Category Archive 'Death'

13 May 2024

On May 11 in 1819, Thomas Jefferson wrote about making peace with his slow descent toward death.

A decline of health, at the age of 76, was naturally to be expected,” he wrote, “and is a warning of an event which cannot be distant, and whose approach I contemplate with little concern. For indeed in no circumstance has nature been kinder to us than in the soft gradations by which she prepares us to part willingly with what we are not destined always to retain.

“First one faculty is withdrawn and then another, sight, hearing, memory, eucrasy, affections, and friends, filched one by one till we are left among strangers, the mere monuments of times past, and specimens of antiquity for the observation of the curious.”

14 Sep 2021

Written by CS Lewis in 1948.

“ ‘How are we to live in an atomic age?’ I am tempted to reply: Why, as you would have lived in the sixteenth century when the plague visited London almost every year, or as you would have lived in a Viking age when raiders from Scandinavia might land and cut your throat any night; or indeed, as you are already living in an age of cancer, an age of chronic pain, an age of paralysis, an age of air raids, an age of railway accidents, an age of motor accidents.

In other words, do not let us begin by exaggerating the novelty of our situation. Believe me, dear sir or madam, you and all whom you love were already sentenced to death before the atomic bomb was invented: and quite a high percentage of us were going to die in unpleasant ways.

It is perfectly ridiculous to go about whimpering and drawing long faces because the scientists have added one more chance of painful and premature death to a world which already bristled with such chances and in which death itself was not a chance at all, but a certainty.

The first action to be taken is to pull ourselves together. If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb, let that bomb when it comes find us doing sensible and human things—praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing the children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends over a pint and a game of darts—not huddled together like frightened sheep and thinking about death. They may break our bodies (a microbe can do that) but they need not dominate our minds.”

30 Aug 2016

Social media sites like Facebook and Twitter are already littered with the accounts of members who have passed away. Inevitably, some decades in the future, the number of accounts of the dead will exceed those of living users. What should social media sites do about that?

NDKane discusses the possibilities.

31 May 2016

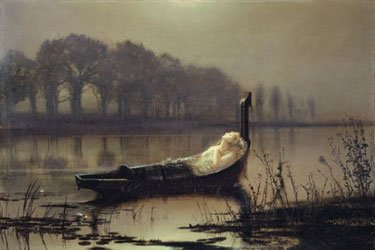

John Atkinson Grimshaw, The Lady of Shalott, 1875, Yale Center for British Art.

Cold hands

Beautiful face

Missing slippers

Wrist fevers

Night brain

Going outside at night in Italy

Shawl insufficiency

Too many pillows

Garden troubles

Someone said “No†very loudly while they were in the room

Letter-reading fits

Drawing-room anguish

Not enough pillows

Haven’t seen the sea in a long time

Too many novels

Pony exhaustion

Strolling congestion

Sherry served too cold

Ship infidelity

Spent more than a month in London after growing up in Yorkshire

Clergyman’s dropsy

Flirting headaches

River unhappiness

General bummers

Knitting needles too heavy

Mmmf

Beautiful chestnut hair

Spinal degeneration as a result of pride

Parents too happy

The Unpleasantness

From The Toast via Lucy Bellerby.

24 Apr 2016

Pieter Hintjens, 1962-

Pieter Hintjens is a (half-Scottish) Belgian software developer, aged 53, who is suffering from metastasized bile duct cancer. Being who he is, he naturally published on his blog a “protocol,” explaining his identity and circumstances and indicating how other people and he himself ought, in his view, to deal with the situation.

The contemporary supergeek is an unusual and exotic variant subspecies of humanity, and his protocol, I thought, illustrates particularly vividly that subgroup’s characteristic strengths and weaknesses.

I am, finally, so glad I never quit Belgium. This country allows for death on demand, for patients who are terminal or have a bad enough quality of life. It takes three doctors and a psychiatrist, in the second case, and four weeks’ waiting period. In the first case, it takes one doctor’s opinion.

My dad chose this, and died on Easter Tuesday. Several of us his family were with him. It is a simple and peaceful process. One injection sent him to sleep, into a coma. The second stopped his heart. It was a good way to die, and though I didn’t know I was sick then, one I already wanted.

I’m shocked that in 2016 few countries allow this, and enforce the barbaric torture of decay and failure. It’s especially relevant for cancer, which is a primary cause of death. Find a moment in your own jurisdiction, if it bans euthanasia, to lobby for the right to die in dignity.

19 Feb 2015

Oliver Sachs shares some bad news he received recently in the New York Times.

A month ago, I felt that I was in good health, even robust health. At 81, I still swim a mile a day. But my luck has run out — a few weeks ago I learned that I have multiple metastases in the liver. Nine years ago it was discovered that I had a rare tumor of the eye, an ocular melanoma. Although the radiation and lasering to remove the tumor ultimately left me blind in that eye, only in very rare cases do such tumors metastasize. I am among the unlucky 2 percent.

I feel grateful that I have been granted nine years of good health and productivity since the original diagnosis, but now I am face to face with dying. The cancer occupies a third of my liver, and though its advance may be slowed, this particular sort of cancer cannot be halted.

It is up to me now to choose how to live out the months that remain to me. I have to live in the richest, deepest, most productive way I can. In this I am encouraged by the words of one of my favorite philosophers, David Hume, who, upon learning that he was mortally ill at age 65, wrote a short autobiography in a single day in April of 1776. He titled it “My Own Life.â€

“I now reckon upon a speedy dissolution,†he wrote. “I have suffered very little pain from my disorder; and what is more strange, have, notwithstanding the great decline of my person, never suffered a moment’s abatement of my spirits. I possess the same ardour as ever in study, and the same gaiety in company.â€

Read the whole thing.

06 Jan 2015

For the morbid, those yearning to be horrified, or the merely curious, the New York Post reviews, Working Stiff, the memoir of New York Medical Examiner Judy Melinek (written with T.J. Mitchell).

Some of the deaths described are Darwin Award winners, others (like the chap tossed down an open manhole who landed in a pool of boiling water) are absolutely bloodcurdling to contemplate, while others are merely anecdotally intriguing.

There was the subway jumper at Union Square, for example, whose body was recovered on the tracks of the uptown 4 train with no blood — none at the scene, none in the body itself. She’d never seen anything like it, and only CME Hirsch could explain: The massive trauma to the entire body caused the bone marrow to absorb all the blood.

“Everyone in the room agreed,†Melinek writes, “that I had the coolest case of the day.â€

Finding a bullet for a gunshot wound, meanwhile, can be particularly baffling. Melinek says her favorite is “bullet embolusâ€: “A slug enters the beating heart at just the right spot and with precisely enough momentum to get flushed into the circulatory system, then surfs through smaller and smaller vessels until it gets stuck somewhere far removed from its point of entry.â€

In one case, a man was shot in the chest, but the bullet was found in his liver.

During her tenure, the most popular suicide spot in New York City was the atrium in Times Square’s Marriott Marquis hotel. Melinek autopsied two jumpers: One, a 26-year-old man, leapt from the 43rd floor.

His right arm and left leg were recovered on the 11th floor, his other two limbs on the seventh floor, and part of his skull wound up in the elevator shaft.

Her other jumper, also a man, jumped from the 23rd floor. One leg was found on the 10th floor, his torso on the ninth.

“I suspect these people imagine they are going to plummet gracefully down and land with a melodramatic thump in the lobby,†Melinek writes, “but I never saw that result. The ones I saw had pinballed off a variety of jutting structures on the way, each impact causing damage to a different plane of the body. Not graceful at all.â€

Read the whole thing.

01 Dec 2014

Baby Boomers will increasingly find handy David Eagleman’s 2006 start-up, Deathswitch described at Wired.

“At the beginning of the computer era, people died with passwords in their heads.â€

It was an administrative nightmare, with emails, photos, diaries, and financial information locked away for all eternity simply because people kept crossing into the beyond with the only set of keys. Eventually, Eagleman writes, a solution emerged: software called Death Switches that would detect a person’s demise and send prewritten, postmortem emails to next of kin, sharing passwords. But it didn’t take long, Eagleman goes on, for people to realize they could communicate more than passwords. They could say good-bye or get in the last word of an argument.

As it turns out, Eagleman wasn’t just writing fiction. In 2006 he launched a real-life startup, Deathswitch, to provide the service. Subscribers are prompted periodically via email to make sure they’re still alive. When they fail to respond, Deathswitch starts firing off their predrafted notes to loved ones. The company now has thousands of users and effectively runs itself. Among the perks of a premium Deathswitch account is the ability to schedule emails for delivery far in the future: to wish your wife a happy 50th wedding anniversary, for example, 30 years after you left her a widow.

Death is the original other dimension—a parallel universe that, for millennia, we have anxiously tried to understand. As software, Deathswitch is relatively simple, but as a tool in that millennia-long project it can feel spine-chillingly disruptive. Eagleman has jury-rigged a way for people to speak from beyond that inviolable border and—for those of us still sticking it out on this side—to feel we’re being spoken to. It’s another example of technology enabling things that previously would have seemed magic.

Hat tip to the Dish.

25 Sep 2014

Responding to Ezekiel Emanuel’s “I Want to Die at 75” Atlantic essay, Andrew Sullivan wonders: What Is the Best Way to Die?

John Buchan did an excellent job, I think, of describing the best possible death in The Half-Hearted (1900): Lewis Haystoun dying in the course of single-handedly delaying the Russian invasion of India at a narrow pass in the Hindu Kush, rifle in hand.

The fire died down to embers and a sudden scattering of ashes woke him out of his dreaming. The old Scots land was many thousand miles away. His past was wiped out behind him. He was alone in a very strange place, cut off by a great gulf from youth and home and pleasure. For an instant the extreme loneliness of an exile’s death smote him, but the next second he comforted himself. The heritage of his land and his people was his in this ultimate moment a hundredfold more than ever. The sounding tale of his people’s wars, one against a host, a foray in the mist, a last stand among the mountain snows, sang in his heart like a tune. The fierce, northern exultation, which glories in hardships and the forlorn, came upon him with such keenness and delight that, as he looked into the night and the black unknown, he felt the joy of a greater kinship. He was kin to men lordlier than himself, the true-hearted who had ridden the King’s path and trampled a little world under foot. To the old fighters in the Border wars, the religionists of the South, the Highland gentlemen of the Cause, he cried greeting over the abyss of time. He had lost no inch of his inheritance. Where, indeed, was the true Scotland? Not in the little barren acres he had left, the few thousands of city-folk, or the contentions of unlovely creeds and vain philosophies. The elect of his race had ever been the wanderers. No more than Hellas had his land a paltry local unity. Wherever the English flag was planted anew, wherever men did their duty faithfully and without hope of little reward, there was the fatherland of the true patriot.

The time was passing, and still the world was quiet. The hour must be close on midnight, and still there was no sign of men. For the first time he dared to hope for success. Before, an hour’s delay was all that he had sought. To give the north time for a little preparation, to make defence possible, had been his aim; now with the delay he seemed to see a chance for victory. Bardur would be alarmed hours ago; men would be on the watch all over Kashmir and the Punjab; the railways would be guarded. The invader would find at the least no easy conquest. When they had trodden his life out in the defile they would find stronger men to bar their path, and he would not have died in vain. It was a slender satisfaction for vanity, for what share would he have in the defence? Unknown, unwept, he would perish utterly, and to others would be the glory. He did not care, nay, he rejoiced in the brave obscurity. He had never sought so vulgar a thing as fame. He was going out of life like a snuffed candle. George, if George survived, would know nothing of his death. He was miles beyond the frontier, and if George, after months of war, should make his way to this fatal cleft, what trace would he find of him? And all his friends, Wratislaw, Arthur Mordaunt, the folk of Glenavelin, no word would ever come to them to tell them of his end. …

For in this ultimate moment he at last seemed to have come to his own. The vulgar little fears, which, like foxes, gnaw at the roots of the heart, had gone, even the greater perils of faint hope and a halting energy. The half-hearted had become the stout-hearted. The resistless vigour of the strong and the simple was his. He stood in the dark gully peering into the night, his muscles stiff from heel to neck. The weariness of the day had gone: only the wound in his ear, got the day before, had begun to bleed afresh. He wiped the blood away with his handkerchief, and laughed at the thought of this little care. In a few minutes he would be facing death, and now he was staunching a pin-prick.

He wondered idly how soon death would come. It would be speedy, at least, and final. And then the glory of the utter loss. His bones whitening among the stones, the suns of summer beating on them and the winter snowdrifts decently covering them with a white sepulchre. No man could seek a lordlier burial. It was the death he had always craved. From murder, fire, and sudden death, why should we call on the Lord to deliver us? A broken neck in a hunting-field, a slip on rocky mountains, a wounded animal at bay, such was the environment of death for which he had ever prayed. But this; this was beyond his dreams.

And with it all a great humility fell upon him. His battles were all unfought. His life had been careless and gay; and the noble commonplaces of faith and duty had been things of small meaning. He had lived within the confines of a little aristocracy of birth and wealth and talent, and the great melancholy world scourged by the winds of God had seemed to him but a phrase of rhetoric. His creeds and his arguments seemed meaningless now in this solemn hour; the truth had been his no more than his crude opponent’s! Had he his days to live over again he would look on the world with different eyes. No man any more should call him a dreamer. It pleased him to think that, half-hearted and sceptical as he had been, a humorist, a laughing philosopher, he was now dying for one of the catchwords of the crowd. He had returned to the homely paths of the commonplace, and young, unformed, untried, he was caught up by kind fate to the place of the wise and the heroic.

24 Oct 2009

The third time is enemy action, asserts the old Intelligence Community saying.

The Mirror:

A British nuclear expert taking part in disarmament talks with Iran has died in mysterious circumstances at a UN building in Austria.

Timothy Hampton, 47, plunged to his death from the 17th floor and was found in a stairwell just hours before high-level discussions were due to resume in Vienna.

Investigators said they have not ruled out murder or suicide, but local sources said no suicide note was found.

Police are also investigating the death of another Brit who fell from the same building four months ago.

The third such incident will be very hard to take for just another accident.

/div>

Feeds

|