Samuel Whittemore 1695-1793

American Revolution, Battles of Lexington and Concord, Samuel Whittemore, The Right Stuff

250 Years Ago Today:

Born in 1695, just 75 years after the first Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock, the stone-cold hardass who would be made a state hero of Massachusetts was first unleashed on colonial America in the 1740s while serving as a Captain in His Majesty’s Dragoons – a badass unit of elite British cavalrymen much-feared across the globe for their ability to impale people on lance-points and then pump their already-dead bodies full of gigantic pistol ammunition that more closely resembled baseballs than the sort of rounds you see packed into Beretta magazines these days. Fighting the French in Canada during the War of Austrian Succession (a conflict that was known here in the colonies as King George’s War because seriously WTF did colonial Americans care about Austrian succession), Whittemore was part of the British contingent that assaulted the frozen shores of Nova Scotia and beat the shit out of the French at their stronghold of Louisbourg in 1745. The 50 year-old cavalry officer went into battle galloping at the head of a company of rifle-toting horsemen, and emerged from the shouldering flames of a thoroughly ass-humped Louisbourg holding a bitchin’ ornate longsword he had wrenched from the lifeless hands of a French officer who had, in Whittemore’s words, “died suddenly”. The French would eventually manage to snake Louisbourg back from the Brits, so thirteen years later, during the Seven Years’ War (a conflict that was known here in the colonies as the French and Indian War because WTF we were fighting the French and the Indians, and also because it lasted nine years instead of seven), Whittemore had to return to his old stomping grounds of Louisburg and ruthlessly beat it into submission once again. Serving under the able command fellow badass British commander James Wolfe, a man who earned his reputation by commanding a line of riflemen who held their lines against a frothing-at-the-mouth horde of psychotic, sword-swinging William Wallace motherfuckers in Scotland (this is a story I intend to tell at a later date), Whittemore once again pummeled the French retarded and stole all of their shit he could get his hands on. He served valiantly during the Second Siege of Louisbourg, pounding the poor city into rubble a second time in an epic bloodbath would mark the beginning of the end for France’s Atlantic colonies – Quebec would fall shortly thereafter, and the French would be chased out of Canada forever. So you can thank Whittemore for that, if you are inclined to do so.

Beating Frenchmen down with a cavalry saber at the age of 64 is pretty cool and all, but Whittemore still wasn’t done doing awesome shit in the name of King George the Third and His Loyal Colonies. Four years after busting up the French for the second time in two decades he led troops against Chief Pontiac in the bloody Indian Wars that raged across the Great Lakes region. Never one to back down from an up-close-and-personal fistfight, it was during a particularly nasty bout of hand-to-hand combat he came into possession of another totally sweet war trophy – an awesome pair of matched dueling pistols he had taken from the body of a warrior he’d just finished bayoneting or sabering or whatever.

After serving in three American wars before America was even a country, Whittemore decided the colonies were pretty damn radical, so he settled down in Massachusetts, married two different women (though not at the same time), had eight kids, and built a house out of the carcasses of bears he’d killed and mutilated with his own two hands. Or something like that.

Now, all of this shit is pretty god damned impressive, but interestingly none of it is actually what Samuel Whittemore is best known for. No, his distinction as a national hero instead comes from a fateful day in mid-April 1775, when the British colonies in the New World decided they weren’t going to take any more of King George’s bullshit and decided to get their American Revolution on. And you can be pretty damn sure that if there were asses to be kicked, Whittemore was going to be one of the men doing the kicking.

So one day a bunch of colonial malcontents got together, formed a battle line, and opened fire on a bunch of redcoats that were pissing them off with their silly Stamp Acts and whatnot. The Brits managed to beat back this militia force at the Battles of Lexington and Concord, but when they heard that a larger force of angry, rifle-toting colonials was headed their way, the English officers decided to march back to their headquarters and regroup. Along the way, they were hassled relentlessly by American militiamen with rifles and angry insults, though no group harassed them more ferociously than Captain Sam Whittemore. When the Redcoats went marching back through his hometown of Menotomy, this guy decided that he wasn’t going to let his advanced age stop him from doing some crazy shit and taking on an entire British army himself. The 80 year old Whittemore grabbed his rifle and ran outside:

Whittemore, by himself, with no backup, positioned himself behind a stone wall, waited in ambush, and then single-handedly engaged the entire British 47th Regiment of Foot with nothing more than his musket and the pure liquid anger coursing through his veins. His ambush had been successful – by this time this guy popped up like a decrepitly old rifle-toting jack-in-the-box, the British troops were pretty much on top of him. He fired off his musket at point-blank range, busting the nearest guy so hard it nearly blew his red coat into the next dimension.

Now, when you’re using a firearm that takes 20 seconds to reload, it’s kind of hard to go all Leonard Funk on a platoon of enemy infantry, but damn it if Whittemore wasn’t going to try. With a company of Brits bearing down in him, he quick-drew his twin flintlock pistols and popped a couple of locks on them (caps hadn’t been invented yet, though I think the analogy still works pretty fucking well), busting another two Limeys a matching set of new assholes. Then he unsheathed the ornate French sword, and this 80-year-old madman stood his ground in hand-to-hand against a couple dozen trained soldiers, each of which was probably a quarter of his age.

…[I]t didn’t work out so well. Whittemore was shot through the face by a 69-caliber bullet, knocked down, and bayonetted 13 times by motherfuckers. I’d like to imagine he wounded a couple more Englishmen who slipped or choked on his blood, though history only seems to credit him with three kills on three shots fired. The Brits, convinced that this man was sufficiently beat to shit, left him for dead kept on their death march back to base, harassed the entire way by Whittemore’s fellow militiamen.

Amazingly, however, Samuel Whittemore didn’t die. When his friends rushed out from their homes to check on his body, they found the half-dead, ultra-bloody octogenarian still trying to reload his weapon and seek vengeance. The dude actually survived the entire war, finally dying in 1793 at the age of 98 from extreme old age and awesomeness. A 2005 act of the Massachusetts legislature declared him an official state hero, and today he has one of the most badass historical markers of all time.

“Sweep the Leg”

Turkey Calling, Wild Turkey

Watching this my wife came to the conclusion that drink had been taken. I thought the turkey put up a good fight.

HT: Bernie Sanders (the CPA, not the communist).

Hold on to Your Seats!

Donald Trump, Economics, Free Trade, Protectionism, Smoot-Hawley Tariff, Tariffs

No one ever claimed tariff costs won’t get passed along to consumers. Trump thinks foreign countries will make deals cutting their own tariffs on US products and trade restrictions in return for our dropping ours, and it won’t be a major problem for long. Maybe so, maybe not. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, Priotectionism’s previous Last Hurrah, was rather less than a success.

I’d say: It’s obviously true that free trade benefits everyone. And it’s also true that Protectionism forces farmers, professionals, shopkeepers, &c. to pay more for many things to benefit industrial companies and factory workers. Lots of Americans have argued, not incorrectly, that this kind of privileging of some members of society at everyone else’s expense is immoral. But… we have seen, over decades now, the mass transfer of production, manufacturing, industry, and blue collar jobs overseas, resulting in the economic devastation, depopulation, and general ruin of cities, regions, communities. The small non-resort town, the small city or town lacking a college or university has become a wasteland, braindrained as the capable younger population was compelled to relocate to some portion of the Megalopolis, leaving behind a dysfunctional residuum of losers. The 19th Century Tories would have contended that noblesse oblige and national solidarity requires bearing some extra costs to keep the peasantry happy, prosperous, and in work. American Classical Liberalism is more Darwinian, but we Classical Liberals tend also to be agrarians who deplore the effeminacy and conformity of suburbia, the corruption and decadence of urban culture. Subsidizing the proletarians may be necessary to save civilization.

And, beyond that somewhat questionable argument, we do have the issue of National Defense. If we build just about everything overseas, inevitably one fine day, the balloon will go up, there will be war. Quite possibly with China. How inconvenient and embarrassing it will be when our adversaries decline to fill our new emergency orders for tanks, ships, and planes, which we find they can produce in profusion.

Cheap goods are a fine thing, but military capability and preparedness is decidedly a better thing.

In any case, of course, it’s out my hands and yours, 77 million voters put the decision in the hands of Donald J. Trump, who has had a Protectionist bee in his bonnet for a very long time.

It’s also been a long time, most of a century, that Free Trade has been in ascendance. Even the democrat party left gave up “protecting American workers’ jobs” long ago, hoping cheaper stuff at Walmart would suffice to keep them happy. But, now everything old is new again, and we are about to have an experiment in Protectionism one more time.

The Donald Trump theory of Industrial Revival, I’d say, has one key shortcoming: cheap labor. Back in the day, 1880-1920, America had that huge wave of immigration and those immigrants overwhelmingly came here willing to work and eager to take jobs Americans wouldn’t do. My ancestors came to Pennsylvania to work in the coal mines at a time when the casualty rate of deaths was on the scale of a small war and the survivors had lives shortened by miners’ asthma.

Those immigrants had lots of kids so American industry had lots of cheap, affordable labor.

Today, we’re in the middle of another huge wave of angry Nativism precipitated by the feckless and cynical policies of the democrats intentionally turning a blind eye and facilitating mass Third World immigration, then lavishing housing, health benefits, and welfare on illegals who in turn delivered a long series of front page stories of murders, rapes, drug dealing, and gang violence.

Meanwhile, a very large segment of the old American working class, in the traditional American way, has with passing generations moved up and out of the proletariat into management, the professions, and the bureaucracy.

Whether or not the kids-who-did-not-do-homework left behind in the falling-down ruins of rust bucket America are going to put down the meth pipe and start rising with the sun to answer the factory whistle remains to be seen. If I were Trump, I’d stop deporting illegals who are actually working right now.

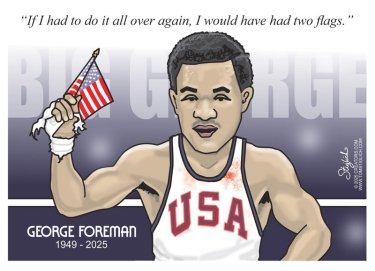

George Foreman 1949-2025

1968 Olympics, George Foreman, Obituaries, The Right Stuff

During their medal ceremony in the stadium in Mexico City during the Summer 1968 Olympic Games, two African-American athletes, Tommie Smith, who won the Gold Medal in the 200-meter running event, and John Carlos, who won the Bronze, each raised a fist in the Black Power Salute during the playing of the US national anthem.

George Foreman, after winning the Gold Medal in Heavyweight Boxing,took a small American flag and waved it to the four corners of the auditorium.

————————————-

“He Took the Idea of ‘Being Hard to Love’ as a Personal Challenge”

Alton Illinois, Kenneth Kenne Joseph Pluhar Jr., Obituaries

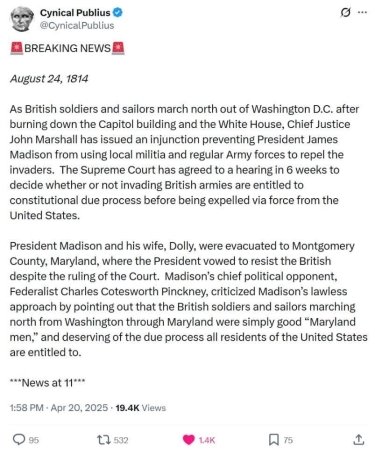

80,000 Kennedy Assassination Documents Released

Black Humor, Clinton Enemies Sudden Deaths, Hillary Clinton, JFK Assassination

Really Vital Question of the Day

Harry Potter, Kermit the Frog, Strategy

Granted, it’s a bit of a cliché, but I spend a lot of time thinking about what would happen if 100 Harry Potters faced off in a battle to the death against 1,000,000 unarmed Kermit the Frogs. (Like most men, I do this when not thinking about the Roman Empire.) Could the badly outnumbered Potters — their powerful magic best suited to dueling at close quarters — make a heroic stand against the onrushing green menace, or would hundreds of thousands of mindlessly determined frogs swarm the Hogwarts elite in an implacable amphibious wave?

Western civilization’s crude attempts to answer this question have heretofore been relegated to the arena of philosophical speculation, much as the learned medievals took to pondering how many angels could dance on the head of a pin. Until now. Ladies and gentlemen, I invite you to watch all one and a half minutes of this stunning simulation, undertaken using the finest technological modeling tools available to modern researchers, and discover the breathtaking truth. …

More.————————

100 Harry Potters vs 1 million Kermit the Frogs

byu/FeanorOath inGeeksGamersCommunity

—————————–The hundred Harrys are idiots. Running chaotically in an unorganized mass toward these overwhelming numbers of attackers is the precise opposite of the proper defensive technique.

First of all, we need a straight line of Harrys presenting the maximum frontage of firepower.

We commence by laying down a heavy and devastating barrage of fire, wiping out the nearest Kermits and causing their cadavers to impede briefly their comrades’ charge.

We retire slowly, while at the time more rapidly withdraw, each Harry by Harry at both ends of the line.

While retreating, every even number Harry is firing fire bombs into the mass of Kermits, while every even Harry creates his own portion of a line of defensive obstacles.

The more rapidly moving ends of the line close backwards creating a closed circle.

In essence, Harrys continue to fire on the enemy and other Harrys slow the enemy, while the full set of Harrys arranges itself in a defensive circle.

We finally take a third of Harrys and use them to build an internal final redout and to form a reserve.

And we then proceed to dissect all the froggies.