Archive for April, 2017

25 Apr 2017

Plato’s Chariot Metaphor as sculpture.

Plato, in the Phaedrus, conceives of the soul as having three parts: A rational part (the part that loves truth and knowledge, which should rule over the other parts of the soul through the use of reason). The Charioteer represents man’s Reason. A spirited part (which seeks glory, honor, recognition and victory). The white horse represents man’s spirit (thymos:θÏμος). An appetitive part (which desires food, drink, material wealth and sex). The black horse represents man’s appetites.

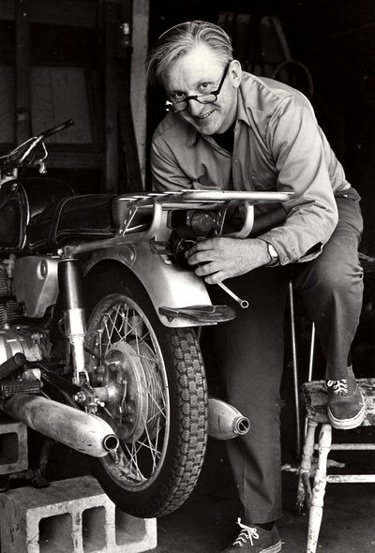

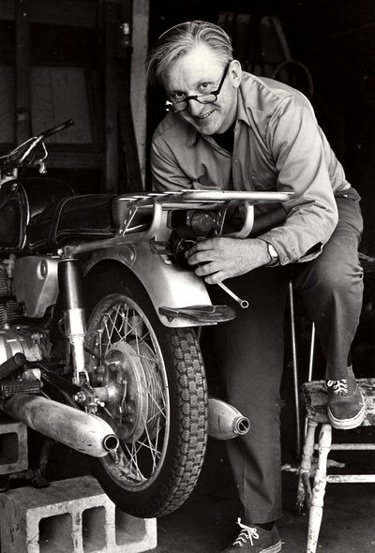

Robert M. Pirsig died yesterday.

Recovering from a nervous breakdown, Pirsig, back in the 1970s, crafted a brilliant book memorializing his own deceased former personality (referred to in the third person as “Phaedrus”), and dispensing Buddhistic enlightenment mixed with Plato in the course of a grand road trip. His title was a clever take-off from the 1953 surprise best-seller Zen in the Art of Archery by Eugene Herrigel, a landmark classic in the 1950s Beats’ love affair with Zen.

NPR wrote:

Robert M. Pirsig, who inspired generations to road trip across America with his “novelistic autobigraphy,” Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, died Monday at the age of 88.

His publisher William Morrow & Company said in a statement that Pirsig died at his home in South Berwick, Maine, “after a period of failing health.” …

Zen was published in 1974, after being rejected by 121 publishing houses. “The book is brilliant beyond belief,” wrote Morrow editor James Landis before publication. “It is probably a work of genius and will, I’ll wager, attain classic status.”

Indeed, the book quickly became a best-seller, and has proved enduring as a work of popular philosophy. A 1968 motorcycle trip across the West with his son Christopher was his inspiration.

Christopher Lehmann-Haupt reviewed Zen for The New York Times in 1974. “[H]owever impressive are the seductive powers with which Mr. Pirsig engages us in his motorcycle trip, they are nothing compared to the skill with which he interests us in his philosophic trip,” he wrote. “Mr. Pirsig may sometimes appear to be a greenerâ€America proselytizer, with his beard and his motorcycle tripping and his talk about learning to love technology. But when he comes to grips with the hard philosophical conundrums raised by the 1960’s, he can be electrifying.”

Pirsig was born in Minneapolis, the son of a University of Minnesota law professor. He graduated from high school at 15 and enlisted in the Army after World War II. While stationed in South Korea, he encountered the Asian philosophies that would underpin his work. He went on to study Hindu philosophy in India and for a time was enrolled in a philosophy Ph.D. program at the University of Chicago. He was hospitalized for mental illness and returned to Minneapolis, where he worked as a technical writer and began writing his first book.

A quotation from ZAMM:

That’s all the motorcycle is, a system of concepts worked out in steel. There’s no part in it, no shape in it, that is not out of someone’s mind. …

I’ve noticed that people who have never worked with steel have trouble seeing this—that the motorcycle is primarily a mental phenomenon. They associate metal with given shapes—pipes, rods, girders, tools, parts—all of them fixed and inviolable, and think of it as primarily physical. But a person who does machining or foundry work or forge work or welding sees “steel” as having no shape at all. Steel can be any shape you want if you are skilled enough, and any shape but the one you want if you are not. …

These shapes are all out of someone’s mind. That’s important to see. The steel? Hell, even the steel is out of someone’s mind. There’s no steel in nature. Anyone from the Bronze Age could have told you that. All nature has is a potential for steel. There’s nothing else there. But what’s “potential”? That’s also in someone’s mind!

24 Apr 2017

“You all start with the premise that democracy is some good. I don’t think it’s worth a damn. Churchill is right. The only thing to be said for democracy is that there is nothing else that’s any better. …

“People say, ‘If the Congress were more representative of the people it would be better.’ I say Congress is too damn representative. It’s just as stupid as the people are, just as uneducated, just as dumb, just as selfish.â€

24 Apr 2017

T.A. Frank, in Vanity Fair, totally demolishes the third member of the Clinton Dynasty.

Like tribesmen laying out a sacrifice to placate King Kong, news outlets continue to make offerings to the Clinton gods. In The New York Times alone, Chelsea has starred in multiple features over the past few months: for her tweeting (it’s become “feistyâ€), for her upcoming book (to be titled She Persisted), and her reading habits (she says she has an “embarrassingly large†collection of books on her Kindle). With Chelsea’s 2015 book, It’s Your World, now out in paperback, the puff pieces in other outlets—Elle, People, etc.—are too numerous to count.

One wishes to calm these publications: You can stop this now. Haven’t you heard that the great Kong is no more? Nevertheless, they’ve persisted. At great cost: increased Chelsea exposure is tied closely to political despair and, in especially intense cases, the bulk purchasing of MAGA hats. So let’s review: How did Chelsea become such a threat?

Perhaps the best way to start is by revisiting some of Chelsea’s major post-2008 forays into the public eye. Starting in 2012, she began to allow glossy magazines to profile her, and she picked up speed in the years that followed. The results were all friendly in aim, and yet the picture that kept emerging from the growing pile of Chelsea quotations was that of a person accustomed to courtiers nodding their heads raptly. Here are Chelsea’s thoughts on returning to red meat in her diet: “I’m a big believer in listening to my body’s cravings.†On her time in the “fiercely meritocratic†workplace of Wall Street: “I was curious if I could care about [money] on some fundamental level, and I couldn’t.†On her precocity: “They told me that my father had learned to read when he was three. So, of course, I thought I had to too. The first thing I learned to read was the newspaper.†Take that, Click, Clack, Moo.

Chelsea, people were quietly starting to observe, had a tendency to talk a lot, and at length, not least about Chelsea. But you couldn’t interrupt, not even if you’re on TV at NBC, where she was earning $600,000 a year at the time. “When you are with Chelsea, you really need to allow her to finish,†Jay Kernis, one of Clinton’s segment producers at NBC, told Vogue. “She’s not used to being interrupted that way.â€

Sounds perfect for a dating profile: I speak at length, and you really need to let me finish. I’m not used to interruptions.

What comes across with Chelsea, for lack of a gentler word, is self-regard of an unusual intensity. And the effect is stronger on paper. Unkind as it is to say, reading anything by Chelsea Clinton—tweets, interviews, books—is best compared to taking in spoonfuls of plain oatmeal that, periodically, conceal a toenail clipping.

RTWT

24 Apr 2017

Luis Jiménez y Aranda, Los bibliófilos, 1880

23 Apr 2017

Hans von Aachen, St. George Slaying the Dragon, c. 1600, Private Collection, London

From Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, 1869:

Butler, the historian of the Romish calendar, repudiates George of Cappadocia, and will have it that the famous saint was born of noble Christian parents, that he entered the army, and rose to a high grade in its ranks, until the persecution of his co-religionists by Diocletian compelled him to throw up his commission, and upbraid the emperor for his cruelty, by which bold conduct he lost his head and won his saintship. Whatever the real character of St. George might have been, he was held in great honour in England from a very early period. While in the calendars of the Greek and Latin churches he shared the twenty-third of April with other saints, a Saxon Martyrology declares the day dedicated to him alone; and after the Conquest his festival was celebrated after the approved fashion of Englishmen.

In 1344, this feast was made memorable by the creation of the noble Order of St. George, or the Blue Garter, the institution being inaugurated by a grand joust, in which forty of England’s best and bravest knights held the lists against the foreign chivalry attracted by the proclamation of the challenge through France, Burgundy, Hainault, Brabant, Flanders, and Germany. In the first year of the reign of Henry V, a council held at London decreed, at the instance of the king himself, that henceforth the feast of St. George should be observed by a double service; and for many years the festival was kept with great splendour at Windsor and other towns. Shakspeare, in Henry VI, makes the Regent Bedford say, on receiving the news of disasters in France:

Bonfires in France I am forthwith to make

To keep our great St. George’s feast withal!’

Edward VI promulgated certain statutes severing the connection between the ‘noble order’ and the saint; but on his death, Mary at once abrogated them as ‘impertinent, and tending to novelty.’ The festival continued to be observed until 1567, when, the ceremonies being thought incompatible with the reformed religion, Elizabeth ordered its discontinuance. James I, however, kept the 23rd of April to some extent, and the revival of the feast in all its glories was only prevented by the Civil War. So late as 1614, it was the custom for fashionable gentlemen to wear blue coats on St. George’s day, probably in imitation of the blue mantle worn by the Knights of the Garter.

In olden times, the standard of St. George was borne before our English kings in battle, and his name was the rallying cry of English warriors. According to Shakspeare, Henry V led the attack on Harfleur to the battle-cry of ‘God for Harry! England! and St. George!’ and ‘God and St. George’ was Talbot’s slogan on the fatal field of Patay. Edward of Wales exhorts his peace-loving parents to

‘Cheer these noble lords,

And hearten those that fight in your defence;

Unsheath your sword, good father, cry St. George!’

The fiery Richard invokes the same saint, and his rival can think of no better name to excite the ardour of his adherents:

‘Advance our standards, set upon our foes,

Our ancient word of courage, fair St. George,

Inspire us with the spleen of fiery dragons.’

England was not the only nation that fought under the banner of St. George, nor was the Order of the Garter the only chivalric institution in his honour. Sicily, Arragon, Valencia, Genoa, Malta, Barcelona, looked up to him as their guardian saint; and as to knightly orders bearing his name, a Venetian Order of St. George was created in 1200, a Spanish in 1317, an Austrian in 1470, a Genoese in 1472, and a Roman in 1492, to say nothing of the more modern ones of Bavaria (1729), Russia (1767), and Hanover (1839).

Legendarily the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George was founded by the Emperor Constantine (312-337 A.D.). On the factual level, the Constantinian Order is known to have functioned militarily in the Balkans in the 15th century against the Turk under the authority of descendants of the twelfth-century Byzantine Emperor Isaac II Angelus Comnenus.

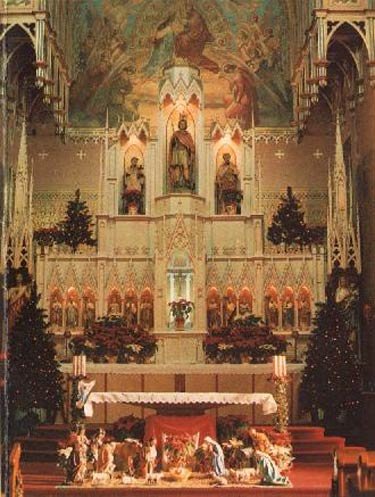

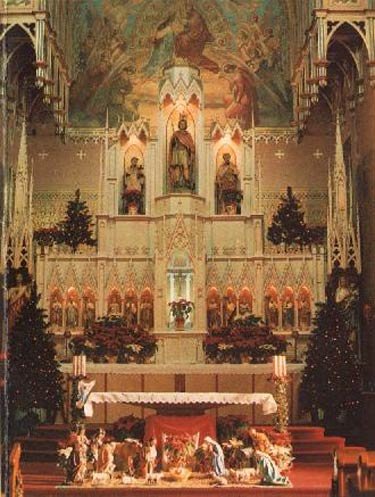

We Lithuanians liked St. George as well. When I was a boy I attended St. George Lithuanian Parish Elementary School, and served mass at St. George Lithuanian Roman Catholic Church in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania.

St. George Church, Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, Christmas, 1979. This church, built by immigrant coal miners in 1891, was torn down by the Diocese of Allentown in 2010.

23 Apr 2017

The New York Post points out that, but for the publication of his plays in the First Folio by his friends Heminges and Condell, half the plays that came down to us could have been lost.

April 23 marks the [401]th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare. The world will celebrate him as the greatest writer in the history of the English language. But his lasting fame wasn’t inevitable. It almost did not happen.

He was born in 1564 and died in 1616 on his 52nd birthday. A celebrated writer and actor who had performed for Queen Elizabeth and King James, he wrote approximately 39 plays and composed five long poems and 154 sonnets. By the time of his death, he had retired and was considered past his prime.

By the 1620s, his plays were no longer being performed in theaters. On the day he died, no one — not even Shakespeare himself — believed that his works would last, that he was a genius or that future generations would hail his writings.

He hadn’t even published his plays — during his lifetime they were considered ephemeral amusements, not serious literature. Half of them had never been published in any form and the rest had appeared only in unauthorized, pirated versions that corrupted his original language.

Enter John Heminges and Henry Condell, two of Shakespeare’s friends, fellow actors and shareholders in the King’s Men theatrical company. In his will he left them money to buy gold memorial rings to remember him. By about 1620, they conceived a better way to honor him — one that would make them the two most unsung heroes in the history of English literature. They would do what Shakespeare had never done for himself — publish a complete, definitive collection of his plays.

Heminges and Condell had up to six types of sources available to them: Shakespeare’s original, handwritten drafts; manuscript “prompt books†copied from the drafts; fragment “sides†used by the actors and containing only the lines for their individual parts; printed quartos — cheap paperbound booklets — that published unauthorized and often wildly inaccurate versions of half the plays; after-the-fact memorial reconstructions by actors who had performed in the plays and later repeated their lines to a scribe hired by Heminges and Condell; and the editors’ own personal memories.

Today, no first-generation sources for the plays exist. None of Shakespeare’s original, handwritten manuscripts survive — not a play, act, scene, page of dialogue or even a sentence. Without Heminges and Condell, half of the plays would have been lost forever.

They got to work after the bard’s death. At the London print shop Jaggard & Son, workers set the type by hand, printed the sheets one by one and hung them on clotheslines for the ink to dry. The process was methodical and slow, done by hand. It took two years.

When at last the First Folio was finished, it was a physically impressive object. At more than 900 pages, it had size and heft. The tallest copies, right off the press, untrimmed by the printer’s plow, measured 13½ by 8¾ inches.

Published in London in 1623, “Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories & Tragedies†revolutionized the language, psychology and culture of Western civilization. Without the First Folio, published seven years after the bard’s death, 18 iconic works — including “Macbeth,†“Measure for Measure,†“Julius Caesar,†“Antony and Cleopatra,†“Twelfth Night,†“The Winter’s Tale†and “The Tempest†— would have been lost. …

Without the First Folio, his evolution from poet to secular saint would never have happened. The story of that book is an incredible tale of faith, friendship, loyalty and chance. Few people realize how close the world came, in the aftermath of Shakespeare’s death, to losing him.

Today, it is one of the most valuable books in the world. In October 2001, one of them sold for more than $6 million. Of the 750 copies printed, two-thirds of them have perished over the last 393 years. Two hundred thirty-five survive.

22 Apr 2017

Researchers conducting a surface survey mark the locations of stone flakes, points, and tools brightly colored flags. Researchers conducting a surface survey mark the locations of stone flakes, points, and tools brightly colored flags.

The New York Post reports on the discovery in Kansas of a lost 16th century Indian metropolis.

A long lost 16th century civilization has been unearthed in rural Kansas — all thanks to a plucky teen who helped archaeologists confirm the incredible discovery.

The metropolis — where up to 20,000 Wichita Indians once lived — was discovered in Arkansas City, in the south-central part of the state, when a high school boy found a cannon ball that tipped off the experts that their long-held suspicions about the existence of Etzanoa were correct, the Kansas City Star reported.

The city, whose name means “The Great Settlement,†is believed to be the second-largest Native American city in the US and was the site of a battle between Spanish explorers and Indian warriors in 1601.

“The Spaniards were amazed by the size of Etzanoa,†according to Donald Blakeslee, a 73-year-old Wichita State University archaeologist, who announced the discovery.

“They counted 2,000 houses that could hold 10 people each. They said it would take two or three days to walk through it all,†said Blakeslee, adding that the patch of land spans thousands of acres.

For years, he and other scientists hunted for the fabled city. They dug up pottery, knives and flint tools and toiled over clues that would link it to records from Spanish explorers — but couldn’t confirm that it was Etzanoa.

Then last year, Adam Ziegler, who attends a nearby high school, discovered a half-inch iron cannon ball — linking it to the 1601 battle, according to Blakeslee.

During the combat, Spaniards fired cannons at Wichita Nation Indian warriors, who eventually fled the city.

22 Apr 2017

Christopher Caldwell, in City Journal, discusses the untranslated three-book oeuvre of French commentator Christophe Guilluy, a specialist observer of French demographics, real estate, and economic developments, who describes the development, in France, of a similar practical separation and conflict of interests between the prosperous urban community of fashion elite and La France périphérique, the Gallic equivalent of Fly-Over America.

[T]he urban real-estate market is a pitiless sorting machine. Rich people and up-and-comers buy the private housing stock in desirable cities and thereby bid up its cost. Guilluy notes that one real-estate agent on the Île Saint-Louis in Paris now sells “lofts†of three square meters, or about 30 square feet, for €50,000. The situation resembles that in London, where, according to Le Monde, the average monthly rent (£2,580) now exceeds the average monthly salary (£2,300).

The laid-off, the less educated, the mistrained—all must rebuild their lives in what Guilluy calls (in the title of his second book) La France périphérique. This is the key term in Guilluy’s sociological vocabulary, and much misunderstood in France, so it is worth clarifying: it is neither a synonym for the boondocks nor a measure of distance from the city center. (Most of France’s small cities, in fact, are in la France périphérique.) Rather, the term measures distance from the functioning parts of the global economy. France’s best-performing urban nodes have arguably never been richer or better-stocked with cultural and retail amenities. But too few such places exist to carry a national economy. When France’s was a national economy, its median workers were well compensated and well protected from illness, age, and other vicissitudes. In a knowledge economy, these workers have largely been exiled from the places where the economy still functions. They have been replaced by immigrants. …

Top executives (at 54 percent) are content with the current number of migrants in France. But only 38 percent of mid-level professionals, 27 percent of laborers, and 23 percent of clerical workers feel similarly. As for the migrants themselves (whose views are seldom taken into account in French immigration discussions), living in Paris instead of Boumako is a windfall even under the worst of circumstances. In certain respects, migrants actually have it better than natives, Guilluy stresses. He is not referring to affirmative action. Inhabitants of government-designated “sensitive urban zones†(ZUS) do receive special benefits these days. But since the French cherish equality of citizenship as a political ideal, racial preferences in hiring and education took much longer to be imposed than in other countries. They’ve been operational for little more than a decade. A more important advantage, as geographer Guilluy sees it, is that immigrants living in the urban slums, despite appearances, remain “in the arena.†They are near public transportation, schools, and a real job market that might have hundreds of thousands of vacancies. At a time when rural France is getting more sedentary, the ZUS are the places in France that enjoy the most residential mobility: it’s better in the banlieues.

In France, the Parti Socialiste, like the Democratic Party in the U.S. or Labour in Britain, has remade itself based on a recognition of this new demographic and political reality. François Hollande built his 2012 presidential victory on a strategy outlined in October 2011 by Bruno Jeanbart and the late Olivier Ferrand of the Socialist think tank Terra Nova. Largely because of cultural questions, the authors warned, the working class no longer voted for the Left. The consultants suggested a replacement coalition of ethnic minorities, people with advanced degrees (usually prospering in new-economy jobs), women, youths, and non-Catholics—a French version of the Obama bloc. It did not make up, in itself, an electoral majority, but it possessed sufficient cultural power to attract one.

It is only too easy to see why a populist and nationalist revolt against the elite urban community of fashion is an international development.

A must-read.

22 Apr 2017

Topping out photo of the crew who erected the spire of the Wiltshire Grand Hotel in Los Angeles, September 7, 2016, 1000′ above the city streets.

/div>

Feeds

|