Archive for April, 2020

15 Apr 2020

Andrew A. Michta contends that the principles of Liberalism and Free Trade are philosophically fine, but have unacceptable drawbacks in a real world in which your trading partner is also your adversary and has no respect for human life.

By striving to “flatten†the world (in Thomas Friedman’s memorable phrase) into a single, borderless entity in pursuit of nothing but profit and prosperity, this worldview has created huge blind spots. For example, it was powerless to predict that China would build on its early advantage in sheer numbers of low-skilled workers to lock in a dominant and increasingly powerful position for itself in global supply chains. Economies of scale played their part, as did the complementarity of the various manufacturing sectors the country strategically developed, not to mention China’s bullying and corrupting practices. The end result was that the costs of shifting to poorer countries would be unappetizing to corporate supply chain managers. Worse still, such thinking could not account for the fact that behind the scores of successful companies lay a monolithic, totalitarian, nationalist entity with a vision for restoring China’s role in the world: the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

When bereft of redundancies, networks devolve to hierarchies, which in turn create winners and losers. Hierarchies do not diminish the key importance of state power in international relations. On the contrary, they enable it. As China has grown to become the seemingly irreplaceable core of a globalized economy, the CCP has pursued predatory mercantilism in its commercial relations with the West, in the process tilting the hard power balance in its favor. In an economic system that allows for the flow of technology and capital across national borders, redundancies in the supply chain are essential to the preservation of state sovereignty and government capacity to act in a crisis. The Wuhan Virus pandemic is proving so devastating because the radical centralization of market networks has allowed for failure at a single point in our supply chain to leave the system with no capacity to off-load demand onto redundant networks.

In short, globalization, as preached and practiced over the past four decades, has been shown for what it has always been: profiteering off of a vast pool of centrally controlled labor. While many vast fortunes have been made in the West as a result, and as American consumers binged on low-cost goods, the biggest winner has naturally been the Chinese Communist Party elite. And though even before the 2016 U.S. election there was a growing realization among Western captains of industry that something was not quite right with China’s role in the system, few were willing to ask big enough questions about the system as a whole.

The fundamental question is one of values: Is this kind of globalization compatible with liberty and democratic governance? My simple answer is no. By ignoring the role of nations in the international system—or, if not ignoring, indeed prophesying the nation’s demise—globalization’s boosters have implicitly, if perhaps unwittingly, lessened the accountability of elites and downgraded the voice of voters in these matters. No citizenry, if asked, would vote for the status quo—their working-class communities gutted, their security endangered, and their country made dependent on an adversarial foreign power.

RTWT

In the end, cheaper running shoes and smart phones are just not worth it.

15 Apr 2020

Detail, Pieter Brueghel the elder, Parable of the Blind Men, Museo e Gallerie Nazionali di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy, 1568.

Victor Davis Hanson observes that credentialed experts’ supposed omniscience has been reduced to tatters by the recent COVID-19 wordwide outbreak.

The virus will teach us many things, but one lesson has already been relearned by the American people: there are two, quite different, types of wisdom.

One, and the most renowned, is a specialization in education that results in titled degrees and presumed authority. That ensuing prestige, in turn, dictates the decisions of most politicians, the media, and public officials—who for the most part share the values and confidence of the credentialed elite.

The other wisdom is not, as commonly caricatured, know-nothingism. Indeed, Americans have always believed in self-improvement and the advantages of higher education, a trust that explained broad public 19th-century support for mandatory elementary and secondary schooling and, during the postwar era, the G.I. Bill.

But the other wisdom also puts a much higher premium on pragmatism and experience, values instilled by fighting nature daily and mixing it up with those who must master the physical world.

The result is the sort of humility that arises when daily drivers test their skills and cunning in a semi-truck barreling along the freeway to make a delivery deadline with a cylinder misfiring up on the high pass, while plagued by worries whether there will be enough deliveries this month to pay the mortgage.

An appreciation of practical knowledge accrues from watching central-heating mechanics come out in the evening to troubleshoot the unit on the roof, battling the roof grade, the ice, and the dark while pitting their own acquired knowledge in a war with the latest computerized wiring board of the new heating exchange unit that proves far more unreliable than the 20-year-old model it replaced.

Humility is key to learning, but it is found more easily from a wealth of diverse existential experiences on the margins. It is less a dividend of the struggle for great success versus greater success still, but one of survival versus utter failure.

So far in this crisis, our elite have let us down in a manner the muscularly wise have never done.

RTWT

14 Apr 2020

Rue Quincampoix is a one-bedroom, two-bathroom home in Le Marais. On the sitting room’s mezzanine, you’ll find another sumptuous bed, making the office the comfortable quarters for a third guest. Every room in this opulent 17th-century home has been furnished with a wealth of museum-worthy antiques and artworks carefully chosen by its discerning designers. From the sitting room’s original fireplace and Italian Renaissance paintings to the contemporary Shen Wei piece that hangs above the master bed, you’ll discover many unique treasures here. Even the bathrooms are an Ottoman-inspired dream. Rue Quincampoix is beautifully situated too – on one of the oldest streets in Paris, close to all the city’s sights and just a two-minute walk from Rambuteau metro station.

For rent at only $675 a night. Here.

14 Apr 2020

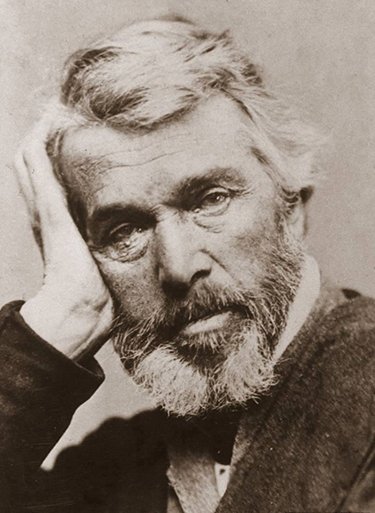

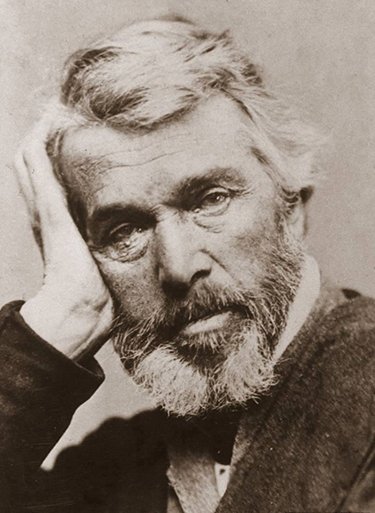

Either Thomas Carlyle or Curtis Yarvon, hard to tell.

Jonathan Radclyffe discusses the latest instantiations of Moldbugism in the same delightfully learned, amusingly provocative, and ungodly prolix manner of the original, prose as dense and ultimately indigestible as a Christmas fruitcake.

Still, I do not believe that I have ever read a better précis of Moldbugian Neo-Reactionism.

Recently something rather unexpected happened. Curtis Yarvin began writing again. A decade ago, back in the spotty youth of the internet when blogs meant something, Yarvin, a Silicon Valley computer programmer, made a cult name for himself under the nom de plume of reactionary political philosopher Mencius Moldbug. Often memed, frequently cited as an important ancestor of the “alt-right†(but largely left unread) and father of the online political movement known as NRx/neo-reaction (which has been declared dead endlessly since at least 2013), Moldbug may well be the only notable political philosopher wholly created by and disseminated through the internet.

In his journey from Austrian Economics to attempting to update early modern absolute monarchy for the information age, Yarvin regularly churned out tens of thousands of word screeds on his blog Unqualified Reservations (UR) about the need to privatise the state and hand it over to an efficient CEO monarch to keep progressives out, the Christian roots of progressivism, and encomia to nineteenth century Romantic Thomas Carlyle. All of this was so liberally coated in rhetorical irony and Carlylean bombast that it was often difficult to tell what was supposed to be serious and what was not. Moldbug was among the first to discover the power of reactionary post-irony, though these days of course, playing long-read rhetorical games to affect ideological change seems a rather primitive affair. The work of post-irony can now be compressed into a couple of memes very easily.

Between 2007 and 2010 Moldbug was immensely prolific. Thereafter UR petered off as Yarvin turned his efforts increasingly towards developing a blockchain-based data-storage scheme called Urbit.[1] By 2014, when Moldbug began to become a household name across the internet as the social media platforms were increasingly politicised, Moldbug was pretty much finished writing. In April 2016 UR was wrapped up with a “Coda†declaring that it had “fulfilled its purpose.†The same month attendees threatened to withdraw from the LambdaConf computing conference because the “proslavery†Yarvin would be speaking at it (Towsend 2016).[2] To this Yarvin (2016a) wrote a reply insisting on the innocence of his Moldbuggian stage as simply a matter of curiosity about ideology. The same year in an open Q&A session about Urbit on Reddit, Yarvin (2016b) was more than happy to answer some questions about Moldbug and defend both projects as parts of a dual mission to democratise the current monopolies controlling the internet and to dedemocratise politics for the sake of enlightened monopoly.

In early 2017, following Trump’s election, rumours began to circulate that Yarvin was in communication with Steve Bannon, though nothing came of this (Matthews 2017b). Around the same time Yarvin was quoted as supporting single-payer healthcare (Matthews 2017a). News also surfaced that Yarvin was on a list of people to be thrown off Google’s premises, should he ever make a visit (Atavisionary 2018). Then, early in 2019, Yarvin (2019a) quit Urbit after seventeen years on the project, causing some to wonder whether Moldbug might now make a return. Old rumours also began to get about the place that Yarvin was behind Nietzschean Twitter reactionary Bronze Age Pervert (BAP), especially after Yarvin passed a copy of BAP’s book Bronze Age Mindset to Trumpist intellectual Michael Anton (2019) with the insistence that this was what “the kids†are into these days. And now Yarvin has started publishing again, under his own name, a decade on from the salad days of UR. On the 27th of September 2019 the first of a five-part essay for the conservative Claremont Institute’s The American Mind landed, titled “The Clear Pill.â€

If Moldbug/Yarvin is famous for one thing, it is that he’s the fellow who put the symbol of the “red pill†into reactionary discourse. The “Clear Pill†promises to be a reset of ideology in which progressivism, constitutionalism and fascism will each receive an “intervention†through their own language and values to show up how “ineffectual†each is (Yarvin 2019b). Thus far this “clear pill†sounds all rather typically Moldbuggian–for Yarvin it has always been about resetting the state and the rhetoric of undoing brainwashing. Anyone passingly familiar with the oeuvre of Moldbug knows that Yarvin is more than capable of speaking all three of these political dialects reasonably well, even if, as Elizabeth Sandifer (2017) astutely notes, Moldbug is so deep in neoliberal TINA [DZ: “TINA” is slang for crystal meth.] he is unable to take Marxism seriously as a contemporary opponent at all. For Moldbug the American liberal pursuit of equality was always more “communist†than the USSR, which is to say, paranoid reactionary hyperbole aside, that he only ever regarded Marxism as an early phase of progressivism.

And yet, six months on from the first part of the “Clear Pillâ€, only a second of the promised five parts has thus far been published. Part two (Yarvin 2019c), or “A Theory of Pervasive Error†appeared on the 25th of November, and, so one might surmise, even the most die-hard Moldbug-fans must have found it somewhat lacking. The initial purpose of the piece seems to be to outline a theory of human desire that utilises the Platonic language of thymos (courageous spirit), but ends up sounding far closer to a Neo-Darwinian Hobbes than anything else. Human beings are petty and selfish beasts, we are encouraged to believe. The essay meanders on until it finally arrives at the simple old Moldbuggian point that because liberal “experts†in governance and science have a touted monopoly on truth, they should not automatically be trusted. That’s it. By taking such the long way around to say something so simple and banal, the result is more than a little anticlimactic. Perhaps after all these years the bounce has gone out of Yarvin’s bungy; his lemonade has gone flat.

The only other piece to appear on The American Mind from Yarvin since “A Theory of Pervasive Error†has not been part of this “Clear Pill†series, but a stand-alone essay published on the 1st of February 2020 titled “The Missionary Virusâ€. In this Yarvin argues that the recent coronavirus pandemic offers an unparallel opportunity to dismantle American “internationalism†and reboot a politically and culturally multi-polar world while economic globalisation continues. Imagine, Yarvin asks the reader, what it would be like if the virus did not go away and the travel bans lasted not a month, but a decade, or centuries. One thing can be said about this essay that cannot be said of the “Clear Pill†so far – at very least it is entertaining. Perhaps parts three to five of the “Clear Pill†will actually say something interesting after all.

Indeed there are all sorts of questions that are still left unanswered. Will the crescendo of part five simply restate the need to privatise governance and let the market system work? Will Yarvin take some drastic new turn or even disown Moldbug? Will he finally acknowledge eccentric death-cultist Nick Land, who, for the best part of this decade has largely been the “king†of NRx as a political ideology? We must wait and see.

It goes on… and on… and on.

TWT

13 Apr 2020

Did girls actually gun down mashers back in the 1950s? I don’t seem to remember hearing about it, but here’s Colt marketing its light-weight 2″-barrel .38 Special Cobra revolver as the maiden’s answer to unwanted male attention.

13 Apr 2020

M. Brandon Godbey identifies what Americans ought to learn from the COVID-19 national freakout.

1) Incompetent bureaucracy: The CDC and FDA played hot potato with the COVID Crisis for months without any coherent strategy. It seems like the more government agencies become involved in the process the more muddled our future becomes. We have found that the medical bureaucracy, like all bureaucracies, eventually falls victim to entropy. At some unknown point in the last 20 years, it stopped functioning as a legitimate source of medical leadership. Today, it is a mass of purposeless tentacles that primarily exists for the sake of self-perpetuation.

2) The Corruption of “Experts“: Since the way to big money in the sciences is through government grants, the way you “hit it big†in science isn’t by finding empirical truth, it’s by repeating opinions that politicians want to hear. We have thus created a generation of quasi-scientists that feed off the government teat with the tenacity of even the worst parasites. When stressed by the pandemic, this system quickly devolved into competing scientific factions, each one pitching their own version of a doomsday scenario for the sake of money, prestige, and sheer professional vanity.

3) Feckless Politicians: Instead of leading in a time of crisis, governors and mayors are taking the path that absolves them from guilt instead what is best for citizens. Constantly in reelection mode, they make choices based on what they might be blamed for instead of what is right. When decisions are made through the “reelect me at all cost†framework, civil right quickly go out the window. Last night, my own governor reassured the Commonwealth of Kentucky that he was perfectly willing to use Gestapo tactics to record the licence plate numbers of those that attend Easter services and effectively put them under house arrest. Other governors have behaved in a similar manner, each one trying to one-up their neighbor.

4) Our Decadent Society: We have become a tragically unserious people, obsessed with celebrity and sorely lacking in critical thinking skills. Social media algorithms have spoon-fed us our own views over and over again. Mass media feeds our inherent cognitive biases, facilitating a surreal kind of mass paralysis that consists of one part hysteria and one part blind submission. We have become the grotesque inhabitants of the mindless hive from E.M. Forester’s imagination. The lessons of history lost on us, we behave like sheep walking to the slaughter, bleating in unison.

5) We are Coddled and Soft: Our lives are easy, and many of us have become detached from the world of hard-working men and women that make our lives possible. We want the truckers to deliver our food and the servers to bring it to us, but we gleefully clap when the economy that supports them is torn asunder. Our general lack of understanding of the collaborative nature of macroeconomics is appalling. Products arrive at our doorstep; food appears in front of us; entertainment is provided in multiple forms at any time or place. Yet the processes by which these miracles are created are so remote and alien to us that we are perfectly willing to watch them burn to satisfy our busybody natures.

RTWT

13 Apr 2020

Certainly not the most beautiful, but a Corvette I’d never seen. They only made 3600 of them that year. Very nice for a Corvette.

I hate clickbait format sites like this one. But I will admit this one is almost worth all the trouble and delays of wading through page after page, accidentally hitting an ad link ever now and then.

Obviously not all the most beautiful cars ever made. (How in hell did that Citroen get in there?) Far too short of pre-WWII cars, needs a lot more British cars and more of the very old Alfas. You could make Bugattis half the list. But, still, worth a look.

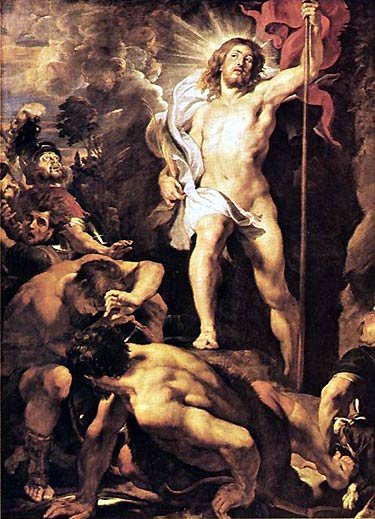

12 Apr 2020

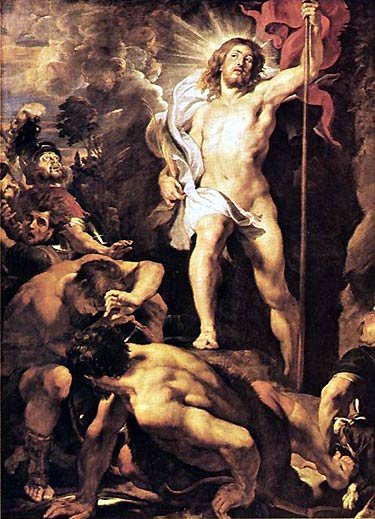

Peter Paul Rubens, The Resurrection of Christ, 1611-1612, Vrouwekathedraal, Antwerp

From Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, 1869:

Easter

Easter, the anniversary of our Lord’s resurrection from the dead, is one of the three great festivals of the Christian year,—the other two being Christmas and Whitsuntide. From the earliest period of Christianity down to the present day, it has always been celebrated by believers with the greatest joy, and accounted the Queen of Festivals. In primitive times it was usual for Christians to salute each other on the morning of this day by exclaiming, ‘Christ is risen;’ to which the person saluted replied, ‘Christ is risen indeed,’ or else, ‘And hath appeared unto Simon;’—a custom still retained in the Greek Church.

The common name of this festival in the East was the Paschal Feast, because kept at the same time as the Pascha, or Jewish passover, and in some measure succeeding to it. In the sixth of the Ancyran Canons it is called the Great Day. Our own name Easter is derived, as some suppose, from Eostre, the name of a Saxon deity, whose feast was celebrated every year in the spring, about the same time as the Christian festival—the name being retained when the character of the feast was changed; or, as others suppose, from Oster, which signifies rising. If the latter supposition be correct, Easter is in name, as well as reality, the feast of the resurrection.

Though there has never been any difference of opinion in the Christian church as to why Easter is kept, there has been a good deal as to when it ought to be kept. It is one of the moveable feasts; that is, it is not fixed to one particular day—like Christmas Day, e. g., which is always kept on the 25th of December—but moves backwards or forwards according as the full moon next after the vernal equinox falls nearer or further from the equinox. The rule given at the beginning of the Prayer-book to find Easter is this: ‘Easter-day is always the first Sunday after the full moon which happens upon or next after the twenty-first day of March; and if the full moon happens upon a Sunday, Easter-day is the Sunday after.’

The paschal controversy, which for a time divided Christendom, grew out of a diversity of custom. The churches of Asia Minor, among whom were many Judaizing Christians, kept their paschal feast on the same day as the Jews kept their passover; i. e., on the 14th of Nisan, the Jewish month corresponding to our March or April. But the churches of the West, remembering that our Lord’s resurrection took place on the Sunday, kept their festival on the Sunday following the 14th of Nisan. By this means they hoped not only to commemorate the resurrection on the day on which it actually occurred, but also to distinguish themselves more effectually from the Jews. For a time this difference was borne with mutual forbearance and charity. And when disputes began to arise, we find that Polycarp, the venerable bishop of Smyrna, when on a visit to Rome, took the opportunity of conferring with Anicetas, bishop of that city, upon the question. Polycarp pleaded the practice of St. Philip and St. John, with the latter of whom he had lived, conversed, and joined in its celebration; while Anicetas adduced the practice of St. Peter and St. Paul. Concession came from neither side, and so the matter dropped; but the two bishops continued in Christian friendship and concord. This was about A.D. 158.

Towards the end of the century, however, Victor, bishop of Rome, resolved on compelling the Eastern churches to conform to the Western practice, and wrote an imperious letter to the prelates of Asia, commanding them to keep the festival of Easter at the time observed by the Western churches. They very naturally resented such an interference, and declared their resolution to keep Easter at the time they had been accustomed to do. The dispute hence-forward gathered strength, and was the source of much bitterness during the next century. The East was divided from the West, and all who, after the example of the Asiatics, kept Easter-day on the 14th, whether that day were Sunday or not, were styled Qiccertodecimans by those who adopted the Roman custom.

One cause of this strife was the imperfection of the Jewish calendar. The ordinary year of the Jews consisted of 12 lunar months of 292 days each, or of 29 and 30 days alternately; that is, of 354 days. To make up the 11 days’ deficiency, they intercalated a thirteenth month of 30 days every third year. But even then they would be in advance of the true time without other intercalations; so that they often kept their passover before the vernal equinox. But the Western Christians considered the vernal equinox the commencement of the natural year, and objected to a mode of reckoning which might sometimes cause them to hold their paschal feast twice in one year and omit it altogether the next. To obviate this, the fifth of the apostolic canons decreed that, ’ If any bishop, priest, or deacon, celebrated the Holy Feast of Easter before the vernal equinox, as the Jews do, let him be deposed.’

At the beginning of the fourth century, matters had gone to such a length, that the Emperor Constantine thought it his duty to take steps to allay the controversy, and to insure uniformity of practice for the future. For this purpose, he got a canon passed in the great Ecumenical Council of Nice (A.D. 325), that everywhere the great feast of Easter should be observed upon one and the same day; and that not the day of the Jewish passover, but, as had been generally observed, upon the Sunday afterwards. And to prevent all future disputes as to the time, the following rules were also laid down:

‘That the twenty-first day of March shall be accounted the vernal equinox.’

‘That the full moon happening upon or next after the twenty-first of March, shall be taken for the full moon of Nisan.’

‘That the Lord’s-day next following that full moon be Easter-day.’

‘But if the full moon happen upon a Sunday, Easter-day shall be the Sunday after.’

As the Egyptians at that time excelled in astronomy, the Bishop of Alexandria was appointed to give notice of Easter-day to the Pope and other patriarchs. But it was evident that this arrangement could not last long; it was too inconvenient and liable to interruptions. The fathers of the next age began, therefore, to adopt the golden numbers of the Metonic cycle, and to place them in the calendar against those days in each month on which the new moons should fall during that year of the cycle. The Metonie cycle was a period of nineteen years. It had been observed by Meton, an Athenian philosopher, that the moon returns to have her changes on the same month and day of the month in the solar year after a lapse of nineteen years, and so, as it were, to run in a circle. He published his discovery at the Olympic Games, B.C. 433, and the cycle has ever since borne his name. The fathers hoped by this cycle to be able always to know the moon’s age; and as the vernal equinox was now fixed to the 21st of March, to find Easter for ever. But though the new moon really happened on the same day of the year after a space of nineteen years as it did before, it fell an hour earlier on that day, which, in the course of time, created a serious error in their calculations.

A cycle was then framed at Rome for 84 years, and generally received by the Western church, for it was then thought that in this space of time the moon’s changes would return not only to the same day of the month, but of the week also. Wheatley tells us that, ‘During the time that Easter was kept according to this cycle, Britain was separated from the Roman empire, and the British churches for some time after that separation continued to keep Easter according to this table of 84 years. But soon after that separation, the Church of Rome and several others discovered great deficiencies in this account, and therefore left it for another which was more perfect.’—Book on the Common Prayer, p. 40. This was the Victorian period of 532 years. But he is clearly in error here. The Victorian period was only drawn up about the year 457, and was not adopted by the Church till the Fourth Council of Orleans, A.D. 541.

Now from the time the Romans finally left Britain (A.D. 426), when he supposes both churches to be using the cycle of 84 years, till the arrival of St. Augustine (A.D. 596), the error can hardly have amounted to a difference worth disputing about. And yet the time the Britons kept Easter must have varied considerably from that of the Roman missionaries to have given rise to the statement that they were Quartodecimans, which they certainly were not; for it is a well-known fact that British bishops were at the Council of Nice, and doubtless adopted and brought home with them the rule laid down by that assembly. Dr. Hooke’s account is far more probable, that the British and Irish churches adhered to the Alexandrian rule, according to which the Easter festival could not begin before the 8th of March; while according to the rule adopted at Rome and generally in the West, it began as early as the fifth. ‘They (the Celts) were manifestly in error,’ he says; ‘but owing to the haughtiness with which the Italians had demanded an alteration in their calendar, they doggedly determined not to change.’—Lives of the Archbishops of Canterbury, vol. i. p. 14.

After a good deal of disputation had taken place, with more in prospect, Oswy, King of Northumbria, determined to take the matter in hand. He summoned the leaders of the contending parties to a conference at Whitby, A.D. 664, at which he himself presided. Colman, bishop of Lindisfarne, represented the British church. The Romish party were headed by Agilbert, bishop of Dorchester, and Wilfrid, a young Saxon. Wilfrid was spokesman. The arguments were characteristic of the age; but the manner in which the king decided irresistibly provokes a smile, and makes one doubt whether he were in jest or earnest. Colman spoke first, and urged that the custom of the Celtic church ought not to be changed, because it had been inherited from their forefathers, men beloved of God, &c. Wilfrid followed:

‘The Easter which we observe I saw celebrated by all at Rome: there, where the blessed apostles, Peter and Paul, lived, taught, suffered, and were buried.’ And concluded a really powerful speech with these words: ‘And if, after all, that Columba of yours were, which I will not deny, a holy man, gifted with the power of working miracles, is he, I ask, to be preferred before the most blessed Prince of the Apostles, to whom our Lord said, “Thou art Peter, and upon this rock will I build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it; and to thee will I give the keys of the kingdom of heaven†?’

The King, turning to Colman, asked him, ‘Is it true or not, Colman, that these words were spoken to Peter by our Lord?’ Colman, who seems to have been completely cowed, could not deny it. ‘It is true, 0 King.’ ‘Then,’ said the King, ‘can you shew me any such power given to your Columba? ’ Colman answered, ’ No.’ ‘You are both, then, agreed,’ continued the King, are you not, that these words were addressed principally to Peter, and that to him were given the keys of heaven by our Lord?’ Both assented. ‘Then,’ said the King, ‘I tell you plainly, I shall not stand opposed to the door-keeper of the kingdom of heaven; I desire, as far as in me lies, to adhere to his precepts and obey his commands, lest by offending him who keepeth the keys, I should, when I present myself at the gate, find no one to open to me.’

This settled the controversy, though poor honest Colman resigned his see rather than submit to such a decision.

On Easter-day depend all the moveable feasts and fasts throughout the year. The nine Sundays before, and the eight following after, are all dependent upon it, and form, as it were, a body-guard to this Queen of Festivals. The nine preceding are the six Sundays in Lent, Quinquagesima, Sexagesima, and Septuagesima; the eight following are the five Sundays after Easter, the Sunday after Ascension Day, Whit Sunday, and Trinity Sunday.

EASTER CUSTOMS

The old Easter customs which still linger among us vary considerably in form in different parts of the kingdom. The custom of distributing the ‘pace’ or ‘pasche ege,’ which was once almost universal among Christians, is still observed by children, and by the peasantry in Lancashire. Even in Scotland, where the great festivals have for centuries been suppressed, the young people still get their hard-boiled dyed eggs, which they roll about, or throw, and finally eat. In Lancashire, and in Cheshire, Staffordshire, and Warwickshire, and perhaps in other counties, the ridiculous custom of ‘lifting’ or ‘heaving’ is practised.

On Easter Monday the men lift the women, and on Easter Tuesday the women lift or heave the men. The process is performed by two lusty men or women joining their hands across each other’s wrists; then, making the person to be heaved sit down on their arms, they lift him up aloft two or three times, and often carry him several yards along a street. A grave clergyman who happened to be passing through a town in Lancashire on an Easter Tuesday, and having to stay an hour or two at an inn, was astonished by three or four lusty women rushing into his room, exclaiming they had come ‘to lift him.’ ‘To lift me!’ repeated the amazed divine; ‘what can you mean?’ ‘Why, your reverence, we’re come to lift you, ‘cause it’s Easter Tuesday.’ ‘Lift me because it’s Easter Tuesday? I don’t understand. Is there any such custom here?’ ‘Yes, to be sure; why, don’t you know? all us women was lifted yesterday; and us lifts the men today in turn. And in course it’s our rights and duties to lift ‘em.’

After a little further parley, the reverend traveller compromised with his fair visitors for half-a-crown, and thus escaped the dreaded compliment. In Durham, on Easter Monday, the men claim the privilege to take off the women’s shoes, and the next day the women retaliate. Anciently, both ecclesiastics and laics used to play at ball in the churches for tansy-cakes on Eastertide; and, though the profane part of this custom is happily everywhere discontinued, tansy-cakes and tansy-puddings are still favourite dishes at Easter in many parts. In some parishes in the counties of Dorset and Devon, the clerk carries round to every house a few white cakes as an Easter offering; these cakes, which are about the eighth of an inch thick, and of two sizes —the larger being seven or eight inches, the smaller about five in diameter— have a mingled bitter and sweet taste. In return for these cakes, which are always distributed after Divine service on Good Friday, the clerk receives a gratuity- according to the circumstances or generosity of the householder.

11 Apr 2020

A picture recently taken of brave wizard warriors attempting to bind this demon to an astral entrapment on the floor.

HT: Mike Moroski via Karen L. Myers.

11 Apr 2020

Smithsonian:

A nine-year study of cougars in the Yellowstone National Park has found that nearly half of the big cats they tracked were infected with the plague-carrying bacteria Yersinia pestis at some point, according to a paper published last month in Environmental Conservation.

The Y. pestis bacteria is behind the Black Death, the mid-1300s epidemic of bubonic plague that in five years killed over 20 million people in Europe. These days, only about seven people catch Y. pestis each year in the United States. The bacteria lives in the soil, gets picked up by fleas living on rodents, and infects other creatures on its way up the food chain. The new evidence in cougars, also known as pumas and mountain lions, shows how flexible and dangerous the pathogen is in different hosts.

The study was conducted on cougars in the southern Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, specifically in Jackson Hole, the valley east of the Grand Teton mountain range and south of Yellowstone National Park. “You start to get a clear picture of how hard it is to be a mountain lion in Jackson Hole,†biologist and co-author Howard Quiqley tells Mike Koshmrl of Wyoming News. “If you get to be an adult mountain lion in Jackson Hole, you’re a survivor.â€

RTWT

I guess it’s not really surprising. Black Plague is known to be endemic to rodent populations pretty much all over The West.

/div>

Feeds

|