled engines have been common for over 30 years. Crash safety has been a science for longer than NASA’s Apollo program existed. Even the simple rubber tire is over a century old. Those are just three pieces of a complex machine, but cumulatively speaking, each has received more development hours than the Manhattan Project. Given similar time and engineering attention, anything would evolve to be good.

But if humanity is an assemblage of flaws, we’re slowly engineering the human out of the automobile. And the more new cars I drive, the more I find myself drawn to the “bad†old ones.

We bought the faster, most loaded 3-series BMW a few years back. The bloody thing actually came without a spare tire. BMW was cooperating with Big Brother and saving energy. The driver, you see, was supposed to not need a spare anyway, because BMW thoughtfully provided original equipment run-flat tires.

Those tires, mind you, were noisy and had an extremely bad grip on wet roads and dirt roads, and wore out after 10,000 miles, and cost a fortune to replace (I bought non-run-flat replacements), but you’re supposed to be happy that you’re saving the planet.

The car is fast as hell, but it has a lousy first gear. You really have to crank the revs up, or you will stall out. BMW included a new sort of turn signal switch as well. Move it left or right, and you don’t get a positive setting. You get a mushy sort of feel, and it blinks a few times and then goes back to off. You have to move it again to get it completely on. This, too, is supposed to be an improvement.

The radio, of course, was designed by some 13-year-old Oriental. You poke your finger at various illuminated bits, all of which do multiple things potentially.

What really torched me off was going out to check the oil, and finding that this car was built without a dipstick. The owner is intended to rely on his computer, the same computer (which if the battery ever get a little low) warns him emphatically that the car is dying and will momentarily blow up, the same computer which issues constantly all sorts of emoji symbols telling you that a bulb is out somewhere or your tire pressure is under 25 lbs.

My reaction was to swear a great oath that I’ll never buy a new BMW again. But, really, I don’t like being told what to do, and I’m coming to the conclusion that I may never buy a new car, period, again.

In the good old days, before we were born, a chap could go to Morris Garages in Oxford, England, and tell the nice men what sort of car he wanted: what kind of engine, supercharged or not, what kind of body style, what color, and he could specify all the little conveniences and accessories he desired. “I’ll have Brooklands windscreens, please!”

Today, federal cabinet departments conspire with enormous car manufacturing corporations to make all our decisions for us, for our own good.

Who would voluntarily pay several thousand dollars to put explosive airbags all over his car, knowing that there is an inevitable hazard that one of them might go off and knowing that one of those infernal devices might injure you or kill a kid? Possibly some mental defective living in California, but not you or me. But we have no choice. Some bureaucratic committee in Washington decided for us, and we get to pay. Next, we will be getting a grand or so worth of rear video camera and backing-up-to-park assistance.

And, that’s why a decent new car today costs $40,000-$50,000. My father used to go out, circa 1960, and get a shiny new car for $2000.

Karen had an unfortunate encounter with an oak tree atop the Blue Ridge, trying to come home in a howling blizzard a few years ago, and she totalled our SUV. I thought about it and bought an ancient (1992) Toyota Land Cruiser off of Ebay for $4000. That Land Cruiser was precisely what Sam Smith would describe as “a piece of crap.” Just about everything that could be wrong with a car was wrong with it, except for the body and the engine which were both just fine. Naturally, I had to drop a few more thousand into it immediately, but it runs, and it is spectacular at lumbering its way through mud and snow. I’m basically planning to keep it forever.

21 Sep 2014

Dan Greenfield explains how Progressivism has changed the fundamental nature of American society.

There are two types of societies, production societies and rationing societies. The production society is concerned with taking more territory, exploiting that territory to the best of its ability and then discovering new techniques for producing even more. The rationing society is concerned with consolidating control over all existing resources and rationing them out to the people.

The production society values innovation because it is the only means of sustaining its forward momentum. If the production society ceases to be innovative, it will collapse and default to a rationing society. The rationing society however is threatened by innovation because innovation threatens its control over production.

Socialist or capitalist monopolies lead to rationing societies where production is restrained and innovation is discouraged. The difference between the two is that a capitalist monopoly can be overcome. A socialist monopoly however is insurmountable because it carries with it the full weight of the authorities and the ideology that is inculcated into every man, woman and child in the country.

We have become a rationing society. Our industries and our people are literally starving in the midst of plenty. Farmers are kept from farming, factories are kept from producing and businessmen are kept from creating new companies and jobs. This is done in the name of a variety of moral arguments, ranging from caring for the less fortunate to saving the planet. But rhetoric is only the lubricant of power. The real goal of power is always power. Consolidating production allows for total control through the moral argument of rationing, whether through resource redistribution or cap and trade.

The politicians of a rationing society may blather on endlessly about increasing production, but it’s so much noise, whether it’s a Soviet Five Year Plan or an Obama State of the Union Address. When they talk about innovation and production, what they mean is the planned production and innovation that they have decided should happen on their schedule. And that never works.

You can ration production, but that’s just another word for poverty. You can’t ration innovation, which is why the aggressive attempts to put low mileage cars on the road have failed. As the Soviet Union discovered, you can have rationing or innovation, but you can’t have both at the same time. The total control exerted by a monolithic entity, whether governmental or commercial, does not mix well with innovation.

The rationing society is a poverty generator because not only does it discourage growth, its rationing mechanisms impoverish existing production with massive overhead. The process of rationing existing production requires a bureaucracy for planning, collecting and distributing that production that begins at a ratio of the production and then increases without regard to the limitations of that production.

Read the whole thing.

18 Jul 2014

Old-fashioned (now illegal) plastic gas can with built-in vent.

Jeffrey Tucker discusses in loving detail one prominent example of the countless ways in which government regulation has impacted the lives of just about every American.

[Y]esterday, [I ran out of gas and] had to get a can of gas from the local car shop. I started to pour it in. But, hmmm, this is strange. The nozzle doesn’t quite go in. I tilted it up and tried to jam it in.

I waited. Then I noticed gas pouring all down the side of the car. So I pulled it out and experimented by pouring it on the ground. There was some weird contraption on the outside and it wasn’t clear how it worked.

I poured more and more on the ground. Some got on my shoe. Some got on my hands. Some got on my suit.

Gas was everywhere really — everywhere but in the tank. It was a gassy mess. If someone had lit a match, I would have been a goner.

Finally I turned out the crazy nozzle thing a few times. It began to drip in a slightly coherent direction so I jammed it in. I ended up putting about one cup of gas in, started my car and made it to the gas station.

I’m pretty sure gas cans used to work. Yes. It was a can. It had a spout. It had a vent hole on the other side. You stuck in the spout and tipped. You never saw the gas.

Then government “fixed†the gas can. Why? Because of the environmental hazards that come with spilled gas. You read that right. In other words, the very opposite resulted. Now you cannot buy a decent can anywhere. You can look forever and not find a new one.

Instead you have to go to garage sales. But actually people hoard old cans. There is a burgeoning market in kits to fix the can.

The whole trend began in (wait for it) California. Regulations began in 2000, with the idea of preventing spillage. The notion spread and was picked up by the EPA, which is always looking for new and innovative ways to spread as much human misery as possible.

An ominous regulatory announcement from the EPA came in 2007: “Starting with containers manufactured in 2009… it is expected that the new cans will be built with a simple and inexpensive permeation barrier and new spouts that close automatically.â€

The government never said “no vents.†It abolished them de facto with new standards that every state had to adopt by 2009. So for the last five years, you have not been able to buy gas cans that work properly. They are not permitted to have a separate vent. The top has to close automatically. There are other silly things now, too, but the biggest problem is that they do not do well what cans are supposed to do. …

Never heard of this rule? You will know about it if you go to the local store. Most people buy one or two of these items in the course of a lifetime, so you might otherwise have not encountered this outrage.

Yet let enough time go by. A whole generation will come to expect these things to work badly. Then some wise young entrepreneur will have the bright idea, “Hey, let’s put a hole on the other side so this can work properly.†But he will never be able to bring it into production. The government won’t allow it because it is protecting us! ….

There is no possible rationale for these kinds of regulations. It can’t be about emissions really, since the new cans are more likely to result in spills. It’s as if some bureaucrat were sitting around thinking of ways to make life worse for everyone, and hit upon this new, cockamamie rule.

These days, government is always open to a misery-making suggestion. The notion that public policy would somehow make life better is a relic of days gone by. It’s as if government has decided to specialize in what it is best at and adopt a new principle: “Let’s leave social progress to the private sector; we in the government will concentrate on causing suffering and regress.†…

Ask yourself this: If they can wreck such a normal and traditional item like this, and do it largely under the radar screen, what else have they mandatorily malfunctioned? How many other things in our daily lives have been distorted, deformed and destroyed by government regulations?

If some product annoys you in surprising ways, there’s a good chance that it is not the invisible hand at work, but rather the regulatory grip that is squeezing the life out of civilization itself.

Read the whole thing.

Air conditioners which don’t cool as well as their predecessors made 60 years ago, toilets that won’t flush, automobiles without spare tires which cost more than the house you grew up in… the list of products of federal regulatory intervention to make the world a better place is long, and it keeps growing.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Regulation' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|