Category Archive 'The Elite'

12 Jul 2017

High Culture, according to David Brooks

“Recently I took a friend with only a high school degree to lunch. Insensitively, I led her into a gourmet sandwich shop. Suddenly I saw her face freeze up as she was confronted with sandwiches named ‘Padrino’ and ‘Pomodor’ and ingredients like soppressata, capicollo and a striata baguette. I quickly asked her if she wanted to go somewhere else and she anxiously nodded yes and we ate Mexican.â€

— David Brooks, “How We Are Ruining America,†New York Times, 7/11/17

McSweeney’s has published the Course Catalog for David Brooks’ Elite Sandwich College:

Classic Italian Meats 205

Prerequisite: Basic Deli Meats 101

In this class we will go beyond the American deli meats like ham, turkey, and chicken breast and learn more in-depth about the classic Italian cured meats: Pancetta, Prosciutto, Capicola, and more. Students will learn about origin, curing techniques, and appropriate stacking method. Two lectures and two studio hours each week.

Fancy Condiments and Toppings 305

Prerequisite: Mayonnaise and Mustard Only 101

Students will learn the basics of topping a sandwich beyond just meat and vegetables. Techniques include the seasoned olive oil drizzle and distribution of aioli. If time in semester permits, students will dabble in use of cornichons and castelvetranos. Three lectures and one lab weekly.

Wrapping 101

A perfect sandwich wrap takes skills. This likely wasn’t covered in your basic high school sandwich courses. Wrapping techniques discussed include old style deli-fold, long breads, and double layer. Lab only.

Talking to Your Friends About Italian Delis 426

In this soft-skills class, students will learn how to help friends who have never visited a deli choose items on the menu. Students will learn how to gently correct friends when they pronounce “mozzarella†with the “a†sound at the end, when the right time is to explain that tomatoes were actually not native to Europe so marinara sauce is actually not traditionally Italian, and the right way to introduce that pizza is actually very different in Italy. Three lectures weekly. Includes unannounced quizzes/sandwich runs.

17 May 2017

Trink forwards the comments of Anonymous:

He’s a loose cannon. He doesn’t know what he’s doing. He’s bumbling, fumbling, crude, rude, and the proverbial bull in an historic china shop.

The biggest complaint about the president is that he’s not presidential. How can he tweet? Yeah, Comey needed to be fired. Hell, he begged to be fired, but you don’t do it like that. It’s amateur hour.

Donald Trump’s demeanor has not only been dissected 18 hours a day since January 20th, it has been probed, prodded, and generally autopsied since he stirred up the 17-man field in the GOP primaries. There is nothing revelatory remaining.

If Washington loved “No Drama†Obama, it loathes “Quick to Jump†Trump. The Capital City has long been referred to as Hollywood for Ugly People, but we’ve entered a new era of performance art. It has become style over substance to the Nth degree.

The majority of the press, the commentariat and the professional class of teat suckers are just appalled, I mean appalled that man was ever allowed in the Oval Office. Yeah, he’s rich, but he’s tasteless rich. If Crotch-Scratch Joe from the trailer park down by the tracks won the lottery his place would look like Trump’s New York apartment.

And that’s the real sin, isn’t it? The four richest counties in America now surround the Federal City. The New York Times ran a story Friday about how property prices have soared surrounding the District and how well Aston Martins and McLarens are selling. See, we’re talking taste.

Meanwhile, across the country in Los Angeles county a new private terminal is opening for the super rich at LAX, replete with comfortable furniture, beds, fine wines and chocolate, a masseuse on call and, of course, a more refined TSA experience. But more than that there is an iPad sitting on a counter near the entrance with the feed of a camera on the lobby of the main terminal. A note placed nearby reads, “Here’s a glimpse of what you’re missing over at the main terminal right now.†It’s not enough to avoid the hoi polloi, one must take the time to sneer at them and perhaps be amused by their grubby, miserable lives.

Undoubtedly everyone who pays the annual $7,500 membership fee and the $3,000 fee per flight taken have all the right political positions and are heartbroken over Hillary’s denial to the throne. They just don’t understand how so many in those wretched places like Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan and Wisconsin could vote “against their own interests.†Nor do they understand how these horrible deplorables who look so amusing on the iPad feed struggling with their luggage on the way to crass, plastic destinations, could possibly continue to back this horrid little orange man from the crass, plastic world of real estate dealings.

Out in the hinterlands, where technology and government has abandoned them, where their God is mocked and they offer up their sons and daughters to the military and the Marxists of the academy in hopes they will find their piece of the dying American Dream, they look at what’s happening in Washington and they feel as embattled as the President. And the party they thought was on their side reveals itself to be as disconnected from them as the LAX voyeurs.

Something has to change. It’s not going to be Trump. He is what he is.

09 Apr 2017

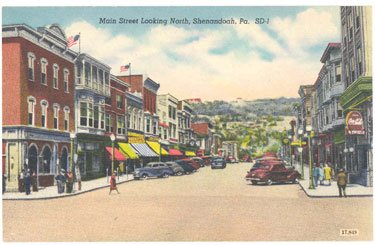

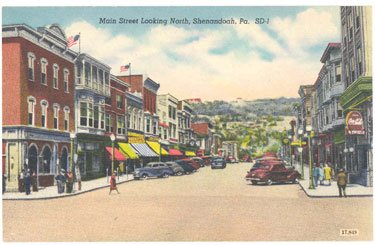

North Main Street, Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, just a bit before my time. It still looked just like this when I was a boy.

Cornell Economic historian Louis Hyman strokes his chin in the New York Times, points out to the rest of us peons the economic realities that everybody already knows, and then assures Red State Trump supporters who prefer small towns to the metropolis that they can do just fine after all.

We need merely get used to doing without buildings, streets, theaters, bars, and churches, and make ourselves comfortable in electronic neighborhoods on Internet social media, while making a good living marketing our quaint custom handicrafts to the international luxury market on-line.

Isn’t it easy to solve these things from your departmental office at Cornell?

Throughout the Rust Belt and much of rural America, the image of Main Street is one of empty storefronts and abandoned buildings interspersed with fast-food franchises, only a short drive from a Walmart.

Main Street is a place but it is also an idea. It’s small-town retail. It’s locally owned shops selling products to hardworking townspeople. It’s neighbors with dependable blue-collar jobs in auto plants and coal mines. It’s a feeling of community and of having control over your life. It’s everything, in short, that seems threatened by global capitalism and cosmopolitan elites in big cities and fancy suburbs.

Mr. Trump’s campaign slogan was “Make America Great Again,†but it could just as easily have been “Bring Main Street Back.†Since taking office, he has signed an executive order designed to revive the coal industry, promised a $1 trillion infrastructure bill and continued to express support for tariffs and to criticize globalism and international free trade. “The jobs and wealth have been stripped from our country,†he said last month, signing executive orders meant to improve the trade deficit. “We’re bringing manufacturing and jobs back.â€

But nostalgia for Main Street is misplaced — and costly. Small stores are inefficient. Local manufacturers, lacking access to economies of scale, usually are inefficient as well. To live in that kind of world is expensive.

This nostalgia, like the frustration that underlies it, has a long and instructive history. Years before deindustrialization, years before Nafta, Americans were yearning for a Main Street that never quite existed. . . . The fight to save Main Street, then as now, was less about the price of goods gained than the cost of autonomy lost. . . .

To save Main Street, state lawmakers in the 1930s passed “fair trade†legislation that set floors for retail prices, protecting small-town manufacturers and retailers from big business’s economies of scale. These laws permitted manufacturers to dictate prices for their products in a state (which is where that now-meaningless phrase “manufacturer’s suggested retail price†comes from); if a manufacturer had a price agreement with even one retailer in a state, other stores in the state could not discount that product. As a result, chain stores could no longer demand a lower price from manufacturers, despite buying in higher volumes.

These laws allowed Main Street shops to somewhat compete with chain stores, and kept prices (and profits) higher than a truly free market would have allowed. At the same time, workers, empowered by the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, organized the A. & P. and other chain stores, as well as these buttressed Main Street manufacturers, so that they also got a share of the profits. Main Street — its owners and its workers — was kept afloat, but at a cost to consumers, for whom prices remained high.

But this world was unsustainable. It unraveled in the 1960s and 1970s, as fair trade laws were repealed, manufacturers discovered overseas suppliers and unions came undone. On Main Street, prices came down for shoppers, but at the same time, so did wage growth. Main Street was officially dead.

It’s worth noting that the idealized Main Street is not a myth in some parts of America today. It exists, but only as a luxury consumer experience. Main Streets of small, independent boutiques and nonfranchised restaurants can be found in affluent college towns, in gentrified neighborhoods in Brooklyn and San Francisco, in tony suburbs — in any place where people have ample disposable income. Main Street requires shoppers who don’t really care about low prices. The dream of Main Street may be populist, but the reality is elitist. “Keep it local†campaigns are possible only when people are willing and able to pay to do so.

In hard-pressed rural communities and small towns, that isn’t an option. This is why the nostalgia for Main Street is so harmful: It raises false hopes, which when dashed fuel anger and despair. President Trump’s promises notwithstanding, there is no going back to an economic arrangement whose foundations were so shaky. In the long run, American capitalism cannot remain isolated from the global economy. To do so would be not only stultifying for Americans, but also perilous for the rest of the world’s economic growth, with all the attendant political dangers. …

Many rural Americans, sadly, don’t realize how valuable they already are or what opportunities presently exist for them. It’s true that the digital economy, centered in a few high-tech cities, has left Main Street America behind. But it does not need to be this way. Today, for the first time, thanks to the internet, small-town America can pull back money from Wall Street (and big cities more generally). Through global freelancing platforms like Upwork, for example, rural and small-town Americans can find jobs anywhere in world, using abilities and talents they already have. A receptionist can welcome office visitors in San Francisco from her home in New York’s Finger Lakes. Through an e-commerce website like Etsy, an Appalachian woodworker can create custom pieces and sell them anywhere in the world.

Americans, regardless of education or geographical location, have marketable skills in the global economy: They speak English and understand the nuances of communicating with Americans — something that cannot be easily shipped overseas. The United States remains the largest consumer market in the world, and Americans can (and some already do) sell these services abroad.

21 Mar 2017

Glenn Reynolds points out that when members of today’s establishment class of credentialed experts complain that ordinary Americans commonly reject their scientific consensus on Climate Change, their moral consensus, and their economic and policy consensus, there are reasons that the prestige and authority of the credentialed experts class have dramatically declined within the lifetimes of the Baby Boom generation.

[T]he “experts†don’t have the kind of authority that they possessed in the decade or two following World War II. Back then, the experts had given us vaccines, antibiotics, jet airplanes, nuclear power and space flight. The idea that they might really know best seemed pretty plausible.

But it also seems pretty plausible that Americans might look back on the last 50 years and say, “What have experts done for us lately?†Not only have the experts failed to deliver on the moon bases and flying cars they promised back in the day, but their track record in general is looking a lot spottier than it was in, say, 1965.

It was the experts — characterized in terms of their self-image by David Halberstam in The Best and the Brightest — who brought us the twin debacles of the Vietnam War, which we lost, and the War On Poverty, where we spent trillions and certainly didn’t win. In both cases, confident assertions by highly credentialed authorities foundered upon reality, at a dramatic cost in blood and treasure. Mostly other people’s blood and treasure.

And these are not isolated failures. The history of government nutritional advice from the 1960s to the present is an appalling one: The advice of “experts†was frequently wrong, and sometimes bought-and-paid-for by special interests, but always delivered with an air of unchallengeable certainty.

In the realm of foreign affairs, which should be of special interest to the people at Foreign Affairs, recent history has been particularly dreadful. Experts failed to foresee the fall of the Soviet Union, failed to deal especially well with that fall when it took place, and then failed to deal with the rise of Islamic terrorism that led to the 9/11 attacks. Post 9/11, experts botched the reconstruction of Iraq, then botched it again with a premature pullout.

On Syria, experts in Barack Obama’s administration produced a policy that led to countless deaths, millions of refugees flooding Europe, a new haven for Islamic terrorists, and the upending of established power relations in the mideast. In Libya, the experts urged a war, waged without the approval of Congress, to topple strongman Moammar Gadhafi, only to see — again — countless deaths, huge numbers of refugees and another haven for Islamist terror.

It was experts who brought us the housing bubble and the subprime crisis. It was experts who botched the Obamacare rollout. And, of course, the experts didn’t see Brexit coming, and seem to have responded mostly with injured pride and assaults on the intelligence of the electorate, rather than with constructive solutions.

By its fruit the tree is known, and the tree of expertise hasn’t been doing well lately. As Nassim Taleb recently observed: “With psychology papers replicating less than 40%, dietary advice reversing after 30 years of fatphobia, macroeconomic analysis working worse than astrology, the appointment of Bernanke who was less than clueless of the risks, and pharmaceutical trials replicating at best only 1/3 of the time, people are perfectly entitled to rely on their own ancestral instinct and listen to their grandmothers.â€

Then there’s the problem that, somehow, over the past half-century or so the educated classes that make up the “expert†demographic seem to have been doing pretty well, even as so many ordinary folks, in America and throughout the West, have seen their fortunes decaying. Is it any surprise that claims to authority in the form of “expertise†don’t carry the same weight that they once did?

If experts want to reclaim a position of authority, they need to make a few changes. First, they should make sure they know what they’re talking about, and they shouldn’t talk about things where their knowledge isn’t solid. Second, they should be appropriately modest in their claims of authority. And, third, they should check their egos. It doesn’t matter what your SAT scores were, voters are under no obligation to listen to you unless they find what you say persuasive.

30 Jan 2017

Acculturated:

Peter Augustine Lawler, a professor of government at Berry College, in the new edition of National Affairs. Lawler sees the Donald Trump-Hillary Clinton contest as in large part a tale of the brutish against the nice. Many a Clinton voter would enthusiastically agree. But while the dangers of brutish thinking are obvious, Lawler points out that there is also good reason for niceness to be rejected by Americans in large parts of the country.

Niceness isn’t really a virtue, Lawler says. It’s more of a cop-out, a moral shrug. “A nice person won’t fight for you,†he points out. “A nice person isn’t animated by love or honor or God. Niceness, if you think about it, is the most selfish of virtues, one, as Tocqueville noticed, rooted in a deep indifference to the well-being of others.†Trump’s lack of niceness, so horrifying to Clinton voters, registered to his acolytes as a willingness to fight for what’s good, particularly American jobs and American culture.

Niceness is paradoxically more selfish than undisguised selfishness to Lawler, because an openly selfish person at least signals to others what his intentions are. Niceness, however, means, “I let you do—and even affirm—whatever you do, because I don’t care what you do . . . Niceness, as Allan Bloom noticed, is the quality connected with flatness of soul.†Lawler goes on to remark that in an increasingly nice world, in which faking niceness becomes an important job skill, soldiers and police officers become part of the counterculture. Men, especially white men, especially working-class white men, are the ones who do the not-nice jobs in our country, are comfortable with brutishness, and see the global economy as a fierce struggle between “them†(the Chinese who are stealing our jobs, the Mexicans who are undercutting us on wages) and us.

The nice people, cocooned in wealthy coastal zip codes and doing service work that doesn’t require getting your hands dirty, don’t see any of this, but they’re happy to leave the struggling classes to their fates. For the upper echelons of society, this wasn’t always so; not long ago, in Britain for instance, the well-heeled felt a duty to lead, to provide cultural guidance. These were the aristocrats, and they ran the institutions—the church, the BBC—that were beacons for the aspirational. The bourgeoisie worked as one strongly to discourage socially destructive behavior such as raising children outside wedlock, drug or alcohol abuse, or idleness. Those who couldn’t speak proper English were encouraged to do so.

Today, in Britain as in America, the nice-ocracy simply shrugs as the struggling classes make terrible decisions. Who are we to impose our values on others, ask the nice-ocrats? Isn’t this or that regional patois just as good as standard English? If children in the poorer zip codes are getting a terrible education, the nice-ocrats don’t make a fuss. People are intelligent in their own ways, say the nice-ocrats. If testing doesn’t support this, we should cast doubt on the tests. Anyway, if the not-so-gifted people raise not-so-gifted children, there won’t be additional competition for those few spots on the best campuses. At Dartmouth, Yale and Princeton, there are more students from the top one-percent of the income scale than the bottom 60 percent. The nice-ocracy smiles and says, “Yes, but we voted for slightly higher taxes last time. Surely the poor unfortunates will see a bump in their welfare checks soon. Now excuse me, I have to take Emmett to his viola lesson and then his SAT tutor.â€

04 Oct 2016

Why did low-information, not-particularly-ideological Republican voters go loco this year, reject all the qualified and genuinely principled candidates in favor of a Reality TV clown and populist demagogue?

They were fed up and simply wanted to express their animosity toward, and contempt for, the holier-than-thou, we-know-better community of fashion elite that controls the national establishment and which, under Obama, has end run the democratic process and simply imposed its will on the larger majority it contemptuously ignores again and again.

Matthew Continetti explains that the nomination of Trump is the steam explosion that occurs when all the democratic pressure release valves on the engine of government have been sealed shut by its careless operators.

This is a moment of dissociation—of unbundling, fracture, disaggregation, dispersal. But the disconnectedness is not merely social. It is also political—a separation of the citizenry from the governments founded in their name. They are meant to have representation, to be heard, to exercise control. What they have found instead is that ostensibly democratic governments sometimes treat their populations not as citizens but as irritants.

The sole election that has had any bearing on the fate of Obamacare, for example, was the one that put Barack Obama in the White House. The special election of Scott Brown to the Senate did not stop Democratic majorities from passing the law over public disapproval. Nor did the 2010, 2012, or 2014 elections prevent or slow down the various agencies of the federal government from reorganizing the health care sector according to the latest technocratic fashions.

The last big immigration law was passed under President Clinton in an attempt to reduce illegal entry. Since then the bureaucracy has been on autopilot, admitting huge numbers to the United States and unable (and sometimes unwilling) to cope with the surge in illegal immigration at the turn of the century. In 2006, 2007, and 2013, public opinion stopped major liberalizations of immigration law. Then the president used executive power to protect certain types of illegal immigrant from deportation anyway.

Coal miners have no voice in deliberations over their futures. Only the courts stand in the way of the Clean Power Plan that will end the coal industry and devastate the Appalachian economy. Congress is unable to help. The president went over the heads of the Senate by calling his carbon deal with China an “agreement†and not a treaty.

There has been no accountability for an IRS that abused its powers to target conservative nonprofits, for Hillary Clinton who disregarded national security in the operation of her private email server, for the FBI that treated Clinton with kid gloves while not following up on individuals who became terrorists. The most recent disclosures in the attack on the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Fla., show the terrorist Omar Mateen was clearly motivated by devotion to radical Islam and to ISIS. We are only finding this out now because of a lawsuit filed by a news organization. What is the FBI afraid of?

Progressives disregard constitutional objections as outmoded artifacts of a benighted era. Who cares how Obamacare was passed or implemented, the uninsured rate is down. Why should Obama submit a treaty to the Senate when he knows it won’t be ratified; the fate of the planet is at stake. The absence of comprehensive immigration reform isn’t evidence that progressives failed to marshal a constitutional majority for passage. It’s reason for the president to test the limit of his powers. Nor does government failure result from overextension and ineptitude. It is caused by a lack of resources.

Is it really surprising that our democracy has become more tenuous as the distance between citizen and government has increased? A large portion of the electorate, it would seem, is no longer willing to tolerate a bipartisan establishment that seems more concerned with the so-called “globalist†issues of trade, migration, climate, defense of a rickety world order, and transgender rights than with the experiences of joblessness, addiction, crime, worry for one’s children, and not-so-distant memories of a better, stronger, more respected America.

These concerns are often written off as racism, or resentment, or status anxiety—as reaction, backlash, atavism, obstacles to universal progress. The same was said of McCarthy in the 1950s, the New Right in the 1970s, the Tea Party eight years ago. But in every case, including this one, the populist upsurge signified a genuine and not entirely irrational objection of a part of the electorate to its dissociation from the life of the polity.

[F]rom ..“Donald Trump and the American Crisis†by John Marini:

Those most likely to be receptive of Trump are those who believe America is in the midst of a great crisis in terms of its economy, its chaotic civil society, its political corruption, and the inability to defend any kind of tradition—or way of life derived from that tradition—because of the transformation of its culture by the intellectual elites. This sweeping cultural transformation occurred almost completely outside the political process of mobilizing public opinion and political majorities. The American people themselves did not participate or consent to the wholesale undermining of their way of life, which government and the bureaucracy helped to facilitate by undermining those institutions of civil society that were dependent upon a public defense of the old morality.

Marini refers to institutions such as the family, church, and school, institutions charged with forming the character of a citizen, of instructing him in codes of morality and service, in the traditions and history of his country, in the case of the church directing him spiritually and providing him a definitive account of the cause and purpose of life. These are precisely the institutions that have been brought under the sway of bureaucracies and courts heavily insulated from elections, from public opinion, from majority rule. And as the public has lost authority over decision-making in the private sphere, as the culture has become more alien, more bewildering, more hostile to “the old morality,†as President Clinton keeps saying rather fatuously that the fates of Kenya and Kentucky are linked, is it any wonder voters have sought out a vehicle for their disgust and opposition?

28 Sep 2016

Thomas Cole, The Course of Empire: Destruction, 1833-1836, New York Historical Society.

In Claremont Review, Angelo M. Codevilla describes how “the malfeasance of our ruling class” has transformed America and brought us to the point of this year’s disgraceful presidential election.

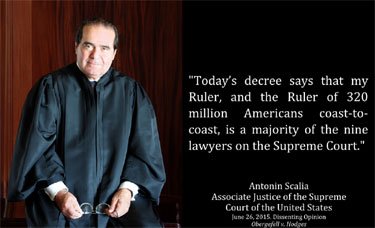

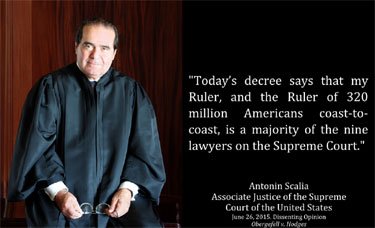

in today’s America, those in power basically do what they please. Executive orders, phone calls, and the right judge mean a lot more than laws. They even trump state referenda. Over the past half-century, presidents have ruled not by enforcing laws but increasingly through agencies that write their own rules, interpret them, and punish unaccountably—the administrative state. As for the Supreme Court, the American people have seen it invent rights where there were none—e.g., abortion—while trammeling ones that had been the republic’s spine, such as the free exercise of religion and freedom of speech. The Court taught Americans that the word “public†can mean “private†(Kelo v. City of New London), that “penalty†can mean “tax†(King v. Burwell), and that holding an opinion contrary to its own can only be due to an “irrational animus†(Obergefell v. Hodges).

What goes by the name “constitutional law†has been eclipsing the U.S. Constitution for a long time. But when the 1964 Civil Rights Act substituted a wholly open-ended mandate to oppose “discrimination†for any and all fundamental rights, it became the little law that ate the Constitution. Now, because the Act pretended that the commerce clause trumps the freedom of persons to associate or not with whomever they wish, and is being taken to mean that it trumps the free exercise of religion as well, bakers and photographers are forced to take part in homosexual weddings. A commission in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts reported that even a church may be forced to operate its bathrooms according to gender self-identification because it “could be seen as a place of public accommodation if it holds a secular event, such as a spaghetti supper, that is open to the general public.†California came very close to mandating that Catholic schools admit homosexual and transgender students or close down. The Justice Department is studying how to prosecute on-line transactions such as vacation home rental site Airbnb, Inc., that fall afoul of its evolving anti-discrimination standards. …

No one running for the GOP nomination discussed the greatest violation of popular government’s norms—never mind the Constitution—to have occurred in two hundred years, namely, the practice, agreed upon by mainstream Republicans and Democrats, of rolling all of the government’s expenditures into a single bill. This eliminates elected officials’ responsibility for any of the government’s actions, and reduces them either to approving all that the government does without reservation, or the allegedly revolutionary, disloyal act of “shutting down the government.†…

The ruling class having chosen raw power over law and persuasion, the American people reasonably concluded that raw power is the only way to counter it, and looked for candidates who would do that. Hence, even constitutional scholar Ted Cruz stopped talking about the constitutional implications of President Obama’s actions after polls told him that the public was more interested in what he would do to reverse them, niceties notwithstanding. Had Cruz become the main alternative to the Democratic Party’s dominion, the American people might have been presented with the option of reverting to the rule of law. But that did not happen. Both of the choices before us presuppose force, not law. …

In today’s America, a network of executive, judicial, bureaucratic, and social kinship channels bypasses the sovereignty of citizens. Our imperial regime, already in force, works on a simple principle: the president and the cronies who populate these channels may do whatever they like so long as the bureaucracy obeys and one third plus one of the Senate protects him from impeachment. If you are on the right side of that network, you can make up the rules as you go along, ignore or violate any number of laws, obfuscate or commit perjury about what you are doing (in the unlikely case they put you under oath), and be certain of your peers’ support. These cronies’ shared social and intellectual identity stems from the uniform education they have received in the universities. Because disdain for ordinary Americans is this ruling class’s chief feature, its members can be equally certain that all will join in celebrating each, and in demonizing their respective opponents.

And, because the ruling class blurs the distinction between public and private business, connection to that class has become the principal way of getting rich in America. Not so long ago, the way to make it here was to start a business that satisfied customers’ needs better than before. Nowadays, more businesses die each year than are started. In this century, all net additions in employment have come from the country’s 1,500 largest corporations. Rent-seeking through influence on regulations is the path to wealth. In the professions, competitive exams were the key to entry and advancement not so long ago. Now, you have to make yourself acceptable to your superiors. More important, judicial decisions and administrative practice have divided Americans into “protected classesâ€â€”possessed of special privileges and immunities—and everybody else. Equality before the law and equality of opportunity are memories. Co-option is the path to power. Ever wonder why the quality of our leaders has been declining with each successive generation?

A must read.

17 Sep 2016

Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, The Experts, 1837, National Museum Warsaw.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb inveighs against the pseudo-intelligentsia whose excesses in America have resulted in the Trumpkin Jacquerrie.

What we have been seeing worldwide, from India to the UK to the US, is the rebellion against the inner circle of no-skin-in-the-game policymaking “clerks†and journalists-insiders, that class of paternalistic semi-intellectual experts with some Ivy league, Oxford-Cambridge, or similar label-driven education who are telling the rest of us 1) what to do, 2) what to eat, 3) how to speak, 4) how to think… and 5) who to vote for. …

The Intellectual Yet Idiot is a production of modernity hence has been accelerating since the mid twentieth century, to reach its local supremum today, along with the broad category of people without skin-in-the-game who have been invading many walks of life. Why? Simply, in many countries, the government’s role is ten times what it was a century ago (expressed in percentage of GDP). The IYI seems ubiquitous in our lives but is still a small minority and rarely seen outside specialized outlets, social media, and universities — most people have proper jobs and there are not many opening for the IYI.

Beware the semi-erudite who thinks he is an erudite.

The IYI pathologizes others for doing things he doesn’t understand without ever realizing it is his understanding that may be limited. He thinks people should act according to their best interests and he knows their interests, particularly if they are “red necks†or English non-crisp-vowel class who voted for Brexit. When Plebeians do something that makes sense to them, but not to him, the IYI uses the term “uneducatedâ€. What we generally call participation in the political process, he calls by two distinct designations: “democracy†when it fits the IYI, and “populism†when the plebeians dare voting in a way that contradicts his preferences.

Read the whole thing.

01 Aug 2016

St. Paul’s

What with the rebellion of the low-information voter and the ascent of Donald Trump, the white working class is in the news a lot these days and everyone is reading J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy (previously mentioned here), a personal eulogy from an upwardly-mobile ex-Marine to his rust-bucket hometown and left-behind family and friends.

The perfect counterpoint book to read, I think, is Shamus Rahman Khan’s Privilege: The Making of an Adolescent Elite at St. Paul’s School.

J.D. Vance describes how History and Culture have failed our society’s losers.

Shamus Rahman Khan describes, with a mixture of astonishment and congratulatory applause, just how one of the absolutely snobbiest and most expensive secondary boarding schools in America (the place that educated John Kerry and Doonesbury’s Gary Trudeau) educates future winners in a combination of graceful personal ease, the ability to fake your way through anything you don’t actually know, and a nihilistic belief in the complete equality of all things (excluding only your own special elite status).

St. Paul’s often touts its academic program as the best in the nation. In its advertising literature, the school boasts that it has “the highest level of scholarship” and that its “students stand at the top of their peer group in terms of academic preparation.” And according to eager administrators and lackadaisical adolescents alike, the centerpiece of St. Paul’s academic program is undoubtedly the humanities. The humanities program introduces students to the history, literature, and thoughts of different moments in world history. The humanities division describes in some project is an interdisciplinary, multi-vocal investigation of “great questions.” …

This program, significantly, does not teach students to know “things.” The emphasis is not on memorizing historical events, for example. Instead it is on cultivating “habits of mind,” which encourage a particular way of relating both to the world and to each other. …

The enormity of this program is both thrilling and terrifying. The thought of knowing all of that, being swept up and carried through the tide of history, is tantalizing. It is also the product of St. Paul’s hubris. How can any one person possibly teach everything..? As I prepared to teach my own class at the school, I soon found out that I was asking the wrong question. Of course the expectations were ridiculous. No high schooler could ever learn all that the course offers. The more important question, I eventually realized, is much harder to answer: what this mean to present material in this way to teenagers?

Perhaps the point is not really to know anything. The advantage the St. Paul’s installs instills in its students is not a hierarchy of knowledge. As we have seen, knowledge is no longer the exclusive domain of the elite. And these days, information flows so freely that to use it to exclude others is increasingly challenging. By contrast, the important decisions required for those who lead are not based on knowing more but instead are founded in habits of mind. St. Paul’s teaches that everything can be accomplished through these habits, even while still in high school. What strikes me as presumptuous, even shocking, about this vision of the world is taken for granted by pretty much every teenager at St. Paul’s.

Though I marveled at how impossible it seemed to teach students all these things, the school itself seems largely unconcerned about this. Indeed, St. Paul’s approach seems closer to Plato’s outline of education in Republic. Building upon his famous cave metaphor, Plato tells us, “Education isn’t what some people declare it to be, namely putting knowledge of the souls that lack it, like putting sight into blind eyes …” ..In short, education is not teaching students things they don’t know. Rather it is teaching them to think their way through the world. …

“I don’t actually know much,” an alumnus told me after he finished his freshman year at Harvard. “I mean, well, I don’t know how to put it. When I’m in classes all these kids next to me know a lot more than I do. Like about what actually happened in the Civil War. Or what France did in World War II. I don’t know any of that stuff. But I know something they don’t. It’s not facts or anything. It’s how to think. That’s what I learned in humanities.”

“What do you mean how to think?” I asked.

“I mean I learned how to think bigger. Like everyone else at Harvard knew about the Civil War. I didn’t. But I knew how to make sense of what they knew about the Civil War and apply it. So they knew a lot about particular things. I knew how to think about everything.”

The emphasis of the St. Paul’s curriculum is not on “what you know” but on “how you know it.” Teaching ways of knowing rather than teaching the facts themselves, St. Paul’s is able to endow its students with marks of the elite –ways of thinking or relating to the world– that ultimately help make up privilege. As the exclusionary practices of old the become unsustainable, something new has emerged from within the elite. …

[S]tudents learn to consume from an enormous variety of sources. They learn to work and “interact” with art, literature, history, from the popular to the scholarly, and have a huge range of materials their disposal. For example, one of the major assignments in Humanities III is to compare “Beowulf” to Steven Spielberg’s “Jaws.” Students are asked to think about the ways in which Beowulf is a monster [Beowulf is the hero. Grendel is the monster. –JDZ] that man must confront, just as “Jaws”‘s monster prowls the waters of humanity (and perhaps even our own internal waters [And the BS keeps on flowing. –JDZ]). The goal is not to endow the students with a kind of highbrow elite knowledge. Rather, they are taught to move with ease to the broad range of culture, to move with felicity from the elite to the popular. They learn to be cultural egalitarians. The lesson to students is that you can talk about “Jaws” in the same way you can talk about “Beowulf.” Both become cultural resources to draw upon. And most important, the world is available to you –from high literature to horror films. They’re not things that are “off-limits” –limits are not structured by the relations of the world around you; they are in you. Students are not to stand above the mundane, perhaps lowbrow horror flick. Instead they are taught the importance of engaging with all aspects of culture, of treating the high and low with respect and serious engagement. As our future elite, the students are taught not to create fences and moats but instead to relentlessly engage with the varied world around them.

The consequences of St. Paul’s philosophy can be seen all over campus, evident even in how students carry themselves. Students have the sense that they could do it. The world is a space to be navigated and renegotiated, not a set of arrangements or a list of rules that are imposed upon you. The students are taught that they are special, and they begin to realize this specialness. This is a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy –thinking everything is possible just might make it so.

25 Jul 2016

Michael Ginsberg is fed up with experts trained neither in facts or real skills, but in the Humanities-style “How to Think in General” kind of elite education.

I trained to be an engineer in college and graduate school. When I went to college, I viewed it as job training. School had a purpose, and I had a mission: prepare myself for the working world by developing skills and a vocation. It was hard work: hours upon hours in labs, in libraries working on problem sets, or studying in my dorm room. It wasn’t easy, but I kept going because I believed engineering was one of the most essential disciplines to Americans’ quality of life and the defense of the nation.

Yet throughout my time in school, it always gnawed at me that my fellow classmates in other disciplines—the students of government, political science, and policy, masters of words, theories, and rules—were going to graduate, occupy positions of power, and determine how I would be able to live my life and run my career. Never mind that many of them started their weekends on Thursdays and probably never took a class in the hard sciences while I was sweating away night and day in the engineering library. They were going to grow up and make decisions that would control my life.

I went to an Ivy League school, and the piece of parchment with the school name was going to open the doors to the gilded life that would allow them to, as one of my schoolmates put it, “rule the world.†Use the school name to get the right internships and make the right connections, and the world would open up for them. (Instead, I repeatedly had job interviewers tell me, “I didn’t know your Ivy League school had engineering.â€) I resented it deeply.

That resentment dissipated over time, but never quite went away. …

My resentment, long in remission, came back and crystallized in the following thought: Americans are governed by politicians who see fit to reimagine entire sectors of our economy and, indeed, our lives despite having little, if any, experience in the areas of life they seek to reform wholesale. This means Americans, seeing the failures of government from Obamacare to the Veterans Affairs, from the Environmental Protection Agency dumping toxic materials into a Colorado river to the Dodd-Frank regulations strangling local community banks, have had just about enough of their credentialed but utterly inexperienced supposed betters reordering their lives and livelihoods.

Read the whole thing.

Hat tip to the News Junkie.

15 Jul 2016

This is the Meritocracy?

Helen Andrews casts a jaundiced look at The New Ruling Class in Hedgehog Review.

Meritocracy began by destroying an aristocracy; it has ended in creating a new one. …

Not since the Society of the Cincinnati has a ruling elite so vehemently disclaimed any resemblance to an aristocracy. The structure of the economy abets the elite in its delusion, since even the very rich are now more likely to earn their money from employment than from capital, and thus find it easier to think of themselves basically as working stiffs. As cultural consumers they are careful to look down their noses at nothing except country music. All manner of low-class fare—rap, telenovelas, Waffle House—is embraced by what Shamus Rahman Khan calls the “omnivorous pluralism†of our elite. “It is as if the new elite are saying, ‘Look! We are not some exclusive club. If anything, we are the most democratized of all groups.’â€

Khan’s Privilege: The Making of an Adolescent Elite at St. Paul’s School is a fascinating document, because he seems to have been genuinely surprised by what he found when he returned to his old boarding school to teach for a year. Khan, the grandson of Irish and Pakistani peasants, worked his way to a Columbia University professorship in sociology via St. Paul’s and Haverford College. So he thought he knew meritocrats—but today’s breed gave him a bit of a fright. For one thing, they proved to be excellent haters. Consider how they talk about a legacy student whose background can be inferred from the pseudonym Khan gives him, “Chase Abbottâ€:

After seeing me chatting with Chase, a boy I was close with, Peter, expressed what many others would time and again: “that guy would never be here if it weren’t for his family.… I don’t get why the school still does that. He doesn’t bring anything to this place.†Peter seemed annoyed with me for even talking with Chase. Knowing that I was at St. Paul’s to make sense of the school, Peter made sure to point out to me that Chase didn’t really belong there.… Faculty, too, openly lamented the presence of students like Chase.

“Openly lamentedâ€! Poor Chase. This hatred is out of all proportion to the power still held by the Chases of the school, which is almost nil. Khan discovers that the few legacy WASPs live together in a sequestered dorm, just like the “minority dorm†of his own schooldays, and even the alumni “point to students like Chase as examples of what is wrong about St. Paul’s.†No, the hatred of students like Chase feels more like the resentment born of having noticed an unwelcome resemblance. It is somehow unsurprising to learn that Peter’s parents met at Harvard.

Of course, Peter is not at St. Paul’s because his parents went to Harvard; as he makes clear to Khan, he is there because of his hard work and academic achievement. Here we have the meritocratic delusion most in need of smashing: the notion that the people who make up our elite are especially smart. They are not—and I do not mean that in the feel-good democratic sense that we are all smart in our own ways, the homely-wise farmer no less than the scholar. I mean that the majority of meritocrats are, on their own chosen scale of intelligence, pretty dumb. Grade inflation first hit the Ivies in the late 1960s for a reason. Yale professor David Gelernter has noticed it in his students: “My students today are…so ignorant that it’s hard to accept how ignorant they are.… [I]t’s very hard to grasp that the person you’re talking to, who is bright, articulate, advisable, interested, and doesn’t know who Beethoven is. Had no view looking back at the history of the twentieth century—just sees a fog. A blank.†Camille Paglia once assigned the spiritual “Go Down, Moses†to an English seminar, only to discover to her horror that “of a class of twenty-five students, only two seemed to recognize the name ‘Moses’.… They did not know who he was.â€

Hat tip to The Barrister.

21 May 2015

John Nolte explains how David Letterman responded to losing to Jay Leno by becoming a toady to the urban establishment.

I didn’t leave David Letterman, David Letterman left me.

It was sometime around 2003 when I began to realize Letterman didn’t like me anymore. His anger was no longer subversive and clever, it was bitter and mean-spirited and palpably real. He was a jerk playing to his loyal audience — urban, cynical, elite, Blue State jerks. The humble, self-deprecating Dave had become the nasty, arrogant Letterman, an unrecognizable bully who reveled in pulling the wings off those he saw as something less.

Chris Christie’s weight; Rush Limbaugh’s personal life; everything Bill O’Reilly; Bush, Cheney, Palin, and the last straw, a statutory rape joke about Palin’s 15 year-old daughter. Suddenly you were a dangerous idiot for protecting the most Indiana of things — your gun.

The man who could make you laugh at yourself now wanted to hurt and humiliate.

Letterman’s politics were never the issue. You can’t share my passion for show business and movies and let politics get in the way. Carlin was probably to the left of Letterman, but Carlin was funny and thoughtful and smart. Watching Letterman berate and hector and attempt to humiliate conservative guests over guns and the climate and the brilliance of Obama was boorish. Describing Mitt Romney as a “felon†was just sad.

The American Heartland had disappointed its own Indiana son, and for more than a decade the son was out for payback.

Or maybe Letterman was just so scared and insecure about losing what little audience he had, that he sold out his genius and Midwestern decency to bitterly cling to them? He certainly never again displayed the courage to challenge them, or to make them feel in any way uncomfortable.

Night after night the man who became my hero for biting the hand was now licking the boot — and convinced while doing so that he’s superior to the rest of us.

How I pity him.

Read the whole thing.

/div>

Feeds

|