Category Archive 'Antiquities'

15 Aug 2016

Portonaccio Sarcophagus, 2nd Century A.D., Museo Nazionale Romano

Kuriositas profiles an exceptionally spectacular ancient sculpture featuring particularly realistic and fine battle scenes:

It was discovered in 1931 near Via Tiburtina, in the eastern suburbs of Rome. Its front depicts a symbolic picture of a battle which is on two levels. The carving remains to this day an incredible achievement – the dark and light contrast beautifully to produce a veritable chiaroscuro effect. This skill involved was superlative.

The sarcophagus was probably used in the burial of a Roman general who was closely involved in the campaigns of Marcus Aurelius. He is seen on the front of the sarcophagus, frozen forever in a charge against his enemies. Yet the face of the high ranking officer for which the sarcophagus was intended is left blank.

It is thought that it was left blank with the intention of the sculptor creating a death mask of the general in that position. Yet perplexingly it has been left unfinished and we can only guess at the reasons for that. We will never know if some form of shame descended on the general before his death or why it was his family or friends decided that he was to be left nameless and faceless for eternity.

Certainly it was not for expediency or money. This sarcophagus would have been incredibly expensive to create and would probably have taken over a year to create. Plus the rest of it (and thus his reputation) was left intact. You can see his troops laying in to their barbarian enemies with gusto. Some are already on the ground, others apparently beg for his mercy. …

The military insignia which can be seen on the upper edge of the casket allows us to try to figure out the identity of the man. It shows the eagle of the Legio IIII Flavia and the boar of the Legio I Italicai. Historians who have studied the casket have pointed towards Aulus Iulius Pompilius. He was an official of Marcus Aurelius who was in control of two squadrons of cavalry which were on detachment to both legions for the duration of the war against the Marcomanni (172-175AD).

Portonaccio Sarcophagus, 2nd Century A.D., Museo Nazionale Romano

05 Jul 2016

The Ribchester Helmet is a Roman bronze ceremonial helmet dating to between the late 1st and early 2nd centuries AD, … now on display at the British Museum. It was found in Ribchester, Lancashire, England in 1796, as part of the Ribchester Hoard. The model of a sphinx that was believed to attach to the helmet was lost.

Wikipedia:

The helmet was discovered, part of the Ribchester Hoard, in the summer of 1796 by the son of Joseph Walton, a clogmaker. The boy found the items buried in a hollow, about three metres below the surface, on some waste land by the side of a road leading to Ribchester church, and near a river bed. The hoard was thought to have been stored in a wooden box and consisted of the corroded remains of a number of items but the largest was this helmet. In addition to the helmet, the hoard included a number of paterae, pieces of a vase, a bust of Minerva, fragments of two basins, several plates, and some other items that the antiquarian collector Charles Townley thought had religious uses. The finds were thought to have survived so well because they were covered in sand.

The helmet and other items were bought from Walton by Townley, who lived nearby at Towneley Hall. Townley was a well-known collector of Roman sculpture and antiquities, who had himself and his collection recorded in an oil painting by Johann Zoffany. Townley reported the details of the find in a detailed letter to the secretary of the Society of Antiquaries, intended for publication in the Society’s Proceedings: it was his only publication. The helmet, together with the rest of Townley’s collection, was sold to the British Museum in 1814 by his cousin, Peregrine Edward Towneley, who had inherited the collection on Townley’s death in 1805.

In addition to the items purchased by Townley, there was also originally a bronze figurine of a sphinx, but it was lost after Walton gave it to the children of one of his brothers to play with. It was suggested by Thomas Dunham Whitaker, who examined the hoard soon after it had been discovered, that the sphinx would have been attached to the top of the helmet, as it has a curved base fitting the curvature of the helmet, and has traces of solder on it. This theory has become more plausible with the discovery of the Crosby Garrett Helmet in 2010, to which is attached a winged griffin.

21 Nov 2015

A Greek Late Archaic- maybe Etruscan – Bronze male siren.

Who knew that there were male sirens?

via Belacqui.

03 Jun 2015

A ROMAN GOLD AND GARNET WINGED THUNDERBOLT PENDANT

CIRCA 1ST CENTURY A.D.

From Christie’s.

26 Feb 2015

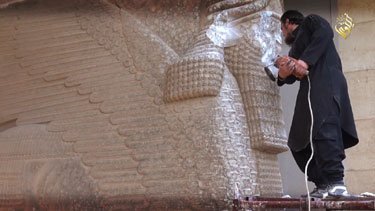

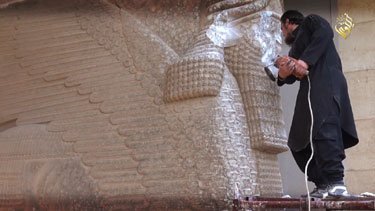

Conflict Antiquities has numerous images, demonstrating one more reason why the civilized world should not tolerate the activities or the existence of this insane regime.

30 Jan 2015

Ennion, mold-blown glass cups (1st century A.D)

From the Metropolitan Museum via Belacqui.

25 Apr 2014

c. 900-800 BCE: Unknown Artist: Lioness Devouring a Boy [Phoenician, Palace of Ashurnasirpal II, Nimrud, Iraq]

Ivory carving made by Phoenicians, found in the palace of the Assyrian king in Nimrud.

Wikipedia: Nimrud Ivories.

03 Oct 2013

Bronze flute. Egyptian, Ptolemaic period. Inscribed near the mouthpiece with: “The [divine] Nubian one and the gods of the resting place of the ibis to Thoteus son of Nekhtmonth.â€

35.9 cm length x 1.6 cm diameter.

(Source: British Museum)

Hat tip to Ratak Mondosico.

27 Aug 2013

Smithsonian magazine:

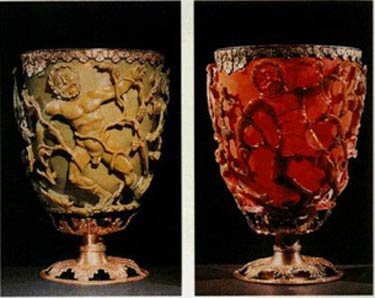

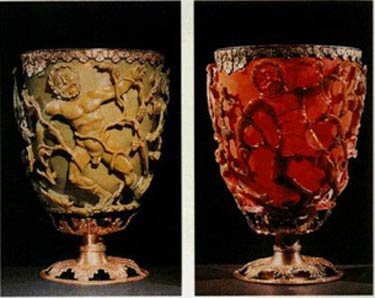

The colorful secret of a 1,600-year-old Roman chalice at the British Museum is the key to a superÂsensitive new technology that might help diagnose human disease or pinpoint biohazards at security checkpoints.

The glass chalice, known as the Lycurgus Cup because it bears a scene involving King Lycurgus of Thrace, appears jade green when lit from the front but blood-red when lit from behind—a property that puzzled scientists for decades after the museum acquired the cup in the 1950s. The mystery wasn’t solved until 1990, when researchers in England scrutinized broken fragments under a microscope and discovered that the Roman artisans were nanotechnology pioneers: They’d impregnated the glass with particles of silver and gold, ground down until they were as small as 50 nanometers in diameter, less than one-thousandth the size of a grain of table salt. The exact mixture of the precious metals suggests the Romans knew what they were doing—“an amazing feat,†says one of the researchers, archaeologist Ian Freestone of University College London.

The ancient nanotech works something like this: When hit with light, electrons belonging to the metal flecks vibrate in ways that alter the color depending on the observer’s position. Gang Logan Liu, an engineer at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who has long focused on using nanotechnology to diagnose disease, and his colleagues realized that this effect offered untapped potential. “The Romans knew how to make and use nanoparticles for beautiful art,†Liu says. “We wanted to see if this could have scientific applications.â€

When various fluids filled the cup, Liu suspected, they would change how the vibrating electrons in the glass interacted, and thus the color. (Today’s home pregnancy tests exploit a separate nano-based phenomenon to turn a white line pink.)

———————–

The cup’s history via Wikipedia:

The cup was “perhaps made in Alexandria” or Rome in about 290-325 AD, and measures 16.5 x 13.2 cm. From its excellent condition it is probable that, like several other luxury Roman objects, it has always been preserved above ground; most often such objects ended up in the relatively secure environment of a church treasury. Alternatively it might, like several other cage cups, have been recovered from a sarcophagus. The present gilt-bronze rim and foot were added in about 1800, suggesting it was one of the many objects taken from church treasuries during the period of the French Revolution and French Revolutionary Wars. The foot continues the theme of the cup with open-work vine leaves, and the rim has leaf forms that lengthen and shorten to match the scenes in glass. In 1958 the foot was removed by British Museum conservators, and not rejoined to the cup until 1973. There may well have been earlier mounts.

The early history of the cup is unknown, and it is first mentioned in print in 1845, when a French writer said he had seen it “some years ago, in the hands of M. Dubois”. This is probably shortly before it was acquired by the Rothschild family. Certainly Lionel de Rothschild owned it by 1862, when he lent it to an exhibition at what is now the V&A Museum, after which it virtually fell from scholarly view until 1950. In 1958 Victor, Lord Rothschild sold it to the British Museum for £20,000… .The cup is normally on display, lit from behind, in Room 50 (it forms part of the museum’s Department of Prehistory and Europe).

21 Aug 2013

Attributed to Agnes van den Bossche, The Maid of Ghent painted battle standard, circa 1481-1482.

The standard’s symbol of a maiden comes a 1388 poem by Bouden or Baudouin van der Loore, De maghet of Ghend (The Maiden of Ghent), a poem of 240-odd verses, which allegorically describes a war between the city of Ghent and Lodewijk van Maele, Count of Flanders fought between 1379 and 1385.

In a dream, the poet sees a beautiful arbor, located in the middle of a wilderness where two rivers come together: an allusion to the city of Ghent. In the arbor is seated a graceful lady, resplendent in black fur and wearing on her right arm fine gems spelling out the letters: G, H, E, N and D. The maiden is accompanied by a silver lion with golden crown and necklace — the defender of the city. In a clear voice, the maiden sings a heavenly song. But the maiden is soon threatened by a gang of soldiers who covet her purity and her freedom. Across the river appears the leader of the army who turns out to be none other than the father of the beleaguered virgin, i.e., the Count of Flanders. On his banner, he bears a black lion rampant on gold. The poet now warns the lady that they are surprised and surrounded by many enemies. She replies that she has ​​much good company which can come to the rescue if necessary. And when the poet looks around he sees emerging out of the mists from the North East, Christ, St. Jacob, St. Bavo, St. Macharius, and from the East came Saint George and Saint John, and from all directions, all the saints to whom were dedicated in Ghent churches from their exact geographical directions. With the protection of this heavenly host, the maiden has nothing to fear. Still, she hopes for a peaceful end to the conflict with her ​​father. The poet, now awakened, closes with a short prayer to God and the Virgin and all the saints to save the maiden and reconcile her with her ​​father.

Cool Chicks

STAM

17 Feb 2011

The Bookworm has some thoughts on the morality and practical consequences of returning antiquities from Western museums to their lands of origin.

The narrative has long been in place: For centuries, the predatory West raped the ancient world — Egypt, Greece, the Fertile Crescent, Persia — of her culture. Greedy treasure hunters and archeologists stole her mummies, her statuary, her carvings, her jewels and her wall paintings. Their museums gained world renown because of these ill-gotten gains, while the countries of origin moldered, deprived not only of their natural riches, but also of their historic legacy. With the end of colonialism after World War II, the situation started righting itself, as now-properly abashed Western countries began returning these stolen treasures to their true homes.

The actual story is a bit different. The cultures that had created those treasures had long vanished by the time the Western collectors showed up and started sniffing around. Where once had been glory, now was abysmal poverty. More than that, there was a profound disinterest in the past. The citizens of Egypt, Greece, the Ottoman Empire, etc., cared nothing for the treasures beneath their feet. Those that they couldn’t see, they forgot; those that they could see, they recycled. They broke down ancient structures and used their stones to build their homes; they melted down ancient jewelry, and refashioned the gold in modern design. The Egyptian mummies to which thieves had easy access had long since vanished — some within days of being interred — especially since their wrappings made good paper and, for centuries, their dust was thought to have curative powers.

What made these remnants of the past valuable was the interest the West had in the ancient world’s past. To the Middle East, they were raw material; to the Westerners, things of beauty and wonder. And so the West took them away, to museums and private collections. In terms of what was happening in the Middle East 200 years ago or 100 years ago, Western activity was akin to digging in the garbage to collect someone else’s discards. The only thing that bespoke value in the regions themselves was gold, so the archeologists figured out that, if they gave to the fellahin who unearthed the ancient gold a sum of money equal to that object’s weight, the latter cheerfully parted with their cultural past.

The relics, once in the West, were treated with a reverence denied them in the lands from which they emerged. They were cleaned, restored, maintained, studied and much visited. And of course, as their status rose, the people who had so cavalierly parted with them realized that they had lost something of value. When they had achieved some measure of moral power, they demanded them back. Often, the West complied with those demands. …

[M]any ended up back at home, in lands governed by dictatorships. These, no matter how long they last, invariably seem to end in a welter of violence, flames, vandalism and theft. Is it a surprise, then, that when a dictatorship ends, it’s often the case that the treasures, once ignored and abused, then revered in foreign lands, and then returned to their natal soil, should be amongst the first casualties?

Statue of 18th Dynasty Pharoah Akhenaton, circa 1336 BC, recently looted from Egyptian museum and found two weeks later discarded beside a garbage bin.

06 Dec 2007

A magnesite or crystalline limestone figure of a lioness,

Elam, circa 3000-2800 B.C.

AFP:

A tiny and extremely rare 5,000-year-old white limestone sculpture from ancient Mesopotamia sold for 57.2 million dollars in New York on Wednesday, smashing records for both sculpture and antiquities.

The carved Guennol Lioness, measuring just over eight centimeters (3 1/4 inches) tall, was described by Sotheby’s auction house as one of the last known masterworks from the dawn of civilization remaining in private hands.

“It was an honor for us to handle The Guennol Lioness, one of the greatest works of art of all time,” Richard Keresey and Florent Heintz, the experts in charge of the sale, said in a joint statement.

“Before the sale, a great connoisseur of art commented to us that he always regarded the figure as the ‘finest sculpture on earth’ and it would appear that the market agreed with him,” they said.

Five different bidders, three on the telephone and two in the room, competed for the sculpture. The successful buyer was identified only as an English buyer who wished to remain anonymous.

The sale easily broke the previous record for the highest price for a sculpture at auction, which had stood at 29.1 million dollars and was set just last month at Sotheby’s in New York by Picasso’s “Tete de Femme (Dora Maar).”

It also beat the 28.6 million dollars paid for “Artemis and the Stag,” a 2,000-year-old bronze figure which sold also at Sotheby’s in New York in June and held the record for the most expensive antiquity to be sold at auction.

Described by Sotheby’s as diminutive in size, but monumental in conception, The Guennol Lioness was created around 5,000 years ago — around the same time as the first known use of the wheel — in the region of ancient Mesopotamia.

The piece was acquired by private collector Alastair Bradley Martin in 1948 and has been on display in New York’s Brooklyn Museum of Art ever since.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Antiquities' Category.

Feeds

|