Category Archive 'Cryptozoology'

25 Jun 2020

It’s been a long time since we’ve seen a new one of these.

04 May 2019

Better photos here: Guardian.

Nepal Army says: “Just a bear.” link

32″ long is awfully big.

01 Jul 2018

The last thylacine died in captivity in the zoo in 1936, or did it? People keep seeing them. Brooke Jarvis, in the New Yorker, wonders if the sightings are real, or if they simply represent expressions of the human hankering for the survival of a romantic critter.

Tasmania, which is sometimes said to hang beneath Australia like a green jewel, shares the country’s colonial history. The first English settlers arrived in 1803 and soon began spreading across the island, whose human and animal inhabitants had lived in isolation for more than ten thousand years. Conflict was almost immediate. The year that the Orchard farmhouse was built, the Tasmanian government paid out fifty-eight bounties to trappers and hunters who presented the bodies of thylacines, which were wanted for preying on the settlers’ sheep. By then, the number of dead tigers, like the number of live ones, was steeply declining. In 1907, the state treasury paid out for forty-two carcasses. In 1908, it paid for seventeen. The following year, there were two, and then none the year after, or the year after that, or ever again.

By 1917, when Tasmania put a pair of tigers on its coat of arms, the real thing was rarely seen. By 1930, when a farmer named Wilf Batty shot what was later recognized as the last Tasmanian tiger killed in the wild, it was such a curiosity that people came from all over to look at the body. The last animal in captivity died of exposure in 1936, at a zoo in Hobart, Tasmania’s capital, after being locked out of its shelter on a cold night. The Hobart city council noted the death at a meeting the following week, and authorized thirty pounds to fund the purchase of a replacement. The minutes of the meeting include a postscript to the demise of the species: two months earlier, it had been “added to the list of wholly protected animals in Tasmania.â€

Like the dodo and the great auk, the tiger found a curious immortality as a global icon of extinction, more renowned for the tragedy of its death than for its life, about which little is known. In the words of the Tasmanian novelist Richard Flanagan, it became “a lost object of awe, one more symbol of our feckless ignorance and stupidity.â€

But then something unexpected happened. Long after the accepted date of extinction, Tasmanians kept reporting that they’d seen the animal. There were hundreds of officially recorded sightings, plus many more that remained unofficial, spanning decades. Tigers were said to dart across roads, hopping “like a dog with sore feet,†or to follow people walking in the bush, yipping. A hotel housekeeper named Deb Flowers told me that, as a child, in the nineteen-sixties, she spent a day by the Arm River watching a whole den of striped animals with her grandfather, learning only later, in school, that they were considered extinct. In 1982, an experienced park ranger, doing surveys near the northwest coast, reported seeing a tiger in the beam of his flashlight; he even had time to count the stripes (there were twelve). “10 a.m. in the morning in broad daylight in short grass,†a man remembered, describing how he and his brother startled a tiger in the nineteen-eighties while hunting rabbits. “We were just sitting there with our guns down and our mouths open.†Once, two separate carloads of people, eight witnesses in all, said that they’d got a close look at a tiger so reluctant to clear the road that they eventually had to drive around it. Another man recalled the time, in 1996, when his wife came home white-faced and wide-eyed. “I’ve seen something I shouldn’t have seen,†she said.

“Did you see a murder?†he asked.

“No,†she replied. “I’ve seen a tiger.â€

As reports accumulated, the state handed out a footprint-identification guide and gave wildlife officials boxes marked “Thylacine Response Kit†to keep in their work vehicles should they need to gather evidence, such as plaster casts of paw prints. Expeditions to find the rumored survivors were mounted—some by the government, some by private explorers, one by the World Wildlife Fund. They were hindered by the limits of technology, the sheer scale of the Tasmanian wilderness, and the fact that Tasmania’s other major carnivore, the devil, is nature’s near-perfect destroyer of evidence, known to quickly consume every bit of whatever carcasses it finds, down to the hair and the bones. Undeterred, searchers dragged slabs of ham down game trails and baited camera traps with roadkill or live chickens. They collected footprints, while debating what the footprint of a live tiger would look like, since the only examples they had were impressions made from the desiccated paws of museum specimens. They gathered scat and hair samples. They always came back without a definitive answer.

In 1983, Ted Turner commemorated a yacht race by offering a hundred-thousand-dollar reward for proof of the tiger’s existence. In 2005, a magazine offered 1.25 million Australian dollars. “Like many others living in a world where mystery is an increasingly rare thing,†the editor-in-chief said, “we wanted to believe.†The rewards went unclaimed, but the tiger’s fame grew.

RTWT

26 May 2018

Great Falls Tribune:

On May 16 a lone wolf-like animal was shot and killed on a ranch outside Denton. With long grayish fur, a large head and an extended snout, the animal shared many of the same characteristics as a wolf; but its ears were too large, it’s legs and body too short, its fur uncharacteristic of that common to a wolf.

So far, the exact species is a mystery

So what was it? At this point, no one is 100 percent sure.

“We have no idea what this was until we get a DNA report back,” said Bruce Auchly, information manager for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. “It was near a rancher’s place, it was shot, and our game wardens went to investigate. The whole animal was sent to our lab in Bozeman. That’s the last I ever heard of it.”

Social media from around the Lewistown area was buzzing last week; with many people chiming in on what they believed the creature to be.

Grizzly cub? Dogman? Dire wolf? Or what?

“That’s a grizzly cub,” one commentator wrote. “Under a year and starving from the look.”

“Maybe a dire wolf,” wrote another, “because I don’t believe they are all gone.”

Speculation roamed as far as identifying that animal as a crypto-canid species said to roam the forests of North America.

RTWT

01 Dec 2017

Himalayan brown bear

Science:

Hikers in Tibet and the Himalayas need not fear the monstrous yeti—but they’d darn well better carry bear spray. DNA analyses of nine samples purported to be from the “abominable snowman†reveal that eight actually came from various species of bears native to the area.

In the folklore of Nepal, the yeti looms large. The creature is often depicted as an immense, shaggy ape-human that roams the Himalayan hinterlands. Purported sightings over the years, as well as scattered “remains†secreted away in monasteries or held by shamans, have hinted to some that the yeti is not merely a mythical boogeyman.

But science has not borne this out so far. Previous genetic analyses of a couple of hair samples collected in India and Bhutan suggested that one small stretch of their mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)—the genetic material in a cell’s power-generating machinery that’s passed down only by females—resembled that of polar bears. That finding hinted that a previously unknown type of bear, possibly a hybrid between polar bears and brown bears, could be roaming the Himalayas, says Charlotte Lindqvist, an evolutionary biologist at the State University of New York in Buffalo.

To find out for sure, Lindqvist and her colleagues took a more thorough look at the mtDNA of as many samples of supposed yeti remains as she could get her hands on. Some were obtained when she worked with a U.K. production crew on the 2016 documentary Yeti or Not?, which sought to sift fact from folklore. The filmmakers got hold of a tooth and some hair collected on the Tibetan Plateau in the late 1930s, as well as a sample of scat from Italian mountaineer Reinhold Messner’s museum in the Tyrolean Alps. More recent samples included hair collected in Nepal by a nomadic herdsman and a leg bone found by a spiritual healer in a cave in Tibet. The team also analyzed samples recently collected from several subspecies of bears native to the area, including the Himalayan brown bear, the Tibetan brown bear, and the black bear. Altogether, the scientists analyzed 24 samples, including nine purported to be from yeti.

Of the nine “yeti†samples, eight turned out to be from bears native to the area, the researchers report today in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B. The other sample came from a dog.

RTWT

17 Sep 2016

The Express:

Amateur photographer Ian Bremner, 58, was driving around the Highlands in search of red deer – but stumbled instead across the remarkable sight of what appears to be Nessie swimming in the calm waters of Loch Ness.

The father-of-four spends most of his weekends in the region taking photographs of the stunning natural beauty.

But it was not until he got back to his home in Nigg, Invergordon, that he noticed three humps emerging from the water which he thinks could be the elusive monster.

The picture shows a two-yard long silver creature swimming away from the lens with its head bobbing away and a tail flapping a yard away, preparing to swim further on.

The likely creature was spotted coming up for air close to the banks of the loch on Saturday afternoon midway between the villages of Dores and Inverfarigaig.

Whole thing.

These tend to fakes.

02 Sep 2016

National Geographic reports that the Westbrook, Maine snakeskin has been identified as coming from a Green Anaconda.

August 21st — Snakeskin story

Westbrook officials sent a sample of the snakeskin off to John Palcyk, a biologist at the University of Texas at Tyler, for genetic analysis. Placyk then sequenced the skin’s mitochondrial genome and found that it belonged to an anaconda—a shocking find that officials announced on August 30.

“It was pretty unexpected, I’ll tell you that,†Palcyk said to Steve Annear of the Boston Globe. “This was a 100 percent match to an anaconda.â€

To refine the ID, Placyk sent along his sequence to Jesús Rivas, an anaconda expert at New Mexico Highlands University, who compared it to a genetic database of anacondas from across South America.

In a phone call, Rivas says that the skin belongs to a female green anaconda (Eunectes murinus) that’s at least 10 to 12 years old, based on the skin’s size. The snake’s genetic quirks also suggest that its ancestors were most likely from Peru or Bolivia, though the snake probably was bred in the United States. (Find out more about green anacondas—the world’s largest snakes, pound for pound.)

So how did the snake end up in Maine?

First, it’s still not clear whether the skin’s placement was an elaborate hoax meant to stoke Wessie hype. But if Westbrook is legitimately home to a loose anaconda, Lally thinks that it was released into the wild by its owners, perhaps because they could no longer care for it.

“It would have had to come from someone who either caught it or bought it somewhere, brought it here, and then decided to let it go, for some reason,†he says.

The green anaconda can grow up to 20 feet long and weigh a whopping 200 pounds. That’s a big body to feed. And the world’s largest rodent, the capybara, is the perfect entree.

This sort of reptile buyer’s remorse is rare in Maine, says Lally, but it happens elsewhere in the United States. In Florida, the phenomenon has contributed to a booming—and ecologically disastrous—population of Burmese pythons in the Everglades, an invasive group seeded mostly by the 1992 destruction of a reptile breeding facility by Hurricane Andrew. (Find out how pythons have wreaked havoc on Florida’s native wildlife.)

But given the snake’s size and age, Rivas suspects that its owners were dedicated, and he maintains instead that the anaconda got out of its enclosure. “People who have a snake of this size normally are responsible keepers, [and] it’s very unlikely that they don’t have the awareness that the snake won’t survive in the wild,†says Rivas. “I doubt that it was released; more likely, it escaped.â€

If Wessie’s owners accidentally lost her, however, there’s a good reason why they aren’t putting up “lost pet†signs: It’s illegal in Maine to own an anaconda.

Regardless, Maine’s bitterly cold winter ensures that the snake’s escape will be brief, one way or another. In the wild, Rivas says that anacondas aren’t found in areas with temperatures below 72°F. Temperatures below 50°F are considered fatal, and night temperatures in Maine are poised to cross that threshold.

“If there is an anaconda, it’ll be dead pretty soon,†says Lally.

Lally adds that the snake doesn’t pose a major public safety threat, though he recommends that people not let their dogs and cats loose along the Presumpscot River. In the meantime, officials continue to look for the snake—and Rivas remains hopeful that they can catch it alive and unharmed.

“It’s a curiosity, not a crisis,†says Rivas. “The only one in danger here is the anaconda.â€

Full story.

Hat tip to Karen L. Myers.

21 Aug 2016

Bangor Daily News:

Westbrook police are warning residents after a large snake skin was found near the Presumpscot River on Saturday.

Police said a resident reported finding a shed snake skin along the Presumpscot River around 3 p.m. near the carry-in boat launch in the area of Riverbank Park.

Westbrook police officers photographed, collected and tagged the skin, which will be examined in attempts to determine what type of snake it came from and what risks this type of snake poses to public safety. …

This comes after two Westbrook police officers spotted a 10-foot snake eating a large mammal along the riverbank in Riverbank Park in June.

——————————

Since June, the snake has developed a following. It’s been named “Wessie.” It has a Twitter page. And the local Mast Landing Brewery created a “Wessie” IPA in its honor. Wessie beer was so popular that Mast Landing had sold out of it as of August 4th.

14 Mar 2016

La Bête du Gévaudan (Aquatint engraving), 1764.

Wikipedia:

The Beast of Gévaudan [was] the man-eating gray wolf, dog or wolfdog which terrorised the former province of Gévaudan (modern-day département of Lozère and part of Haute-Loire), in the Margeride Mountains in south-central France between 1764 and 1767. The attacks, which covered an area stretching 90 by 80 kilometres (56 by 50 mi), were said to have been committed by a beast or beasts that had formidable teeth and immense tails according to contemporary eyewitnesses.

Victims were often killed by having their throats torn out. The Kingdom of France used a considerable amount of manpower and money to hunt the animals; including the resources of several nobles, soldiers, civilians, and a number of royal huntsmen.

The number of victims differs according to sources. In 1987, one study estimated there had been 210 attacks; resulting in 113 deaths and 49 injuries; 98 of the victims killed were partly eaten. However, other sources claim it killed between 60 to 100 adults and children, as well as injuring more than 30.

14 Aug 2015

New Falcon Herald:

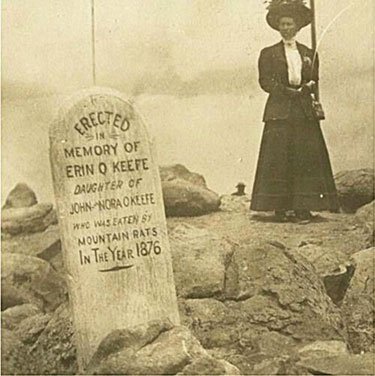

Pikes Peak was the scene of a fraud perpetrated in 1876 by John O’Keefe, whose job was to take weather readings on the summit and signal them to the city below.

O’Keefe’s tall tale about rats on the peak’s summit was first printed in the Pueblo Chieftain newspaper. The tale then spread to the Rocky Mountain News, which published an articled entitled “Rodents on the Rampage – an Awful and Almost Incredible Story, a Fight for Life with Rats on Pikes Peak.”

In the Rocky Mountain News story, O’Keefe claimed the top of Pikes Peak was overrun by rats the size of cats that fed on “saccharine gum that percolates through the pores of the rocks.”

The story continues:

“Since the establishment of the government’s signal station on the summit of the peak, these animals have acquired a voracious appetite for raw and uncooked meat, the scent of which seems to impart to them a ferocity rivaling the fierceness of the starved Siberian wolf.”

O’Keefe claimed that on his first night at the station, he and his wife were attacked by rats and would have been overwhelmed had they not electrocuted them using electrical wire powered by a battery.

When the battle was over, they discovered the rats had eaten their infant daughter, Erin.

O’Keefe claimed he buried all that was left of Erin (her skull) under a pile of rocks with a marker and this inscription, “Erin O’Keefe, daughter of John and Nora O’Keefe, who was eaten by mountain rats in the year 1876.”

The grave became a popular tourist attraction, and O’Keefe charged 50 cents for tourists to have their picture taken at the site.

O’Keefe was eventually revealed as a fraud. He didn’t have a wife or daughter, and probably buried his dead burro under the rocks.

Via Ratak Monodosico.

09 May 2015

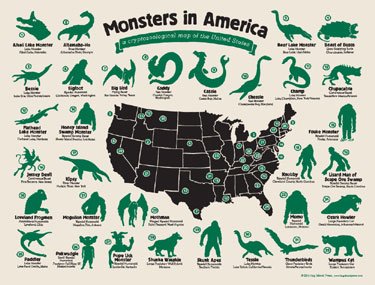

Disinformation links the Hog Island Press Cryptozoological Map of the United States, which is at least amusing.

Some states haven’t got any imaginary monsters. Connecticut and Rhode Island, for instance, are out of luck. Pennsylvania gets Thunderbirds, which I and Wikipedia have never heard of.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Cryptozoology' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|