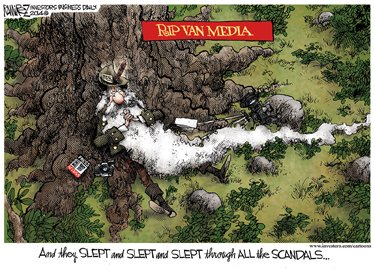

And the Winner Is…

Left Think, Progressivism, Ressentiment, Transgender Movement

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Napoleon I on his Imperial Throne, 1806, Musée de l’Armée.

My personal nominee in the most-bat-shit-crazy-Progressive-editorial-of-all-times sweepstakes is Christin Scarlett Milloy’s “Don’t Let the Doctor Do This to Your Newborn” in the current Slate.

Imagine you are in recovery from labor, lying in bed, holding your infant. In your arms you cradle a stunningly beautiful, perfect little being. Completely innocent and totally vulnerable, your baby is entirely dependent on you to make all the choices that will define their life for many years to come. They are wholly unaware (at least, for now) that you would do anything and everything in your power to protect them from harm and keep them safe. You are calm, at peace.

Suddenly, the doctor comes in. He looks at you sternly, gloved hands reaching for your baby insistently. “It’s time for your child’s treatment,†he explains from beneath a white breathing mask, shattering your calm. Clutching your baby protectively, you eye the doctor with suspicion.

You ask him what it’s for.

“Oh, just standard practice. It will help him or her be recognized and get along more easily with others who’ve already received the same treatment. The chance of side effects is extremely small.†This raises the hairs on the back of your neck, and your protective instinct kicks your alarm response up a notch. …

t’s a strange hypothetical scenario to imagine. Pressure to accept a medical treatment, no tangible proof of its necessity, its only benefits conferred by the fact that everyone else already has it, and coming at a terrible expense to those 1 or 2 percent who have a bad reaction. It seems unlikely that doctors, hospitals, parents, or society in general would tolerate a standard practice like this.

Except they already do. The imaginary treatment I described above is real. Obstetricians, doctors, and midwives commit this procedure on infants every single day, in every single country. In reality, this treatment is performed almost universally without even asking for the parents’ consent, making this practice all the more insidious. It’s called infant gender assignment: When the doctor holds your child up to the harsh light of the delivery room, looks between its legs, and declares his opinion: It’s a boy or a girl, based on nothing more than a cursory assessment of your offspring’s genitals.

We tell our children, “You can be anything you want to be.†We say, “A girl can be a doctor, a boy can be a nurse,†but why in the first place must this person be a boy and that person be a girl? Your infant is an infant. Your baby knows nothing of dresses and ties, of makeup and aftershave, of the contemporary social implications of pink and blue. As a newborn, your child’s potential is limitless. The world is full of possibilities that every person deserves to be able to explore freely, receiving equal respect and human dignity while maximizing happiness through individual expression.

With infant gender assignment, in a single moment your baby’s life is instantly and brutally reduced from such infinite potentials down to one concrete set of expectations and stereotypes, and any behavioral deviation from that will be severely punished—both intentionally through bigotry, and unintentionally through ignorance. That doctor (and the power structure behind him) plays a pivotal role in imposing those limits on helpless infants, without their consent, and without your informed consent as a parent. This issue deserves serious consideration by every parent, because no matter what gender identity your child ultimately adopts, infant gender assignment has effects that will last through their whole life.

Read the whole thing.

———————-

In the post-Christian Left’s topsy-turvy philosophic world of inverted values, the madman-with-a-sob-story, the outcast traditionally looked upon with contempt and consequently filled with ressentiment must be treated as the representative of the worthiest of causes, and his ravings and absurdities taken seriously.

In the above piece, we are told that mere recognition of actual physical reality, identifying an infant as a boy or a girl, is really a species of traditional societal oppression, which assigns identity and limits possibility at “terrible expense” to some percentage of unwilling victims.

“You can be anything you want to be,” Mr. Milloy (who is a male pretending to be a female himself) contends is the way it ought to be. But why limit the human infant’s choices to boy or girl (or LGBTQ)? Isn’t the system also limiting possibility and potentially thwarting the happiness and self-realization of some small percentage by defining the infant as being the offspring of Mr. & Mrs. Jones and a mere ordinary citizen and member of the Jones family. What about the case of the minority individual whose inner being rejects such pedestrian mediocrity and feels, deep down inside, that he is really the Emperor Napoleon?

Can it possibly be fair or just to impose conventional stereotypes and concrete expectations and deny Jones Minor his desired Imperial titles and regiment of Guards Cavalry? If personal whim is sufficient to deny the physical reality of the sexual organs you are born with, if you can reject that kind of unchosen, externally-imposed role and select a different one at will, why shouldn’t you also be entitled to reject every other decree of fate as well?

If a boy is entitled to redefine himself as a girl (and vice versa), shouldn’t short people be able to demand to be treated as tall, and to have access to height-reassignment surgery? Shouldn’t unpleasant and unattractive people be permitted to demand popularity? And why should anyone be forced by the power structure to be born in poverty and obscurity? Surely, if everyone is entitled to be anything he wants to be, we are all going to demand to be made rich and famous, if Nature neglected to arrange our birth appropriately.

Why, one wonders, limit the protean possibilities to gender. If you can reject gender assignment at birth, why not species assignment? Some people would probably prefer to be lions or wolves or dolphins.

Oops!

Black Humor, Gaffes, Hiroshima, William Hague

From IainMcintosh via Amy Alkon [FB].

Mixed Media Sculptor Christina Bothwell

Art, Christina Bothwell, Glass

Christina Bothwell, Deer sculpture in glass and ceramic

[M]ixed media sculptor Christina Bothwell: Taking aesthetic inspiration from vintage toys and dolls, antique medical illustrations and old machinery, her work embodies a sense of the nostalgic entwined with that ineffable emotion of wonder. With their colorful glass bodies, delicately modeled limbs and faces, hidden layers and surreal appendages, Bothwell’s imaginative figures seem like they were plucked from some forgotten fairy tale (one which I am desperate to read).

There is an enchanting quality about her work which I can’t quite articulate, but I think at least part of it stems from her use of the translucent glass to explore the co-existence of the inner and outer workings of the body. The glass allows a soft light to radiate through the figure and reveal hidden treasures and imperfections within, but its material vulnerability also mirrors the vulnerability of the figures she depicts: little girls, infants, and small animals. A little bit magical and a little bit menacing, Bothwell’s intriguing sculptures invite the viewer to imagine their own narrative for her figures and to delight in their visual curiosity.

——————————————

Irene Hardwick Olivieri interview

——————————————

Interview in Glass Quarterly

——————————————-

——————————————

Obsoleteinc examples for sale

——————————————

Hat tip to Madame Scherzo.

Borges Hated Soccer

Fascism, Games Versus Sport, Jorge Luis Borges, Mass Culture, Nationalism, Soccer

Shaj Matthew, in the New Republic, explains why one of the last century’s greatest writers justly despised his own country’s national obsession.

Soccer is popular,†Jorge Luis Borges observed, “because stupidity is popular.â€

At first glance, the Argentine writer’s animus toward “the beautiful game” seems to reflect the attitude of today’s typical soccer hater, whose lazy gibes have almost become a refrain by now: Soccer is boring. There are too many tie scores. I can’t stand the fake injuries.

And it’s true: Borges did call soccer “aesthetically ugly.†He did say, “Soccer is one of England’s biggest crimes.†And apparently, he even scheduled one of his lectures so that it would intentionally conflict with Argentina’s first game of the 1978 World Cup. But Borges’ distaste for the sport stemmed from something far more troubling than aesthetics. His problem was with soccer fan culture, which he linked to the kind of blind popular support that propped up the leaders of the twentieth century’s most horrifying political movements. In his lifetime, he saw elements of fascism, Peronism, and even anti-Semitism emerge in the Argentinean political sphere, so his intense suspicion of popular political movements and mass culture—the apogee of which, in Argentina, is soccer—makes a lot of sense. (“There is an idea of supremacy, of power, [in soccer] that seems horrible to me,†he once wrote.) Borges opposed dogmatism in any shape or form, so he was naturally suspicious of his countrymen’s unqualified devotion to any doctrine or religion—even to their dear albiceleste.

Soccer is inextricably tied to nationalism, another one of Borges’ objections to the sport. “Nationalism only allows for affirmations, and every doctrine that discards doubt, negation, is a form of fanaticism and stupidity,†he said. National teams generate nationalistic fervor, creating the possibility for an unscrupulous government to use a star player as a mouthpiece to legitimize itself. In fact, that’s precisely what happened with one of the greatest players ever: Pelé. “Even as his government rounded up political dissidents, it also produced a giant poster of Pelé straining to head the ball through the goal, accompanied by the slogan Ninguém mais segura este paÃs: Nobody can stop this country now,†writes Dave Zirin in his new book, Brazil’s Dance with the Devil. Governments, such as the Brazilian military dictatorship that Pelé played under, can take advantage of the bond that fans share with their national teams to drum up popular support, and this is what Borges feared—and resented—about the sport.

Read the whole thing.

Hat tip to the Dish.

Borges, of course, was perfectly right.

Soccer is just the most popular commercial team game in the world outside the United States. All commercial team games are modern developments organized originally by carnival impresarios to separate the urban proletarian from his beer nickel. These teams and the games they play are totally and completely meaningless spectacles performed purely for commercial purposes. The teams’ regional identifications and mascots are utterly meaningless. Players come from anywhere. Teams may be sold and relocated, coaches and recognizable styles of play & performance may be routinely altered on the basis of owners’ whims at the any moment.

Commercial game teams stand for absolutely nothing, and fan identification and loyalty is, as Borges recognized, a kind of willful stupidity constituting an intentional surrender of self to a totally ersatz sort of group identity.

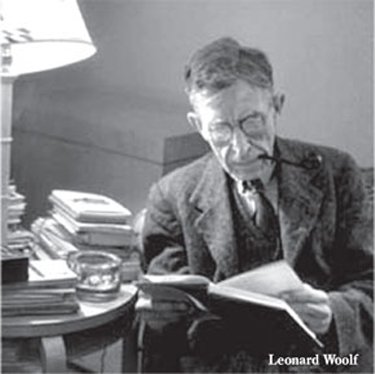

Lev Grossman: On Modernism & Modern Fantasy

J.R.R. Tolkien, Leonard Woolf, Lev Grossman, Modern Fantasy, Modernism

In his 2010 essay, “The Death of a Civil Servant,” fantasy novelist Lev Grossman finds the collision between Modernism and the Revulsion Against Modernism Expressed as Fantasy exemplified in the 1905 colonial experiences of Bloomsbury’s Leonard Woolf.

All Englishmen who were in their twenties in 1905 had at least one thing in common: They’d watched the world of their childhoods die. Just as they were coming of age, electricity replaced gaslight. Cars and buses replaced horses and bicycles. Urban populations were exploding, mass media and advertising were yammering, and mechanized warfare crouched in the wings, ready and waiting. The early twentieth century looked and sounded and smelled nothing like the late nineteenth. “In those days of the eighties and nineties of the nineteenth century the rhythm of London traffic which one listened to as one fell asleep in one’s nursery was the rhythm of horses’ hooves clopclopping down London streets in broughams, hansom cabs, and four-wheelers,†Woolf would write, toward the end of his life, in the unimaginable year of 1960. “And the rhythm, the tempo got into one’s blood and one’s brain, so that in a sense I have never become entirely reconciled in London to the rhythm and tempo of the whizzing and rushing cars.†Woolf felt displaced, like the hero of H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine, exiled in the future. So did everybody else—Evelyn Waugh once remarked that if he ever got ahold of a time machine, he’d put it in reverse and go backward, into the past.

It’s no accident that both modernism and modern fantasy made their entrances at that moment, in that same displaced generation. It’s rarely remarked upon, but just as Virginia Woolf and Joyce and Hemingway were inventing the modernist novel, Hope Mirrlees and Lord Dunsany and Eric Rücker Eddison were writing the first modern fantasy novels, at least in the form most fans are familiar with. This happened for a reason. Modernism and fantasy were two very different responses to the same disaster: the arrival of the modern era and the death of Woolf’s beloved nursery-world. Though like siblings—or roommates—who are mortally embarrassed by each other, they’re not in the habit of acknowledging the connection. …

But fantasy and modernism aren’t just opposites, they’re mirror images of each other. When the social, cultural, and technological catastrophe that inaugurated the twentieth century took place, leaving the neat, coherent Victorian universe a desecrated ruin, all that was left for writers to do was to sift disconsolately through the rubble and dream of the organic, vital world that had once been. Modernism was pieced together out of the jagged shards of that shattered world—it’s a literature made of fragments, the better to resemble the carnage it represented. Whereas fantasy was a vision of that lost, longed-for world itself, a dream of a medieval England that never was: green, whole, prelapsarian, magical.

Here and there you can spot their shared heritage, the places where modernism and fantasy touch. Modernists and fantasists both rework myths and legends: you can watch King Arthur and his knights trot, obscured but still visible, through Eliot’s “The Waste Land,†Virginia Woolf’s The Waves (in the person of the knightly Percival), and Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (“Arser of the Rum Tippleâ€) to emerge into the sunlit meadows of T. H. White’s The Once and Future King. Modernism and fantasy are set against the same landscapes: verdant preindustrial hills and dark, broken ruins. La tour abolie of “The Waste Land†is the architectural double of Orthanc, the tower of Saruman the White in The Lord of the Rings. The green fields of Narnia abut the “fresh green breast of the new world†that Fitzgerald invokes at the end of The Great Gatsby.

But by the time we reach them, those green fields are always in decline. The spell never lasts. King Arthur is always dying, and the Elves are always shuffling off toward Valinor, where mortals cannot follow. Narnia falls into chaos, then drowns and freezes, and the survivors retreat into Aslan’s Land. We think of fantasy and modernism as worlds apart, but somehow they always end up in the same place. They are perfectly symmetrical. Fantasy is a prelude to the apocalypse. Modernism is the epilogue.

Read the whole thing.

Via Ratak Monodosico.

Warner Bwothers’ Wascals Were Wefties!

Bugs Bunny, Gay Marriage, James Lileks, Satire, Warner Brothers Cartoons

James Lileks defends the classic Warner brothers cartoons against an attack in (now wanting to charge you money) STALE magazine by LGBTQ-expert Mark Joseph Stern bemoaning how brutal the old cartoons were and finding their comedic violence “appallingly macabre” by noting just how ahead-of-their-time Bugs, Elmer, Daffy and the rest were in championing self-construction of identity and same-sex marriage.

Slate came up with a piece called “Looney Tunes cartoons were more brutal than you remember,â€* which concludes:

But no kids’ show today would ever treat firearms or gun deaths so lightly, with such zany exuberance, as Looney Tunes once did. That jaunty disregard of the consequences of violence is part of what made the show so bizarrely delightful. In a post-Newtown world, however, what was once strangely funny now registers as appallingly macabre.

Yes —- if you’ve had your sense of humor surgically removed, and replaced with an oversized gland that produces chemicals responsible for compulsive frowning. Otherwise you might continue to find them strangely funny, oddly funny, audaciously funny, or perhaps just hilarious. There are still some, I hope, who can smile at the sight of Daffy’s beak blown clear around to the other side of his head after Fudd loosed a blunderbuss blast. There is no pain involved; only irritation and annoyance. He readjusts his beak with an audible squeaking sound, and stomps off to yell at Bugs, instigator of the incident.

But that very episode — “Duck! Rabbit, Duck!†— contains messages that should hearten the heart of a Slate writer, for it contains a very modern message about identity. As you may recall, the plot concerns Fudd’s confusion over which season it is: Wabbit, or Duck? The signage is confusing. Daffy self-identifies as a duck, and this being the ’40s, he is locked in a fixed identity, a product of a culture that says if it walks like a duck and talks like a duck it is a duck. But as we now know, “species†is as fluid as any other form of identity.

And that’s something Bugs reveals in a very subversive sequence. Daffy uses colloquial expressions to describe his mood, noting that he feels like a goat. Whereupon Bugs produces a sign that says it is Goat Season. Fudd unloads accordingly. It may look like violence. But it’s really acceptance. If Daffy says he is a goat then he is a goat. He may suffer the consequences, but Fudd has affirmed his statement of identity. Over the course of the cartoon Daffy identifies with various species, and in each instance Bugs has an appropriate placard to nudge Fudd toward accepting the fluid spectrum on which Daffy may choose to locate himself.

Half a century before Facebook’s 57 genders, Warner Brothers was laying the groundwork.

It’s not an isolated example of progressive themes in Looney Tunes. “Hillbilly Hare†contains a wealth of sociological insight. The main characters are two rural archetypes mired in poverty, wandering the backwoods shoeless, engaged in a pointless blood feud. You could almost call it “What’s the Matter with the Ozarks,†for instead of concentrating their enmity against the 1 percent that has exploited their labor and resources, they are pitted against each other in a pointless struggle.

Into this world comes Bugs, who draws their attention by dressing up as a seductive female rabbit — a transgressive statement that manages to lampoon heteronormative behavior (transgender Bugs feigns interest in the males) and reinforces the worst sort of cross-dressing stereotypes, as female-identified Bugs is all lipstick and hip-cocking sashay exaggeration. But for the time it was groundbreaking. To a youth who sat in the theater in 1948 it may have said, Yes, it is possible to break the confines of biological gender, and to do so with such confidence and style that people who would otherwise fricassee you for supper would follow your every suggestion.

And what a suggestion! In a hilarious set piece, Bugs calls a square-dance tune whose instructions aren’t the usual do-si-do, bow-to-your-left, but consist entirely of commands to inflict escalating levels of retributive violence. The men, socially and culturally conditioned to follow any command the square-dance caller makes, are not only helpless to assert their own will, they end up dancing with each other. This redefines the courtship ritual of the dance — a means of channeling and controlling sexual energy — into a fiercely homoerotic ballet.

“Hit ’im again, the critter ain’t dead.†It’s safe to assume Bugs is talking about the stifling hand of religious intolerance and centuries of marriage inequality. With a tidy couplet he brushes away the pope’s objections: Promenade like a bride and groom, he calls, and that they do. …

Bugs would return to the idea of same-sex marriage in one of the most popular and enduring cartoons, the one based on the “Barber of Seville.†While most of the cartoon involves the usual violence — much of which seems macabre and inappropriate in light of the fact that someone could be murdered at La Scala, some day — it ends with the whirlwind courtship of Bugs and Fudd. They point guns of increasing size at each other, a metaphor for the escalating divisions of contemporary politics — but Bugs utterly defuses the situation by presenting Fudd with flowers, and Elmer promptly changes into a wedding dress.

If ever there was a marvelous rendition of the swiftness with which the debate on marriage equality changed, it’s that. Granted, Bugs picks up Elmer and drops him from a great height, but the course of true love never did run smoothly.

Read the whole thing.

——————————

——————————

Minneapolis, Minnesota National Cemetery

Omens and Symbols, Photography

Photo: Minneapolis Star/Tribune

Via Gwynnie.