Archive for April, 2020

29 Apr 2020

How can a remote place like Matanuska-Susitna, Alaska gain the attention of the rest of the world? Why, it need merely elect a school board and turn the bozos loose to make micromanaging curriculum decisions. NBC News.

An Alaska school board removed five famous — but allegedly “controversial” — books from district classrooms, inadvertently spurring renewed local interest in the excluded works.

“I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” by Maya Angelou, “Catch-22” by Joseph Heller, “The Things They Carried” by Tim O’Brien, “The Great Gatsby” by F. Scott Fitzgerald, and “Invisible Man” by Ralph Ellison were all taken off an approved list of works that teachers in the Mat-Su Borough School District may use for instruction.

The school board voted 5-2 on Wednesday to yank those works out of teachers’ hands starting this fall. The removed books contained content that could potentially harm students, school board vice president Jim Hart told NBC News on Tuesday.

“If I were to read these in a corporate environment, in an office environment, I would be dragged into EO,” an equal opportunity complaint proceeding, Hart said. “The question is why this is acceptable in one environment and not another.”

“Caged Bird” was derided for “‘anti-white’ messaging,” “Gatsby” and “Things” are loaded with “sexual references,” “Invisible” has bad language and “Catch” contains violence, according to the school district.

Dianne K. Shibe, president of the Mat-Su Education Association teachers union, said parents and her members were stunned by the board action.

Even though the school board had listed an agenda item to discuss “controversial book descriptions,” Shibe said no one believed those works were under serious threat.

RTWT

29 Apr 2020

John William Waterhouse, A Tale From the Decameron, 1916, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Liverpool.

Paula Findlen, in Boston Review, remembers an earlier, far more terrible pandemic, which at least resulted in the creation of an enduring literary classic.

We know the plague best, of course, through the lens of the Black Death, the infamous outbreak of plague that peaked in the mid fourteenth century. The scourge affected most of Eurasia and North Africa, and may have reached as far as sub-Saharan Africa and the Indian Ocean. But some of the most vivid documentation of the devastation it wrought comes from European cities such as Florence, where the fourteenth-century humanist Giovanni Boccaccio had a front-row seat to the most fatal pandemic in recorded human history. There the Black Death left its mark on everything to such a degree that one could speak of a time before plague, and a time after. …

In 1348 Boccaccio’s world changed abruptly and dramatically. The illegitimate son of a wealthy Florentine merchant, he was a struggling writer and sometime commercial agent in his mid-thirties, desperately trying to establish his independence from his father and hoping that he had mostly left Florence behind. He was probably not there but when the “deadly pestilence†arrived in his native city but returned in the aftermath. At least a third of the population died, including his father and stepmother, leaving him to deal with the chaos of lives interrupted.

Boccaccio immediately began to write about his experience as a creative response to this blighted landscape. He most likely completed the Decameron—one hundred tales told by seven young women and three men who fled the city—in 1351. As the title suggests, the collection is a ten-day StorySlam, a verbal marathon racing through the full spectrum of human behavior: aristocratic pretensions, clerical failings, romantic misalliances, corrupt institutions, business deals and marriages gone bad, Christians interacting with Jews and Muslims, peasants wondering if they might ever best their lords. Boccaccio populated his tales with characters from every walk of life. Even today, he remains one of the most articulate and thoughtful eyewitnesses to a society living with a pandemic.

The literary masterpiece begins with an introduction recalling the “painful memory of the deadly havoc wrought by the recent plague.†A keen observer of society, Boccaccio noted how quickly trust broke down, even among friends and neighbors, as the fourteenth-century equivalent of social distancing altered and strained normal relations.

Fear overtook people and found its expression in a number of ways. Boccaccio lamented how many people died alone or among strangers. He documented changes in burial practices, noting that people no longer mourned as they used to because they could not gather publicly or embrace the body of a beloved relative or friend who had succumbed to disease. Ordinary activities became a source of enormous anxiety, as people realized that everything they encountered in their daily lives might harbor infection. Notaries saw business increase, as people obsessively made wills on the chance that they might not survive. Once disease penetrated and altered the social fabric of the city, this corporate body struggled to maintain its integrity.

The Decameron also reflects how imperfectly the state intervened—something Boccaccio understood very well; his recently deceased father was the aptly named Orwellian “Officer of Plenty†(Ufficiale dell’Abbondanza) in charge of reserve supplies. Grain mattered, toilet paper not at all. Ad hoc committees enacted emergency measures, claiming extraordinary powers beyond the normal rule of law, as they also did in times of war.

Unlike COVID-19, bubonic plague is not transmitted by human contact but by fleas and the animals bearing them—unless you were a surgeon lancing buboes or otherwise had direct contact with the site of infection. Renaissance Florentines did not know how this disease worked. Physicians initially took the cause to be the hot humid air of the city in summer. Compared to quarantine, which actually harbored the possibility of preventing infected goods and rodents from entering the city, improvised measures to isolate the sick by immuring them in their homes did little to slow the terrifying course of disease.

Widespread fear became a basis for further mistreatment of the poor, foreign, and disenfranchised sectors of society—those who did not have the luxury of flight. Were they the source of the poisonous air? Previous generations believed that heretics, Jews, and lepers could kill with their breath. That pestilential idea inspired moral explanations of this new disease and fear-ridden efforts to rid society of its impure elements—not in Florence, but in parts of Spain, England, and Northern Europe where religious and economic tensions predated the arrival of plague.

Instead, the more pious Florentines prayed. The clergy who did not flee to save themselves remained to save others, alternately exhorting people to their best behavior and chastising them for being the cause of it all. Thwarting the state, defiant preachers convened the faithful since it was impossible to imagine a good end without divine recourse. Of course business ground to a halt. Commerce between peoples and regions virtually ceased, save for those bold and foolhardy enough to take the risks and suffer the consequences.

Taking the pulse of his society, Boccaccio discerned four principal reactions to a pandemic. First were those who “lived in isolation from everyone else,†who appeared to him a rather self-satisfied, if stoic lot. Their pantries were full of “delicate foods and precious winesâ€; they lightly entertained themselves and simply shut their doors on the world until plague passed. They constantly congratulated themselves on responding well. By contrast, society’s epicureans partied from dawn until dusk, treating plague as “one enormous joke.†They were smart enough to avoid contact with the sick but considered the pandemic a reason to flout all rules.

In between lay a third group of people who did not self-quarantine, soberly or riotously, but carefully moved about the city taking precautionary measures. Long before the modern face mask became a competitive sport for those inclined to make do-it-yourself YouTube videos, fragrant flowers, aromatic herbs, and exotic spices became popular adornments for those dangerous forays outdoors, since they allegedly kept the miasmas of disease at bay. A final group avoided all these problems and fled for the relative isolation and fresh air of the countryside, much like the ten youthful protagonists of his Decameron. Boccaccio observed that all of them lived and died in equal measure, unlike the poor who had no choices and were disproportionately afflicted.

For Boccaccio and his contemporaries, plague became the ultimate test of the fine line between knowledge and ignorance, truth and deception, as much as it also defined the limits of greed and compassion. Famous physicians deployed the full might of their expertise, offering a dizzying array of contradictory explanations—fantastically elaborate astrological charts and complex medical theories of humoral balance and imbalance, bolstered by the weight of authority and learning. They did not have a theory of contagion. Instead, the most perceptive medical practitioners who cared for the sick and dying concluded that the best medicine came from experience, which was initially in short supply. Far more humble healers and those who considered healing an act of pious charity risked their lives to alleviate suffering. Charlatans promising false hope preyed on people’s desperation. Physicians and apothecaries furiously recalibrated recipes for legendary antidotes in the ancient pharmacopeia to ward off poisons in the hope that they might work on something new. No one initially could provide anything remotely like a cure.

Instead, everyone became proficient at recognizing the symptoms, which Boccaccio describes in gruesome and precise detail, finding the right words because it was a shared experience. His telling observation that the Florentine plague “did not take the form it had assumed in the East†is a reminder that we do not have to await the modern era to be aware that a disease is not one thing but a complex of different symptoms that might evolve and change as they migrate with humans, animals, and insects. Even though his society did not understand the means of transmission, people observed its manifestations closely.

Boccaccio not only knew that plague had been something different before it reached Florence; he also understood that “the symptoms of the disease changed†as it evolved between spring and summer within the city. Bubonic plague probably gave way to the pneumonic and septicemic versions—and we might add, surely, the gastrointestinal version if people ate infected animals. Now one could become sick if someone coughed up blood in proximity to a healthy individual, and everyone took note of this awful development. Understanding disease became a project of society as a whole, not simply those who claimed particular expertise or authority. This was a lesson that Boccaccio inscribed in the introduction to the Decameron, which is why his brief but compelling description remains one of the best accounts of this disease, written by a layperson rather than a physician. (Daniel Defoe similarly captured the sheer awfulness of the Great Plague of London a little over three centuries later.)

By the time Boccaccio completed the Decameron, physicians began to write down what they learned, too. He became one of their most attentive and critical readers. While plague initially revealed the inadequacies of fourteenth-century medicine, it also challenged physicians to offer better advice and attempt different solutions in the coming years. They began to think about what kind of poison a plague might be, the first step toward a model of contagion. None of their preventive measures eradicated plague, to be sure, but they helped to establish a new partnership between medical practitioners and the state in devising public health measures, at first temporary and later semi-permanent. Boccaccio was among the first to publicize the changing response to disease.

Despite plague’s virulence, Boccaccio did not leave his readers without hope. With bitter irony, he declared that in the long march of human history, plague had been a “brief unpleasantnessâ€â€”short in duration, long in impact. He lived to see his society emerge from the scourge and later saw it return. In 1351, however, he was cautiously optimistic that better preparedness in the future could lessen the high mortality rate of 1348. “A great many people died who would perhaps have survived had they received some assistance,†he concluded.

RTWT

29 Apr 2020

State solutions are imposed from above; they are often without corrective devices, and cannot easily be reversed on the proof of failure. Their inflexibility goes hand in hand with their planned and goal-directed nature, and when they fail, the efforts of the state are directed not to changing them but to changing people’s belief that they have failed.

-– Roger Scruton

28 Apr 2020

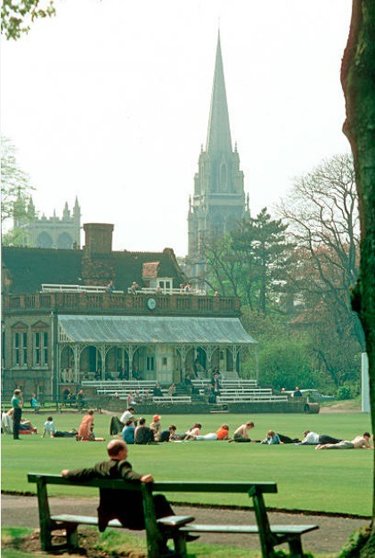

The old Victorian pavilion at Fenner’s in Cambridge during a match between Cambridge University and Yorkshire, 6th May 1970, by Patrick Eagar.

28 Apr 2020

click on image for larger version.

Roman ring, with portrait of Cæsonia Milonia (died 24 January 41), the fourth and last wife of Roman emperor Caligula and a former priestess of the Egyptian goddess Isis. Caesonia had a bad reputation, as she was promiscuous, extravagant, deep in debt, and a divorcee, but Caligula decided to marry her so that she could produce him an heir. She was murdered along with Caligula and their three daughters in 41.

Cut sapphire (and intaglio representing the profile of the empress) and hollowed out and set in gold, early 1st century.

(Former collection of the Dukes of Marlborough, this exceptional ring was sold in October 2019 in London by London jeweler Wartski to an unknown buyer (estimated transaction £ 500,000 / € 570,000 — $ 622,145 / $ 709,245.30).

27 Apr 2020

This last photo of Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen (2 May 1892 – 21 April 1918), known in English as Baron von Richthofen, and most famously as the “Red Baron,” shows him playing with his beloved Great Dane, Moritz, just moments before he embarked on his last flight.

Arthur Roy Brown, the man who shot him down, wrote:

“… the sight of Richthofen as I walked closer gave me a start. He appeared so small to me, so delicate. He looked so friendly. Blond, silk-soft hair, like that of a child, fell from the broad, high forehead. His face, particularly peaceful, had an expression of gentleness and goodness, of refinement. Suddenly I felt miserable, desperately unhappy, as if I had committed an injustice. With a feeling of shame, a kind of anger against myself moved in my thoughts, that I had forced him to lay there. And in my heart I cursed the force that is devoted to death. I gnashed my teeth, I cursed the war. If I could I would gladly have brought him back to life, but that is somewhat different than shooting a gun. I could no longer look him in the face. I went away. I did not feel like a victor. There was a lump in my throat. If he had been my dearest friend, I could not have felt greater sorrow.â€

Freiherr Manfred Albrecht von Richthofen was given a full military burial by No. 3 Squadron Australian Flying Corps, which included a memorial wreath inscribed with the words,“To Our Gallant and Worthy Foe.â€

(via sternvonafrika)

27 Apr 2020

Ornamental Plaque of a Knight, ca. 1300, possibly British, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

My guess would be German, because of the antler crests.

27 Apr 2020

Everyone is doing Peter Beard obituaries. Here is a good one by Elsa Cau from Les Grandes Ducs. (translated from the French.)

Socialite and partygoer, artist, photographer, friend of all, lady’s man, Peter Beard was a passionate and brilliant personality with many parts. He died last Sunday at the age of 80 [JDZ: Actually, Peter Beard was found dead April 19th at the age of 82, having disappeared from his Montauk house on March 31st.] leaving behind a completed oeuvre, an ode to freedom in all its forms, the self-portrait – in selected pieces – of someone wild and real.

We all know the moments. Those perfect moments, the storied instant with a good alignment of the planets, of their ideal conjunction. Put the same people in the same place, at the same time, and hold your breath, and you will still never get the same moment again. In That Summer (2017), the voiceovers of Peter Beard and Lee Radziwill tell us about such an absolute moment.

It was the Summer of 1972. In the photographer’s house in Montauk, their feet in the water, they are all there, smiling, radiant: Andy Warhol, the friend with whom Beard had so much artistic interaction since the 1960s; Mick Jagger, whom he had just followed on tour for two months with the Rolling Stones for the eponymous magazine, and his wife Bianca; the tormented and flamboyant writer Truman Capote, whom he met at the same time; the sisters Lee Radziwill – an old love, a friend until the end – and Jackie Kennedy Onassis.

The almost eighty-year-old photographer lovingly flipped through the pages of the album in his studio in Montauk where he was still working until the end. “Accidents are very important,†he whispered.

And accidents seems to have played a key role in the turbulent existence of Peter Beard. He was born in 1938 of blue American blood (the grandson of railroad tycoon James Jerome Hill) in New York. He was given as a child a camera which would never leave him, and which gave him his obsession with capturing those around him and his observations. A few private schools, a Yale art degree later [JDZ: actually, he was Yale Class of 1961, but never bothered to graduate.], and he’s was free as air.

While still a student, he started working for Vogue. At 17, he traveled for the first time to Africa: it was love at first sight – aren’t these things always an accident? He returned there regularly. It was just then, in the early 1960s, that Peter Beard became friends with Karen Blixen (authoress of Out of Africa, published under her pen name Isak Dinesen), so much so that he purchased land bordering her former farm in Kenya.

What does the youth do when he is beautiful, radiant, and rich? He lives, he loves. Peter Beard excelled at both and everyone who frequented his society has captivated memories of the man. From Studio 54 to the wilds of Kenya, Beard was one of those who feel at ease everywhere, bond with everyone with a smile, a joke, or a dance, and better, can draw you into sharing their own passions.

In the early 1960s, Beard met Dali. The two men laughed at the same pranks and quickly become friends. Around the same time, Francis Bacon became impressed by the photographs of Peter Beard published in The End of the Game, documenting the gradual disappearance of elephants, hippos and rhinos in Africa. The two men met, appreciate one another, and became close friends. These were only two examples among so many friends, there were so many.

Love, too. After his first marriage to Minnie Cushing, a pretty socialite friend and assistant to Oscar de La Renta, which lasted three years, the handsome photographer went on to so many conquests that they became clichés. Minnie still left her mark: six months without sleep, a short stay in a psychiatric hospital after an overdose of barbiturates, but then he was back on his feet. A minor incident! Candice Bergen, Barbara Allen the Warholian muse, Carole Bouquet in her James Bond period, the model Cheryl Tiegs to whom he was married for a few years, Nejma, his last wife, his unfailing support (who turned a blind eye to his other liaisons), the list goes on.

And they are also animals, essentially, Beard’s women (one recalls Iman, that he was the first to discover and use as a model), it is that which he loved, that he photographed, and which inspires him. Stretched, elongated, hanging from liana vines next to antelopes, cheetahs or giraffes, with intense gazes and the deportment of queens, they are just as fundamental to his photographic work as the animals themselves. Since the early 1970s, moreover, he had united his two passions with a mixture of modified photographs, writings and collages.

But ultimately, these two passions were one: that of life. Whether he was in some remote four corner of the world, charged by an elephant (he was almost killed in 1996), being a party animal in New York, or serene and rested in his house in Montauk, he immortalized the life he observes, excitement and wildness, happiness and injustice.

“Without memory, there is no life,†said Lee Radziwill in her aged, smoky voice. In 1972, the troop of friends had gone out to scout to film Big and Little Edie Bouvier Beale, respectively aunt and cousin of Lee and Jackie, American socialites, singer and dancer gently crossed out.

In their large, almost ruin of a house in the Hamptons, where they lived surrounded by cats, the gang of friends gathered for the summer running after lost time and listening to the eccentric stories of the amazing life of the two women. Stories from a bygone era, from the glorious Hamptons to the grand mansions where one was entertained and from a New York of glitter and madness, which foreshadowed the classic of the American documentary: Gray Gardens (1975).

A stroll through an era forgotten by a band of young and carefree troublemakers, in the same way that generations of lovers will stroll for a long time, together, in the pictures of Peter Beard in search of a bygone era.

Original in French here.

26 Apr 2020

I was reading the latest American Rifleman and came upon, forsooth! an entire article on the advanced and technical subject of putting your pistol back in its holster safely.

Representative of the earlier America that I am, my chin dropped, my eyes blinked, my mind boggled. I thought back to the Field & Stream magazines of my youth, and exercise my imagination as I might, I simply could not imagine H.G. Tapply, Ted Trueblood, or gun editor Warren Page feeling it useful or appropriate to undertake to instruct readers on just how to insert a gun into a holster.

But, as I sat there, reflecting mournfully on der Untergang des Abendlandes, it occurred to me that there actually is a justification for such an article, and that justification is The Glock.

Glock Leg is an actual well-known term that has made dictionaries of slang and popular phrase.

My own opinion is that there are a lot of idiots these days publishing opinions on guns and self defense who have accepted the highly dubious proposition that a semiautomatic pistol with a long trigger pull is really the same thing as a revolver and does not need a safety. These dingbats also commonly assert there is this profound hazard that, in the heat of the moment, in a situation where the shooter is under pressure, he is liable to forget to flick off the safety with his thumb when the need arises to fire.

I’d say they are nuts. Are any of these guys hunters? I’ve hunted grouse and other small game since I was in the last years of elementary school, and I have never in my life had any problem moving the shotgun safety with my thumb before pulling the trigger. And I will contend happily that when Old Ruff explodes unexpectedly from under your feet or from directly behind you, you are often startled, surprised, and trying to cope with the situation with all possible haste. An encounter with human adversaries is far more likely to take place over an interval of time providing plenty of opportunity to plan ahead, make ready, and even to contemplate one’s options.

It’s not easy to explain exactly why, but I do think revolvers and semiautomatic pistols are fundamentally different. I have no yearning for a safety on my revolver, like some of the strange continental European handguns sometimes had. But the very idea of carrying around an automatic pistol with no safety and round in the chamber just gives me the heebie jeebies. It strikes me as equivalent to climbing over a fence while hunting, carrying a loaded shotgun with the safety off.

If it were up to me, gun makers trying to sell Glocks and all the other safety-less polymer guns (and, yes, in my book, a trigger safety is the same as no safety) would be going out of business due to a lack of sales.

I once fired a Glock, when I had to take a Gun Safety Course (despite being a gun owner and hunter for decades and decades) in order to get a CT gun permit. I found the Glock easy to shoot accurately. They are good at soaking up recoil. But… Glocks are ugly. And a key reason they are so popular is that they are cheap. Gaston Glock was obviously clever in a number of ways, but he was also clearly coming from somewhere very far from the traditions, ergonomics, and habits of use of American gunners.

If there were no Glocks, nobody would need articles advising them on how not to shoot themselves on the leg putting their gun back in the holster.

As I get older, I find the list of fashionable things connected with guns that I detest gets longer and longer. One of these days, I intend to share my detestation of the Picatinny Rail.

25 Apr 2020

Andrew can’t take much more of this sitting around at home, reading books, and binge-watching Battlestar Gallactica. It’s all just too stressful for the poor chap.

This Friday’s column begins:

I began to lose it this week.

I know, I have it very easy. I’m not required to put myself at risk every day as a hospital or essential worker. I’m still employed. I’ve got some savings, and don’t have to worry about basic survival. I get food delivered. I haven’t lost any family members or friends from COVID-19 (though I did lose my dad in a horrible accident, and couldn’t get to the burial). My apartment gets plenty of sun and I have two dogs who love me. I get a couple of good walks in a day, and have plenty to read. I don’t have kids. I have direct, personal experience of living through a plague once before in my life.

All of that should make me a prime candidate to hang in, take this period as a disciplinary exercise, and generally be a good citizen. And I have been — I haven’t had any physical human contact for two months now, I wear a mask everywhere, I use rubber disposable gloves for groceries, I keep my six-feet distance so far as I can, even though it’s impossible in my neighborhood to walk on a sidewalk or in a park and not be accosted by joggers, who routinely come within inches of my face. I have no intention of breaking any of these rules, although I am tempted by homicide if any of these fit, entitled motherfuckers actually spit on the ground near me.

But I can recognize signs of psychological and physical stress, and I’m beginning to lose it. This week, for some reason, Wednesday was a bad day. Or at least I think it was Wednesday. What day is it again?

My sleep patterns are totally screwed up, and I find myself waking up tense several times a night, or crashing out for 10 or 12 hours at a time. I wake up and want to go back to sleep. My appetite is waning, and my body longs for some weights to push and pull. My teeth grind all night long and my jaw is tense. I have all the time in the world to read and write, and yet I find myself anesthetized with ennui, procrastinating and distracting myself. Yes, I scan the news every day, often hourly, to discern any seeds of progress.

And here’s the thing: I can’t see much on the horizon.

On the whole, I think it’s just as well that Andrew missed the plague in London in Pepys’ time, Waterloo, WWI, and the Blitz.

/div>

Feeds

|