Category Archive 'France'

09 Jun 2018

François Mitterrand, 1916-1996

One of the items I was reading yesterday in connection with the death of Anthony Bourdain referenced this must-read Esquire article on the last meal of French President François Mitterrand, dying of cancer in 1996. They were right: this is a great read.

He planned his annual pilgrimage to Egypt—with his mistress and their daughter—to see the Pyramids, the monumental tombs of the pharaohs, and the eroded Sphinx. Thats what his countrymen called him, the Sphinx, for no one really knew for sure who he was—aesthete or whoremonger, Catholic or athiest, fascist or socialist, anti-Semite or humanist, likable or despicable. And then there was his aloof imperial power. Later, his supporters simply called him Dieu—God.

He had come here for this final dialogue with the pharaohs—to mingle with their ghosts and look one last time upon their tombs. The cancer was moving to his head now, and each day that passed brought him closer to his own vanishing, a crystal point of pain that would subsume all the other pains. It would be so much easier … but then no. He made a phone call back to France. He asked that the rest of his family and friends be summoned to Latche and that a meal be prepared for New Year’s Eve. He gave a precise account of what would be eaten at the table, a feast for thirty people, for he had decided that afterward, he would not eat again.

“I am fed up with myself,” he told a friend.

And so we’ve come to a table set with a white cloth. An armada of floating wine goblets, the blinding weaponry of knives and forks and spoons. Two windows, shaded purple, stung by bullets of cold rain, lashed by the hurricane winds of an ocean storm.

The chef is a dark-haired man, fiftyish, with a bowling-ball belly. He stands in front of orange flames in his great stone chimney hung with stewpots, finely orchestrating each octave of taste, occasionally sipping his broths and various chorded concoctions with a miffed expression. In breaking the law to serve us ortolan, he gruffly claims that it is his duty, as a Frenchman, to serve the food of his region. He thinks the law against serving ortolan is stupid. And yet he had to call forty of his friends in search of the bird, for there were none to be found and almost everyone feared getting caught, risking fines and possible imprisonment.

But then another man, his forty-first friend, arrived an hour ago with three live ortolans in a small pouch—worth up to a hundred dollars each and each no bigger than a thumb. They’re brown-backed, with pinkish bellies, part of the yellowhammer family, and when they fly, they tend to keep low to the ground and, when the wind is high, swoop crazily for lack of weight. In all the world, they’re really caught only in the pine forests of the southwestern Landes region of France, by about twenty families who lay in wait for the birds each fall as they fly from Europe to Africa. Once caught—they’re literally snatched out of the air in traps called matoles—they;re locked away in a dark room and fattened on millet; to achieve the same effect, French kings and Roman emperors once blinded the bird with a knife so, lost in the darkness, it would eat twenty-four hours a day.

And so, a short time ago, these three ortolans—our three ortolans—were dunked and drowned in a glass of Armagnac and then plucked of their feathers. Now they lie delicately on their backs in three cassoulets, wings and legs tucked to their tiny, bloated bodies, skin the color of pale autumn corn, their eyes small, purple bruises and—here’s the thing—wide open.

When we’re invited back to the kitchen, that’s what I notice, the open eyes on these already-peppered, palsied birds and the gold glow of their skin. The kitchen staff crowds around, craning to see, and when we ask one of the dishwashers if he’s ever tried ortolan, he looks scandalized, then looks back at the birds. “I’m too young, and now it’s against the law,” he says longingly. “But someday, when I can afford one . . .” Meanwhile, Sara has gone silent, looks pale looking at the birds.

Back at the chimney, the chef reiterates the menu for Mitterrand’s last meal, including the last course, as he puts it, “the birdies.” Perhaps he reads our uncertainty, a simultaneous flicker of doubt that passes over our respective faces. “It takes a culture of very good to appreciate the very good,” the chef says, nosing the clear juices of the capon rotating in the fire. “And ortolan is beyond even the very good.”

RTWT

Ortolans do look tasty.

24 Apr 2018

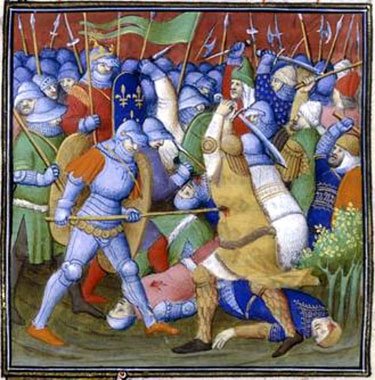

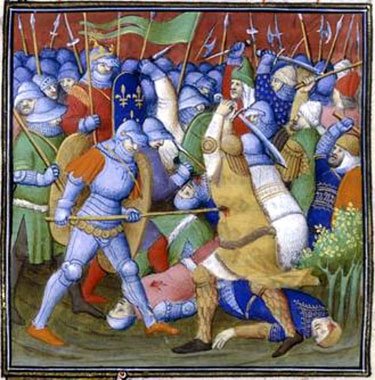

Battle of Poitiers.

Nulle Terre Sans Seigneur brings to our attention an interesting French political theorist who essentially visualized as the alternative to Absolutism the same sort of Noble Republic that once existed in Poland-Lithuania functioning, potentially with elective monarchy and all, on French soil. Fascinating reading.

By the time of early modernity, there were various ideas of which organ of the French constitution played a special role. The peerage had its strongest defender in the Duc de Saint-Simon. The absolutists and their insistence on monarchical supremacy were the orthodox school of thought. The Estates-General (defunct as of 1614 during the time Boulainvilliers was writing) and the parlements also had a few radical defenders of theirs, but they were not as influential — Claude de Seyssel’s Renaissance-era idea of a “balanced monarchy†having fallen out of favor, though the parlementaires did have their brief ascendancy during the Fronde.

[Henri, comte de] Boulainvilliers [1658-1722], in contrast, maintained a feudal theory of aristocratic anti-absolutism that the noblesse d’epee (sword nobility), originating from Frankish leudes, were the rightful representatives of the French nation, and though externally differentiated from commoners, were initially internally equal, as with the Polish szlachta. The pre-existing Gallican magnates, as survivors of the Roman magistracy, were entirely distinct from the French nation and its military character. The purpose of drawing this boundary was not to make an ethnic claim to sovereignty, but to underline the crucial link between war and the state. The “equality in inequality†of the pioneer French nobility and the right to judgment by peers which they had was eventually botched when the king, only a military chieftain at first, unduly extended his influence beyond the boundaries of the royal patrimony, and soiled the solidaristic maennerbund of the nobility by his creation of a peerage, the use of ennoblements to elevate free commoners (never more than emancipated serfs in Boulainvilliers’ view) into a courtier robe nobility, and other extra-constitutional measures. …

Now the more tempered defenders of royal absolutism did not deny that private justice was legitimate, but insisted that in this capacity they were acting only as royal justices and not as free magnates. One problem with this was its reliance on a modern, national conception of the nature of sovereignty. One moderate apologist of the French nobility, G.A. La Roque, in his “Traite de la noblesse†of 1678, pointed out that the tributary nature of a prince does not destroy his sovereignty, since there were many examples of kings themselves being vassals of greater lords or feudatories of some sort, while still exercising royal prerogative and displaying their own royal heraldry. Sicily and Ireland (as the Lordship of Ireland), for instance, were once papal fiefs, and acknowledged as such by the vassals invested with them. This implies that kings themselves are simply great magnates, undermining Filmerite assumptions of monarchical supremacy. This is not to say that reciprocal bonds and dues do not apply. …

The Salic law was simply the tribal law of the Salian Franks, and could not be used to justify hereditary succession as an essential component of the crown. Actually, merits of hereditary monarchy aside, ideas of elective kingship still flourished around the beginning of the Capetian dynasty, as the historian Charles-Petit Dutaillis documented in The Feudal Monarchy in France and England from the Tenth to the Thirteenth Century (1936):

The Archbishop of Rheims “chose the king†in accordance with the agreement previously arrived at by the great men of the kingdom before anointing and crowning him, and the subjects who thronged the cathedral, greater and lesser nobility alike, gave their consent by acclamation. Theoretically the unanimous choice of the whole kingdom was necessary for the election but, in fact, once the will of those who were of decisive importance was made clear, the approbation of others was merely a matter of form. Nevertheless the conventions of the chancery attached considerable importance to it ; the first year of the reign only began on the day of consecration and this rule, closely related to the theory of election, was to last for two centuries.

In fact, then, this Capetian kingship whose supernatural character we have been illustrating was, at the same time, elective. To the modern mind that may present a strange contradiction but contemporaries found no cause for surprise. The very fact that the kingship was so closely comparable to the priesthood justified its non-hereditary character. How could churchmen deny the divine nature of an institution because it was elective? Even bishops and popes were appointed by election. The monk Richer attributes to the Archbishop Adalberon a speech to the nobles in 987 which does not exactly represent the ideas of Adalberon but it is quite in accordance with the principles of the Church. “The kingdom,†he says, â€has never made its choice by hereditary right. No one should be advanced to the throne who is not outstanding for intelligence and sobriety as well as for a noble physique strengthened by the true faith and capable of great souled justice.†The best man must reign and, we may add, he must be chosen by the “best†men.

This was the theory of the Church without modification or limitation. Once he had been elected by a universal acclamation, which, in fact, represented the assent of a few individuals, and consecrated, he became king by the Grace of God commanding the implicit obedience of all.

Contemporaries like David Hume actually regarded Boulainvilliers to be a republican. This is an interesting question. Certainly, he envisioned the monarchy in voluntaristic and contractual terms. The Frankish warrior aristocracy was the source of power, and he thought that the noble freemen had the right to bind themselves to lords other than the reigning king if the latter did violence to their property. Royal succession was simply one of many private rights. There’s definitely a nativist element to the whole picture, and one could almost draw a parallel between his noble ideology of resistance to latter-day democratic nationalist conflicts with the ruling authorities of composite dynastic states. But what makes him separate is his insistence on the essential role of class divisions in a society. This is anathema not only to the democrats, but to many of the absolutists who want merely a neat bifurcation between sovereigns and subjects, but care little for the natural inequalities in subjects except insofar as they serve the reasons of state. If he seems progressive in some respects, he outflanks his opponents from the right in other, more crucial ways.

RTWT

Robert Heinlen’s concept of linking full, voting citizenship to military service (Starship Troopers 1959) is the essence of the same idea.

Boulainvilliers, in 17th century France, arguing for the implementation of the same political practices and philosophy operating immemorially in Poland, I would argue, demonstrates the existence, and subconscious cultural survival of a universal preliterate European political culture based on a hierarchical society with full civic participation and personal freedom based on military service and the skilled use of arms, featuring the fundamental equality of the warrior (noble, knightly) class, along with limited powers of monarchy and its potentially elective character. Compare the Greek warriors in The Iliad.

04 Feb 2018

Nice Adobe Spark essay on L’Equipage Mayennais, a French hunt that pursues wild boar with Anglo-French hounds. French hunting is “more chic than cruel.”

04 Jan 2018

Arnaud Florac at Boulevard Voltaire

La BBC a tourné une série sur la guerre de Troie et va la diffuser sur Netflix. Pas très original. Du coup, la chaîne publique britannique s’est rattrapée sur le casting : Achille sera joué par un Noir, en l’occurrence l’acteur David Gyasi. Je crois qu’au tournant de cette année, nous en sommes rendus au stade de l’allégorie. Tout y est. …

Ainsi donc, en 2018, retenez bien : Achille est noir, avoir un enfant est l’affaire de deux mamans ou de deux papas, les réfugiés syriens sont nés à Kaboul, le féminisme s’arrête à l’entrée du XVIIIe arrondissement, coucher avec une fille de 11 ans n’est pas si grave mais draguer sa voisine fait de vous un porc. Je ne crois pas que Huxley, Orwell, Dick ou Bradbury y croiraient. Ça marche trop bien, trop vite. Pas besoin de brûler les livres comme dans Fahrenheit 451 : plus personne ne les lit (à part les futurs classiques : Papi débranche sa perf ou Maman couche avec la boulangère). Pas besoin d’organiser les deux minutes de la haine, comme dans 1984 : il y a Twitter, qui fait ça très bien. « Le mensonge, c’est la vérité » : pas compliqué à faire avaler, dans un monde comme celui-ci.

“The BBC has filmed a series on the Trojan War and will broadcast it on Netflix. Not very original. Suddenly, the British public channel has gone all up-to-date on its casting: Achilles will be played by a black, in this case the actor David Gyasi. I believe that at this New Year, we have reached the stage of allegory. Everything is there. …

So, in 2018, note well: Achilles is black, having a child is the business of two moms or two dads, Syrian refugees were born in Kabul, feminism stops at the entrance of the eighteenth arrondissement, sleeping with an 11 year old girl is not so awful but flirting with her neighbor makes you a pig. I do not think Huxley, Orwell, Dick or Bradbury would believe it. Things change so far, so fast. No need to burn the books as in Fahrenheit 451: no one reads them (except for such future classics as: ‘Papa disconnects his IV’ or ‘Mom sleeps with the baker’). No need to organize the two minutes of hate, as in 1984: there is Twitter, which does it very well. ‘The lie is the truth’: not complicated to swallow, in a world like this.”

Note: In the Iliad, Achilles has blonde hair («ξανθῆς δὲ κόμης ἕλε ΠηλεÎωνα» = “she (Athena) grabbed Achilles by his blonde hair”; Iliad, 1.197). That’s probably the most persistent characteristic given for him and is repeated numerous times. The word “xanthÄ“” (ξανθή) can be translated as “yellow”, “fair”, “golden”, “blonde”.

LLTC

26 Jul 2017

Anne Dufourmantelle

New York Times:

A French philosopher and psychoanalyst, known for her work that praised living a life that embraced risk, died last week as a result of following her own bold philosophy.

The philosopher, Anne Dufourmantelle, 53, drowned on Friday as she tried to save two children who were struggling to swim off the coast of Pampelonne beach, near St.-Tropez, France, according to a report from French public television.

Ms. Dufourmantelle was on the beach when the weather began to change and the previously safe swimming area became treacherous. She saw two children who were in danger and leapt into the sea to help, according to France 3, before being caught in the rough surf.

She was pulled unresponsive from the water by two other swimmers, and attempts to resuscitate her failed.

Both children survived.

Ms. Dufourmantelle’s action harkened back to her own words.

“When there really is a danger that must be faced in order to survive…there is a strong incentive for action, dedication and surpassing oneself,†she said in a 2015 interview.

RTWT

HT: Frank Dobbs.

08 Jun 2017

French Serving Knife, c. late XVIth century. Designed to joint, slice, and serve venison.

20 May 2017

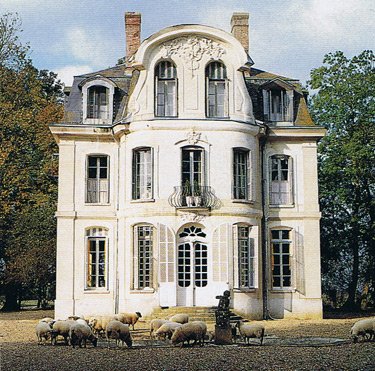

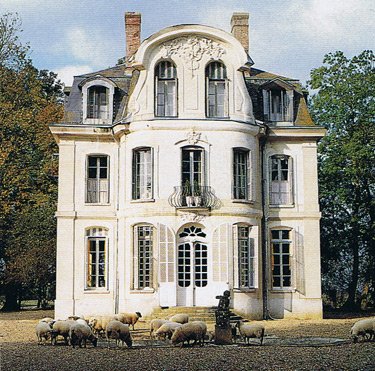

7 bedrooms, 6 full baths, 9-10 acres. Only €1,000,000 for the Chateau de Morsan, nestled in the midst of the forests of Normandy, one of the few remaining folies in France. Originally built around 1760 as a hunting lodge by the Marquis de Morsan, a confidant to Louis XV, for the King’s visit. The architect was Ange-Jacque Gabriel who was also the architect of the petit Trianaon at Versailles and the Folie of Madame de Pompadour, the mistress of the King.

The current owner rhapsodizes:

The house is a national monument, a summer house, not built for all seasons. There are two Renaissance towers, standing and three stables, all needing to be restored, and the windows and shutters on the house should be replaced by double glass, etc. The roof which is slate, needs rebuilding, as it is original, that can be done correctly with slate for around 200,000 euros. It has a nice servants cottage and quite a lot of land, it is very safe and protected there, two hours from Paris, and no one could find it. The land is quite fertile for growing vegetables, flowers, and herbs, and there is a very choice parcel of land with trees to build a large guest house, There are about nine or 10 acres, and is great for horses, it is horse country. It has everything.

With a good and responsible buyer who loves the l8th Century, and period furniture, the house can be sold more or less furnished at a very reasonable price. The furnishings are the right period for the house, so it could be sold furnished or semi furnished, to the right person.

A lovely couple reside onsite as caretakers. We have known their family for years, and the young man can do everything, he is very skilled and diversified, and does extra projects. She is very artistic, and keeps the house up.

It has important wood paneling and fireplaces, and it should not be changed or damaged, We can not sell the property to anyone who would destroy any of the original details, it has been maintained for nearly 300 years, and is a summer house. Central heating can be revived, there are radiators that function, and the plumbing should be brought up to date. This is not a house for the faint hearted, it is for a French history buff, and someone who wants to live in the beauty and charm of the l8th Century. I think that it would not appeal to most Americans, it is a romance with the past, and absolutely incredible in the summer… let’s say to die over… and absolutely unique. There are less than six of these l8th Century folies left in the country.â€

Handsome Properties International has the listing.

04 May 2017

The Week:

Le Pen claims the French presidential election is actually a choice between her and Angela Merkel.

Marine Le Pen, France’s far-right presidential candidate, pulled out a snappy line against centrist candidate Emmanuel Macron in a head-to-head presidential debate Wednesday evening. Le Pen, claiming Macron will cave to German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s will if he is elected, argued the contest was really a choice between which of two women would lead France: Either her or Merkel.

22 Apr 2017

Christopher Caldwell, in City Journal, discusses the untranslated three-book oeuvre of French commentator Christophe Guilluy, a specialist observer of French demographics, real estate, and economic developments, who describes the development, in France, of a similar practical separation and conflict of interests between the prosperous urban community of fashion elite and La France périphérique, the Gallic equivalent of Fly-Over America.

[T]he urban real-estate market is a pitiless sorting machine. Rich people and up-and-comers buy the private housing stock in desirable cities and thereby bid up its cost. Guilluy notes that one real-estate agent on the Île Saint-Louis in Paris now sells “lofts†of three square meters, or about 30 square feet, for €50,000. The situation resembles that in London, where, according to Le Monde, the average monthly rent (£2,580) now exceeds the average monthly salary (£2,300).

The laid-off, the less educated, the mistrained—all must rebuild their lives in what Guilluy calls (in the title of his second book) La France périphérique. This is the key term in Guilluy’s sociological vocabulary, and much misunderstood in France, so it is worth clarifying: it is neither a synonym for the boondocks nor a measure of distance from the city center. (Most of France’s small cities, in fact, are in la France périphérique.) Rather, the term measures distance from the functioning parts of the global economy. France’s best-performing urban nodes have arguably never been richer or better-stocked with cultural and retail amenities. But too few such places exist to carry a national economy. When France’s was a national economy, its median workers were well compensated and well protected from illness, age, and other vicissitudes. In a knowledge economy, these workers have largely been exiled from the places where the economy still functions. They have been replaced by immigrants. …

Top executives (at 54 percent) are content with the current number of migrants in France. But only 38 percent of mid-level professionals, 27 percent of laborers, and 23 percent of clerical workers feel similarly. As for the migrants themselves (whose views are seldom taken into account in French immigration discussions), living in Paris instead of Boumako is a windfall even under the worst of circumstances. In certain respects, migrants actually have it better than natives, Guilluy stresses. He is not referring to affirmative action. Inhabitants of government-designated “sensitive urban zones†(ZUS) do receive special benefits these days. But since the French cherish equality of citizenship as a political ideal, racial preferences in hiring and education took much longer to be imposed than in other countries. They’ve been operational for little more than a decade. A more important advantage, as geographer Guilluy sees it, is that immigrants living in the urban slums, despite appearances, remain “in the arena.†They are near public transportation, schools, and a real job market that might have hundreds of thousands of vacancies. At a time when rural France is getting more sedentary, the ZUS are the places in France that enjoy the most residential mobility: it’s better in the banlieues.

In France, the Parti Socialiste, like the Democratic Party in the U.S. or Labour in Britain, has remade itself based on a recognition of this new demographic and political reality. François Hollande built his 2012 presidential victory on a strategy outlined in October 2011 by Bruno Jeanbart and the late Olivier Ferrand of the Socialist think tank Terra Nova. Largely because of cultural questions, the authors warned, the working class no longer voted for the Left. The consultants suggested a replacement coalition of ethnic minorities, people with advanced degrees (usually prospering in new-economy jobs), women, youths, and non-Catholics—a French version of the Obama bloc. It did not make up, in itself, an electoral majority, but it possessed sufficient cultural power to attract one.

It is only too easy to see why a populist and nationalist revolt against the elite urban community of fashion is an international development.

A must-read.

02 Mar 2017

French Opium Party, 1918

/div>

Feeds

|