Category Archive 'Technology'

19 Jan 2020

Interior of the Pantheon in Rome.

In his excellent King Arthur’s Wars: The Anglo-Saxon Conquest of England (2016), retired British officer Jim Storr (now teaching at the Norwegian Military Academy in Oslo) puts the astonishing Roman technological achievements into perspective.

Roman engineers… were astonishingly skillful. In the years just before the birth of Christ they built an underground tunnel to bring water to Bologna in Italy. The tunnel was 20 kilometres long. Hundreds of years earlier they had drained the Pontine marshes south east of Rome. In the second century A.D. they brought water to a city in what is now Syria from a source over 130 kilometres away. It had an average gradient of just 3 centimetres’ fall in every kilometre. Many kilometers of it still exist today. In several cities in Europe, Roman aqueducts still provide water from several kilometres away. The world-famous Trevi fountain in Rome is supplied by the Virgo aqueduct, 22 kilometres long and built in 19 BC. The Pantheon in Rome was built in about 126 A.D. It is the world’s first large mass-concrete dome building. It is over 40 metres high and is visited by thousands of tourists, in complete safety, every day: almost 2000 years later.

Roman engineers were not just good builders. They were also world-class surveyors. If you walk south from London Bridge today, you soon reach Kennington Park Road (the A3). As you look along it you are looking in the precise direction of the east gate of Chichester, 59.84 Roman miles from the end of London Bridge. The surveyors who first laid out that road, probably in the first century A.D., knew precisely which direction Chichester lay in. There are two major rows of hills (the North and South Downs) in between.

In about 155 A.D. Roman surveyors re-aligned a section of 82 kilometres of frontier defenses in southern Germany. The southernmost 29 kilometres ran over several heavily wooded ridges, yet none of the forts (a Roman mile apart, with turrets in between) is off the direct line between start and finish by more than 1.9 metres. That is a deviation of less than five minutes of arc (five sixtieth of a degree). The accuracy which Roman surveyors achieved was phenomenal. It was only bettered with the invention of surveying instruments with magnifying optics (such as the theodolite) in the 17th century. Yet, as far as is known, Roman surveyors did not even have an instrument for observing and copying angles directly (such as a protractor). However, by about the year 500 or so, nobody could even build in stone, let alone lay out aqueducts or build in concrete. Concrete only came back into use in the late 18th century.

25 Sep 2019

New Apple Mac Pro and the 6K Pro Display XDR display.

Stephen Green approves of Apple’s new stratospherically-priced Pro computing equipment (even if he can’t afford that $999 stand).

At Apple’s annual World Wide Developer Conference (WWDC) earlier this week, the company announced its forthcoming modular Mac Pro, and its impressive accessory, the Pro Display XDR reference-class monitor. I watched the big keynote on Monday, and if the crowd winced when the Mac Pro’s starting price of $5,999 was revealed, you couldn’t tell. The auditorium full of developers maybe shifted in their seats a bit when they were told that the Pro Display would cost $4,999, but in the end they understood that a monitor with its specs is a game-changer for pros, because it goes toe-to-toe with the $40,000 (that’s right: forty-thousand dollars) displays Hollywood studios rely on.

But there were unhappy gasps when they heard that the XDR’s optional stand — and it is admittedly an impressive bit of engineering — would retail for $999. Sitting here at home, even I gasped a bit. The whole thing was just so much that it got Engadget’s Devindra Hardawar to opine that a “$999 monitor stand is everything wrong with Apple today.”

Au contraire, a $999 monitor stand is everything right with Apple today. And no, I’m not being facetious, or day-drinking any more than I usually might.

With its industrial-ugly purity of form, its over-engineered ergonomic perfection, (jeez, I’m sounding like a Jony Ive promotional clip) and its indefensible price tag, this stand represents Apple’s re-commitment to the actual professional user community which the company has all-but-ignored in recent years. And it doesn’t just sit there and hold your monitor for you. The pro stand attaches to the XDR monitor without screws, but with the simple click of some magnets. From there, the stand makes the giant screen infinitely adjustable (and rotatable) with the gentle push of one finger, yet won’t budge when you don’t want it too. It’s a real piece of work.

Here’s the thing. The new Mac Pro and XDR monitor aren’t for you. They aren’t for me. They likely aren’t for anyone you know, and maybe not for anyone the people you know, know. They’re for video/audio/design professionals for whom a $50,000 (or more) workstation setup is a just a typical cost of operations. …

The prosumer in me is, in a way, just as disappointed as those folks at the WWDC who’d been hoping to buy tomorrow’s Mac Pro at yesterday’s prices. What we’ll settle for is getting prosumer performance at what used to be consumer prices.

As for that optional $999 stand, those who actually need it won’t ask the price — and can afford not to. Besides, it’s nice to see Apple finally put the Pro back in Mac Pro, even if there will never be another one on my desktop.

RTWT

20 Sep 2019

Downright frightening.

HT: Karen L. Myers.

18 Jul 2019

What could possibly be better for state surveillance and control? (Logic Magazine)

This summer I spent a month in Beijing. I’d last lived in China in 2016, and I was relieved to find my favorite noodle shops in their usual niches. But this time round, navigating the city felt inexplicably different. The cabs I tried to hail passed me by. On the subway, other riders jostled past me, swiping their phones at the turnstiles as I fumbled with my ticket. When I tried to sneak into the cafeteria in Renmin University for a cheap lunch, clutching my grubby backpack, I made it past the guards only to be stopped at the cash register—apart from student cards, the only form of payment accepted was Alipay.

It gradually dawned on me that that was why Beijing felt like a different city from the one I knew: in the two years since I’d left, the whole city had switched over to mobile payments on China-specific platforms to which I, a foreigner, had no access. These days in Beijing, the green and blue logos of mobile payment providers WeChat Pay and Alipay appear everywhere, from breakfast stalls to five-star hotels.

Just about every foreigner who’s visited China in the last ten years comments on the dizzying speed at which physical infrastructure is built. When I first moved to Shanghai in 2012, I worked in the city’s financial district, home to a skyscraper nicknamed the “bottle openerâ€: according to Wikipedia, it’s the world’s tallest building with a hole in it. But these days, China’s part in the race to build the world’s tallest building appears to be waning. China’s much-vaunted speed in infrastructure building has more recently been directed at the digital rather than the physical world.

RTWT

18 Jun 2019

Nicholas Phillips, at Quillette, delivers up a hearty serving of old-fashioned curmudgeonly skepticism of the benignity of all technological change. No Robotic Communism for him!

When forecasting the future, perhaps the only thing that can be trusted is the emergence of unprecedented, unpredictable events that violate past trends. On the eve of the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis, none of the models used to forecast house prices accounted for the possibility of a price collapse—for the simple reason that no such collapse had ever happened. Price data was historical, and extrapolating that history into the future rendered us blind to the possibility that something ahistorical might happen. Or as Pessimists Archive unwittingly put it: the possibility that “this time it’s different.â€

But techno-optimists take the exercise a step further, by using data about one thing to forecast the future of an entirely different thing. This moves us from the flawed to the absurd. For instance, when techno-optimists compare anxiety over driverless cars to the protests of the horse-and-buggy industry over the automobile, they ignore the ways that driverless cars implicate fundamentally different problems than did automobiles. Driverless cars stand ready to collect immense amounts of personal data about the habits of their passengers, and their networked structure creates serious national security risks. What could the successful debut of the automobile in the early 20th century possibly tell us about that?

The political philosopher Gerald Gaus argues that the less precedent there is for some practice working, the less reason there is to prefer it. In the case of new technologies that implicate brand-new problems, the data we have about the success of past technologies is simply irrelevant. History gives us no reason to prefer a world in which, for example, most manual work is automated. It’s never happened before.

We draw spurious historical analogies precisely because it’s easy. If we can say that Change A is just like Change B, which went fine, it allows us to avoid grappling with the actual qualities of Change A. Argument by analogy displaces argument on the merits. It’s far more convenient to assert that past change was good, present change is just like past change, therefore present change is good too.

Unfortunately, by any objective measure, most new things are bad. People are positively brimming with awful ideas. Ninety percent of startups and 70 percent of small businesses fail. Just 56 percent of patent applications are granted, and over 90 percent of those patents never make any money. Each year, 30,000 new consumer products are brought to market, and 95 percent of them fail. Those innovations that do succeed tend to be the result of an iterative process of trial-and-error involving scores of bad ideas that lead to a single good one, which finally triumphs. Even evolution itself follows this pattern: the vast majority of genetic mutations confer no advantage or are actively harmful. Skepticism towards new ideas turns out to be remarkably well-warranted.

The need for skepticism towards change is just as great when the innovation is social or political. For generations, many progressives embraced Marxism and thought its triumph inevitable. Future generations would view us as foolish for resisting it—just like Thoreau and the telegraph. But it turned out that Marxism was a terrible idea, and resisting it an excellent one. It had that in common with virtually every other utopian ideal in the history of social thought. Humans struggle to identify where precisely the arc of history is pointing.

Techno-optimists would likely prefer to put aside failed products and ideologies and consider instead those innovations that have already proven successful. We’re talking about the iPhone, after all. Is popular adoption of an innovation reason enough to suspend skepticism? No—we turn out to be quite bad at predicting the full impact of even our most successful ideas. Adding lead to gasoline made automobile transportation more efficient, but it caused widespread brain damage and may have been responsible for the 20th century crime boom. Freon in refrigerators punched a hole in the ozone and had to be banned by international compact. Fossil fuels, one of the most successful product innovations in history, are experiencing what might politely be called a re-evaluation.

Another massively successful innovation undergoing a re-evaluation of its own is the internet itself. Optimists promised emancipation: knowledge would be democratized and civil discourse would flourish. Now, we understand that the internet is also a highly effective system of control. Incentives to commodify personal information have resulted in more and more of our daily lives becoming subject to data collection, transforming our economy into a surveillance ecosystem. This renders our conduct “visible†to states, which can punish us for it—as China is doing now through its dystopian “social credit†system. The whole thing could turn out to be a terrible mistake—we don’t know, because we’ve never had to solve this problem before. The fact that we previously solved the problem of the telegraph is irrelevant. One could probably fill a podcast—call it the “Optimists’ Archiveâ€â€”with inappropriately rosy predictions about the wonders of new technology.

We are engaged in a giant social experiment. For 99 percent of the time humans have lived in settled societies, life in each generation was essentially like life in the generation before. Stasis, not change, was the rule. Now, for the first time, we live differently, and the gap between the generations grows wider as the pace of change grows faster. Can this continue indefinitely? We have no precedent for that working. Analogies to history are analogies to nothing at all. We might as well analogize the driverless car to the hand-ax.

Instead of empty analogies, the only way to survive change is to have a vigorous debate about the merits of our new ideas—precisely the kind of debate that techno-optimists want to foreclose by appealing to history. We might ask instead: what does this new thing do to us? Do we understand enough to answer that question? If not, on what basis does our confidence rest? Debate on the merits is essential to distinguishing good ideas from bad ones. And for that, you need the people that techno-optimists most loathe: conservatives.

RTWT

19 Nov 2018

Slate has the story.

When Kurt Luther walked into Pittsburgh’s Heinz History Center in 2013 to attend an exhibition about Pennsylvania during the Civil War, he didn’t expect to be greeted by his great-great-great-uncle. A computer scientist and Civil War enthusiast, Luther had been drawn to researching his own family’s connection to the conflict, gradually piecing together information over years and years. But his searches had always failed to turn up a photograph, and Luther was ready to give up on the possibility of ever seeing his ancestors’ faces. It was only through sheer happenstance that, walking through the History Center that day, Luther had spotted an album of portraits of the men of Company E, 134th Pennsylvania––his great-great-great-uncle’s unit. Laying eyes on his relative’s face for the first time, he later wrote, felt like “closing a gap of 150 years.â€

Five years later, Luther launched Civil War Photo Sleuth, a web platform dedicated to closing the gap a little further. Together with Ron Coddington (editor of the magazine Military Images), Paul Quigley (director of the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies), and a group of student researchers at Virginia Tech, Luther crafted a free and easy-to-use website that applies facial recognition to the multitude of anonymous portraits that survive from the conflict, in the hopes of identifying the sitter. When a user uploads a photograph, the software maps up to 27 distinct “facial landmarks.†Users are further able to refine their searches by adding filters for uniform details that could offer clues about rank. (Three chevrons and a star, for instance, indicates a rank of ordnance sergeant for both the Union and Confederate armies, while shoulder straps with an eagle were worn by Union colonels.) From there, the program cross-references the photo with the other images in CWPS’s growing database. The final search results present an array of possible matches (and possible names) for consideration.

RTWT

It’s all the facial fungus that makes it hard.

22 Oct 2018

I have compiled all the comments on this web-site loading slowly below, so that potential technical support can have a handy reference.

My own observations:

I have no clue what the problem some people (and only some people) seem to be having could be.

I use Chrome for blogging and I look at the blog all the time in Chrome, and it loads normally for me. My wife finds no problem either.

I did reduce the number of posts on page one which should slightly speed things up.

I now intend to ask for technical advice.

———————————-

2018/10/09 at 5:51 pm:

Your website has become really, really slow. Last few days. So slow sometimes I just cancel the load and go somewhere else.

——————

2018/10/11 at 3:03 pm:

Thursday, 10/11, 3:00 p.m. EST: unusable. 1:16 (one minute, 16 seconds) for your page to load once the name resolution completed. Just as long to access this comment page. No problems with any other websites.

——————

2018/10/13 at 9:42 am:

It’s working well now! Much, much better.

I’ve been using both Chrome and Safari on a Mac – operating system and browsers all latest versions. Chrome has been flakey with High Sierra, but the slow load was only your site, until last night.

You can email me to discuss offline if you like, and I’m happy to provide feedback going forward.

——————

2018/10/13 at 5:55 pm:

I spoke too soon. Now, almost 6:00 p.m. Saturday, it’s back to 1:16 from clicking the comment link to the page load.

Something’s very wrong.

——————

2018/10/13 at 10:06 pm:

Update: right now it’s really, really slow on Chrome and Safari, but

speedy on Firefox.

Mac OS X 10.13.6 (High Sierra)

Chrome Version 69.0.3497.100 (Official Build) (64-bit)

Safari Version 12.0 (13606.2.11)

Firefox 62.0.3 (64-bit)

(I believe these are all latest versions)

I can’t explain it.

——————

2018/10/16 at 7:33 am:

I know, it’s weird. I tried it again just now, it seemingly NEVER loads on Safari, and takes forever on Chrome, but it’s speedy with Firefox. As I said, latest Mac OS, latest Chrome, latest Safari, latest Firefox. The browser status when it’s taking a long time is “Connecting….†It eventually connects, but ever page load to your blog takes as long.

I’d really like to know if it’s me, what it is!

——————

2018/10/16 at 12:24 pm:

On Chrome on my home desktop has been loading slowly for a week or two.

——————

2018/10/16 at 11:42 am:

Use Chrome . No issues .

——————

2018/10/16 at 5:23 pm:

on Safari it has stopped loading all together when I click my bookmark. But if I manually type in url it will load. On Chrome it loads very slowly but eventually does load.

——————

2018/10/16 at 5:59 pm:

Usually access using Android phone with Chrome. Has been exceeding slow to load the last couple weeks but is ok after it does.

Tried it with Brave which I recently installed. Handshake took a few seconds but loaded quickly. Never had an issue with Firefox on laptop.

——————

2018/10/16 at 6:50 pm:

It is just fine on Firefox but videos linked from facebook don’t even show on the page.

——————

2018/10/16 at 7:05 pm:

Chrome… about two weeks ago it started to go very slow. Takes about 30 seconds to open the home page. Clicking here just now to comment also took another 30 seconds.

But like the old catsup commercial… anticipation was worth it.

——————

2018/10/19 at 12:44 pm:

Loads like ye olde greased lightning.

03 Oct 2018

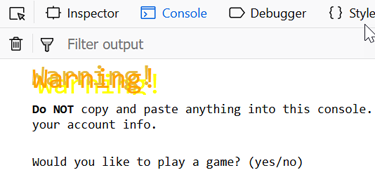

Just type “T-Rex Run” in the Google Search Box.

—————————————-

Type “Text Adventure” into Google Search Box.

Right click on box and select “Inspect.”

Click on “Console” on top of screen.

You should get “Would you like to play a game? yes/no.”

23 Aug 2018

There was a lack of blogging the last two days, as I have been going through the ordeal of installing programs and moving stuff to a new personal computer.

I can remember seeing Jim Dunnigan, my boss at SPI, obsessing out playing with a new TRS-80 way back in 1977.

It’s been 41 long, hard years, folks, and these things are still not an appliance at all. Trying to put a non-Google, Yahoo, or Microsoft email into Outlook is a task on the scale of killing the biggest monster in the last dungeon. You die a lot before you get it.

23 Jun 2018

I was looking through the archives of my blog, looking for a book reference I’d forgotten, when I found this old column from Fred on Everything which demands republishing.

Fred Reed looks at what has become of the American character.

Americans tend to regard their national character as comprising such things as freedom, independence, individualism, and self-reliance…

In fact we no longer have these qualities and probably never will again. Generally we now embody their opposites. Modern society has become a hive of largely conformist, closely regulated and generally helpless employees who depend on others for nearly everything. The cause is less anything particularly American than the technology that governs our lives. The United States just moves faster in the direction in which the civilized world moves.

Character springs from conditions. Consider a farmer in, say, North Carolina in 1850. He was free because there was little government, self-reliant because what he couldn’t do for himself didn’t get done, independent because, apart from a few tools, he made or grew all he needed, and an individualist because, there being little outside authority, he could do as he pleased.

All of that is gone, and will not return. Freedom has given way to an infinite array of laws, rules, regulations, licenses, forms, requirements. Many make sense, may even be desirable in a complex world, don’t necessarily make for a bad life, but they cannot be called freedom. Various governments determine what our children learn, whether we can paint the shutters, who we must sell our houses to, who we can hire, what we can say if we want to keep our jobs, where we can park, and whether and how we can build an outbuilding.

People who live infinitely controlled lives become accustomed to such control. Obedience becomes natural…

Individualism has withered under the pressure of the mass media and a distaste for eccentricity. Self-reliance died long ago. We depend on others to repair our cars, grow our food, fix the refrigerator, and write our operating systems. The habit of reliance on others has reached the point that even the right of self-defense has come to be regarded as wrong-minded…

Most poignantly, we are become a nation of employees, fearful of losing our jobs. Prisoners of the retirement system, afraid of transgressing against the various governing bodies before whom we are helpless, unable to feed ourselves, we are at least comfortable. We are not masters of our lives.

Dense populations and the complexity of machines and institutions lead inevitably to regulation, which leads to acceptance of regulation and therefore of authority, which becomes part of the national character. This we see. In my lifetime the change has been great. In rural Virginia in the Sixties, you could walk down the road with your rifle to shoot beer cans, swim in the creeks without supervision and life guards and “flotation devices” approved by the Coast Guard, and generally be left alone. Now, no. Regimentation has grown like kudzu. We obey. The new generation knows nothing else..

At the moment we see a great increase in regulation in the guise of preventing terrorism. Other pretexts could have been found and, I suspect, would have been: fighting crime or the war on drugs or something. The result might have been a drift rather than a headlong rush toward control. But sooner or later, technology determines politics. The computer, not the Constitution, is primary.

I suspect that the concern about terrorism is just a particular manifestation of a growing obsession with safety. Not too long ago, Americans were a hardy breed—foolhardy at times, but the one comes with the other. Now we see attempts to eliminate all risk everywhere. Cities fill in the deep ends of swimming pools and remove diving boards. We require that bicyclists wear helmets, fear second-hand smoke and the violence that is dodge ball. Warnings abound against going outside without sun block. To anyone who grew up in the Sixties or before, the new fearfulness is incomprehensible.

The explanation I think is the feminization of society, which seems to be inseparable from modernity. The nature of masculinity is to prize freedom over security; of femininity, security over freedom. Add that the American character of today powerfully favors regulation by the group in preference to individual choice. Note that we do not require that cars be equipped with seat belts and then let individuals decide whether to use them; we enforce their use. The result is compulsory Mommyism, very much a part of today’s America.

Does technological civilization inevitably lead to totalitarianism? Certainly the general fear, in combination with technology, makes a sort of soft Stalinism easy. Just now we move toward national ID cards, smuggled in by linking records of drivers’ licenses. Passports, scanned and linked to data bases, provide a record of our travels. Security cameras proliferate. Some of them read the license plates of all passing cars. Email can be monitored, phones easily and undetectably tapped. Now the government is experimenting with X-ray scanners for airports that provide near-pornographic images of passengers. Whether these will be used for dictatorial ends remains to be seen. Historians may one day note that surveillance, when possible, is inevitable.

What then is the national character today? I think we are first an obedient people. We submit. We are comfortable with authority, and seem to be most comfortable when we are told what to do. We prize security, safety, and predictability. Increasingly we accept being treated like convicts at airports and elsewhere. We want to be taken care of. We can do few things for ourselves. We expect government to decide much that was once regarded as outside of government’s ambit. And we are to the marrow of our bones incapable of rising against the creeping tyranny.

Too bloody true, alas!

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Technology' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|