Category Archive 'New Yorker'

25 May 2022

Bird Dog, on Maggie’s Farm, linked Roger Angell’s New Yorker 2002 tribute to the greatest of all cocktails, the Martini.

The Martini is in, the Martini is back—or so young friends assure me. At Angelo and Maxie’s, on Park Avenue South, a thirtyish man with backswept Gordon Gekko hair lowers his cell as the bartender comes by and says, “Eddie, gimme a Bombay Sapphire, up.” At Patroon, a possibly married couple want two dirty Tanquerays—gin Martinis straight up, with the bits and leavings of a bottle of olives stirred in. At Nobu, a date begins with a saketini—a sake Martini with (avert your eyes) a sliver of cucumber on top. At Lotus, at the Merc Bar, and all over town, extremely thin young women hold their stemmed cocktail glasses at a little distance from their chests and avidly watch the shining oil twisted out of a strip of lemon peel spread across the pale surface of their gin or vodka Martini like a gas stain from an idling outboard. They are thinking Myrna Loy, they are thinking Nora Charles and Ava Gardner, and they are keeping their secret, which is that it was the chic shape of the glass—the slim narcissus stalk rising to a 1939 World’s Fair triangle above—that drew them to this drink. Before their first Martini ever, they saw themselves here with an icy Mart in one hand, sitting on a barstool, one leg crossed over the other, in a bar small enough so that a cigarette can be legally held in the other, and a curl of smoke rising above the murmurous conversation and the laughter. Heaven. The drink itself was a bit of a problem—that stark medicinal bite—but mercifully you can get a little help for that now with a splash of scarlet cranberry juice thrown in, or with a pink-grapefruit-cassis Martini, or a green-apple Martini, or a flat-out chocolate Martini, which makes you feel like a grownup twelve years old. All they are worried about—the tiniest dash of anxiety—is that this prettily tinted drink might allow someone to look at them and see Martha Stewart. Or that they’re drinking a variation on the Cosmopolitan, that Sarah Jessica Parker–“Sex and the City” craze that is so not in anymore.

Not to worry. In time, I think, these young topers will find their way back to the Martini, to the delectable real thing, and become more fashionable than they ever imagined. In the summer of 1939, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited President Franklin Delano Roosevelt at Hyde Park—it was a few weeks before the Second World War began—and as twilight fell F.D.R. said, “My mother does not approve of cocktails and thinks you should have a cup of tea.” The King said, “Neither does my mother.” Then they had a couple of rounds of Martinis.

I myself might have had a Martini that same evening, at my mother and stepfather’s house in Maine, though at eighteen—almost nineteen—I was still young enough to prefer something sweeter, like the yummy, Cointreau-laced Sidecar. The Martini meant more, I knew that much, and soon thereafter, at college, I could order one or mix one with aplomb. As Ogden Nash put it, in “A Drink with Something in It”:

There is something about a Martini,

A tingle remarkably pleasant;

A yellow, a mellow Martini;

I wish I had one at present.

There is something about a Martini

Ere the dining and dancing begin,

And to tell you the truth,

It is not the vermouth—

I think that perhaps it’s the gin.

RTWT

He failed to include Dorothy Parker’s poem:

“I like to have a martini,

Two at the very most.

After three I’m under the table,

after four I’m under my host.”

19 May 2022

Larry Tribe.

Isaac Chotiner interviews the Left’s favorite law professor, Larry Tribe, for the New Yorker, seeking his response to the lamentable circumstance of the country finding itself with a conservative, Originalist majority on Supreme Court, an apparent majority perfectly prepared to reverse Roe v. wade.

Larry is obviously not happy.

How has your thinking about the Supreme Court as an institution changed over the past fifty years?

I would say that because I am part of the generation that grew up in the glow of Brown v. Board of Education and of the Warren and Brennan Court, and identified the Court really with making representative government work better through the reapportionment decisions and protecting minorities of various kinds. I saw the Court through rather rose-tinted glasses for a while. As I taught the Court for decades, I came to spend more time on the dark periods of the Court’s history, thinking about how the Court really preserved and protected corporate power and wealth more than it protected minorities through much of our history, and how it essentially gutted the efforts at Reconstruction, and I focussed more on cases like Dred Scott and Plessy v. Ferguson and Korematsu.

And in recent years, as the Court has turned back to its characteristic posture of protecting those who don’t need much protection from the political process but who already have lots of political power, I became more and more concerned about its anti-democratic and anti-human-rights record. I continued to want to make sense of the Court’s doctrines. I wrote a treatise that got very frequently cited around the world and that shaped my teaching about how the Court’s ideas in various areas could be pulled together. But then, after I had done the second edition of that treatise, and it became relied on by a lot of people, I decided [after the first volume] of the third edition, basically, to stop that project.

What were you arguing in the first two editions?

The first was the first effort in probably a hundred years to pull together all of constitutional law. And it led to a rebirth, or flowering, of lots of writing about constitutional law, and writing more focussed on methodology, with different forms of interpretation. I was very excited about that project, and [the second edition] continued it. Most of what I did was to see connections among different areas. I would be writing about commercial regulation, and I would see themes that popped up in areas of civil rights and civil liberties. Or I’d be writing about separation of powers, and I would see problems that arose elsewhere.

And I was always trying to find coherence, because my background in mathematics had led me to be very interested in the deep structures of things. I was working on a Ph.D. in algebraic topology when I rather abruptly shifted from mathematics to law. And so, in my treatise, I developed what I thought of as seven different models of constitutional law. I’m always fascinated by different perspectives and lenses and models. I’ve never thought of law and politics as strictly separate, and efforts by people like Steve Breyer to say that we shouldn’t concede that constitutional law is largely political have always seemed to me to be misleading. That said, I still saw efforts at consistency and concerns about avoiding hypocrisy from the Court. But those things began getting harder to take seriously.

And then Steve Breyer wrote me a long letter saying, “When are you going to finish the third edition of your treatise?” And I wrote him a letter back, which then was published in various places, saying, “I’m not going to keep doing it. And here’s why.” It was a letter that described how I thought constitutional law had really lost its coherence.

At one level, you’re saying something really changed with the Court. But earlier you said that the Court has always had some history of protecting the powerful and not protecting minority rights or the powerless. So did something change, or did the Court just have this brief period, after the Second World War, when you saw it as different before returning to its normal posture?

I think there’s always been a powerful ideological stream, but the ascendant ideology in the nineteen-sixties and seventies was one that I could easily identify with. It was the ideology that said the relatively powerless deserve protection, by an independent branch of government, from those who would trample on them.

Right. The Warren Court was also ideological; it just happened to be an ideology that you or I might agree with.

Exactly. No question. It was quite ideological. Justice Brennan had a project whose architecture was really driven by his sense of the purposes of the law, and those purposes were moral and political. No question about it. I’m not saying that somehow the liberal take on constitutional law is free of ideology. There was, however, an intellectually coherent effort to connect the ideology with the whole theory of what the Constitution was for and what the Court was for. Mainly, the Court is an anti-majoritarian branch, and it’s there to protect minorities and make sure that people are fairly represented. I could identify with that ideology. It made sense to me, and I could see elements of it in various areas of doctrine. But as that fell apart, and as the Court reverted to a very different ideology, one in which the Court was essentially there to protect propertied interests and to protect corporations and to keep the masses at bay—that’s an ideology, too, but it was not being elaborated in doctrine in a way that I found even coherent, let alone attractive.

Maybe I’m wrong about this, but I see more internal contradiction and inconsistency in the strands of doctrine of the people who came back into power with the Reagan Administration and the Federalist Society. I’m not the person to make sense of what they’re doing, because it doesn’t hang together for me. Even if I could play the role that I think I did play with a version that I find more morally attractive, it’s a project that I would regard as somewhat evil and wouldn’t want to take part in.

I’m not trying to paint the picture that says everything was pure logic and mathematics and apolitical and morally neutral in the good days of the Warren Era, and incoherent and ideologically driven in other times. I think that would be an unfair contrast. So I hope what I’ve said to you makes it a little clearer.

You wrote a rather striking piece in The New York Review of Books recently, called “Politicians in Robes,” where you take issue with Breyer essentially still believing that the Court can be apolitical. How should we view the Court now? I think that there is a tendency to say, “These guys are politicians, and they make partisan choices the way anyone else does.”

I guess I think citizens should look at the Court as an inherently political institution, which ideally would, however, offset the aspects of politics in which those who already have power accumulate more of it at the expense of ordinary people and people who are downtrodden or subordinated or subjugated. And people should be critical of the Court when it departs from that function, because then they should say to themselves, “Who are these guys, who essentially were not elected, are independent, are secure and protected? What’s the point of protecting them if they are simply protecting those in power already?” Their independence is of value precisely when they perform an important function: both making democracy work better and protecting those who can’t protect themselves effectively through the political process. People should say to themselves, “When they’re not performing that function, then we really ought not to respect their work and give it a lot of weight.”

Now you or I (unworthy reactionaries that we are) may be inclined to think that the Supreme Court’s job is to interpret the law correctly, strictly in accordance with the Constitution.

Professor Tribe, as we see above, has a completely different theory. In his view, the Supreme Court’s real purpose is to afflict the powerful and enforce, at any cost, the interests of minorities, the “downtrodden or subordinated or subjugated.”

Professor Tribe is indifferent, or actively hostile, to the actual text and meaning of the Constitution, it being obviously in his view the work of dead white males bent only upon protecting the interests of rich white men exactly like themselves.

Professor Tribe’s sympathy for, and emotional identification with, minorities, the poor, and the oppressed, his post-observant-Judaic reflexive Leftism, in his view, apparently rises to a level of significance more worthy of enforcement than the authentic meaning of the Constitution’s text or the intentions of the framers. Pardon me for finding this more than a little intellectually self-indulgent.

More than merely self-indulgent, personally, I tend to look upon the vice-like-grip of representatives of the Elite Gentry Left, like Professor Tribe, upon the cause of “the poor, minorities, and the oppressed,” to be in reality in the nature of a self-interested tactic.

It would obviously be unbecoming for rich fat cats comfortably ensconced in the most prestigious positions in Society to be found asking for greater powers, more privileges, more authority for themselves. The peasants might respond with indignation. But, when, you see, they point to a category of victims, defined specifically as less well off than everybody else, more miserable and more wronged than the rest of all you nobodies, and appoint themselves as the champions and protectors of these lepers and untouchables, it’s a whole new ballgame: the sky’s the limit what they can demand. It’s a very old con game, and a very effective one. That’s why so many play it.

15 May 2021

“A jug of rice wine infused with two hundred baby rodents; a dessert made of millions of crushed flies. Jiayang Fan spoke with the creator of the Disgusting Food Museum, in Sweden, which is located in a shopping mall and is designed with an eye for Instagram. But the playful surroundings belie the museum’s more serious messages about who gets to decide which foods are “disgusting,” and how, if we want to live more lightly on the planet, we need to broaden our palates. Just maybe don’t start out with cans of surströmming, a fermented herring. The museum director informed Fan that these fish have induced more vomiting than any other item at the museum.”

14 May 2021

Rebecca Mead serves up the traditional expansive New Yorker essay on the Cerne Abbas Giant in response to recent dating efforts making the news.

The Cerne Giant is so imposing that he is best viewed from the opposite crest of the valley, or from the air. He is a hundred and eighty feet tall, about as high as a twenty-story apartment building. Held aloft in his right hand is a large, knobby club; his left arm stretches across the slope. Drawn in an outline formed by trenches packed with chalk, he has primitive but expressive facial features, with a line for a mouth and circles for eyes. His raised eyebrows were perhaps intended to indicate ferocity, but they might equally be taken for a look of confusion. His torso is well defined, with lines for ribs and circles for nipples; a line across his waist has been understood to represent a belt. Most well defined of all is his penis, which is erect, and measures twenty-six feet in length. Were the giant not protectively fenced off, a visitor could comfortably lie down within the member and take in the idyllic vista beyond.

RTWT

Outline version (outside paywall).

14 Nov 2020

“. . . and if you look off the left-hand side of the plane you’ll see the smoldering ruins of what’s left of our civilization . . .â€

02 Aug 2020

E. Tammy Kim, Yale 2002.

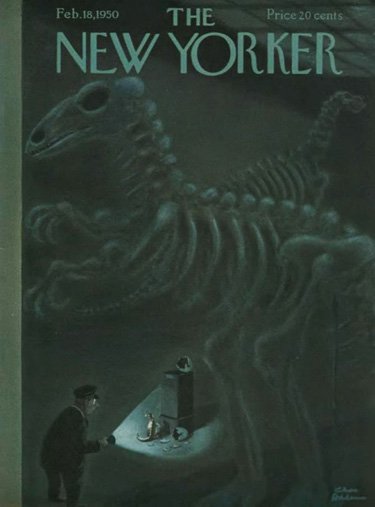

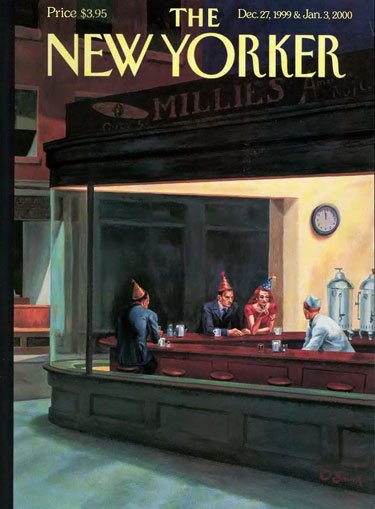

There was a time when the New Yorker viewed itself as the voice of an imaginary top-hatted and monocled urban sophisticate of impeccable White Anglo-Saxon pedigree, whimsically named Eustace Tilley, whose costume hinted at residence in an imaginary Regency Manhattan, drawn scrutinizing skeptically a passing butterfly, evidently attempting to determine if its quality rises to a level worthy of his recognition and acquaintance.

Today’s New Yorker of almost a century later, like the American Establishment it speaks to, and for, has changed most remarkably.

Its authors are still dyed-in-the-wool representatives of the community of fashion, channeling the Zeitgeist and delivering up the intellectual results of educations at the finest universities in the land, like Yale, just for instance. But, where the old New Yorker was devoted to the eternal quest for top quality writing and exhibitions of high intelligence, today’s New Yorker is an angry, self-righteous fanatic, a Savanarola or Robespierre, devoted to the Revolution in which the likes of Eustace Tilley will be indicted for limitless historical crimes against a constellation of Identity Groups, convicted and guillotined in Manhattan’s version of the Place de la Concorde.

The magazine’s pages will, henceforth, be devoted to organizing and agitating on behalf of all officially-recognized Oppressed Categories; denouncing and destroying Eustace, everything he stands for, and all his relations; and negotiating the precise future status and power relations of every category of victim in the new Majority.

E. Tammy Kim, in the latest New Yorker, is endeavoring to book some advantageous accommodations on Karl Marx’s Arc for Koreans like herself, when the Rising Tide of Color in the imminent future sweeps away the white American majority, the Founding Fathers, God, apple pie, and the entire former canon of Western History and Culture.

The most recent time I was mistaken for white was a few weeks ago, on that most ignoble medium of Zoom. This time, it was a virtual organizing meeting for a tenant-rights group in New York. The handful of people on the call were mostly friends, all of us concerned about protecting neighbors from eviction, particularly during the pandemic. As we discussed the welfare of longtime renters, and as Black Lives Matter protests erupted a few blocks away, a new member of the group tried to thoughtfully turn the lens.

“We’re talking gentrification, but everyone on this call is white,†she said.

“Actually, I’m not white,†I replied.

“Oh, I just meant that we have no people of color,†she said. “No Black or brown people.â€

I nodded to clear the air and because I found the exchange more intriguing than discomfiting. Though our organizing group included people of all races, it was true that this particular meeting was overwhelmingly white. The woman had thus invoked “people of color†and “Black and brown†to mean renters who were Black or Latinx, older and lower-income. I wondered if she would have said the same thing if younger, wealthier newcomers who happened to have dark skin had been on the call. Would they qualify as “people of color�

I want to clarify that I do not look white. I am Korean-American and appear very much the part. So the woman’s mistake was not centered in her visual cortex but, rather, in whatever organs of intellect and affect tell us that one thing is not like the other. It was a short, mundane encounter of the kind I’ve had many times before, with both Black and white people.

E. Tammy Kim, strangely enough to my own mind, emerged from dear old Yale, Philosophy degree in hand, apparently astonishingly well versed on the opinions of every minor communist academic crackpot at every cow college in the country. She can quote chapter and verse concerning every real and suppositious grievance for every malcontent identity group, but she somehow overlooks entirely the sunny side of life.

Personally, I think she might forgive America its 19th Century Ban on Chinese Immigration and our insufficient wage payments to migrant labor and poor whites when she considers that America also saved half of her ancestral homeland from Communist despotism and slavery and, despite all our racism and White Supremacy, let her family come here, where instead of digging ditches and eating turnips like the typical North Korean, she got to revel in the luxury of Yale’s Trumbull College and publish regularly in the Times and the New Yorker.

One asks oneself: What does it take to satisfy this chick?

[A] growing number of activists and commentators say that “people of color†no longer works. The central point of Black Lives Matter, after all, has been to condemn the mortal threat of anti-Black racism and name the particular experiences of the Black community. “People of color,†by grouping all non-whites in the United States, if not the world, fails to capture the disproportionate per-capita harm to Blacks at the hands of the state. The practical use of “people of color†has also devolved into “diversity†rhetoric, invoked by a white managerial class that may be willing to hire fair-skinned Latinx or Asian expats but not Black people, or by non-Black minorities who lean on the term only when it’s convenient. Say Black if you mean Black. S. Neyooxet Greymorning, a professor of anthropology and Native American studies at the University of Montana, told me that “people of color†tends to blot out the concerns of not only Black people but those who claim the “political,†non-racial category of indigenous. “The problem is, even when you have those kinds of alliances, normally one group will rise to the top and dominate the other groups,†he said.

To be clear, Greymorning did not mean to contest the present focus on Black lives. He applauded it and noted that every mobilization needs a definable aim; ending all discriminatory violence would be too large and blurry a goal to structure a movement. But it’s also the case that—since the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, in 2013—some intellectuals and activists have contended that anti-Blackness alone can explain U.S. history, and that all other campaigns for racial and social justice are tributaries of the Black liberation struggle. Rejecting the term “people of color†may be of little consequence, but rejecting the solidarity it implies can result in an inaccurate and unduly limiting world view.

As Margo Okazawa-Rey, a professor emerita at San Francisco State University who participated in the Black feminist Combahee River Collective of the nineteen-seventies, put it, “The history of this country is told from the East Coast,†thereby privileging the Black-white binary. This lens is foundational, and central to our racial imaginary, but it should not be the only one. The enslavement of Black people on this continent—and the caste system devised to maintain it—cannot fully explain the attempted genocide of indigenous peoples, a decades-long ban on Chinese immigration, the mass deportations and lynching of Mexican migrant workers, the crackdown on Arab and Muslim communities after 9/11, or our wars in the Philippines and Iraq. The wealth of the United States owes not only to slavery but also the exploitation of migrant workers and poor whites, and the theft of land and natural resources here and abroad. And although it is now common to attribute the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 solely to the civil-rights movement, its more proximate cause was the injunction of anti-Communist foreign policy.

Clearly, as we see below, it takes, speaking as a member of the current European-descended majority, nothing less than our replacement, supplanting, defeat and cultural and political elimination.

This cute little Asian girl is really a raving communist and a spectacularly virulent racist.

What seems obvious is: Considering her views, why doesn’t she just go to Cuba, or North Korea, where she doesn’t need to organize, agitate, or struggle at all. Her vision of “universal liberation, across race and class, against white supremacy and U.S. empire” is already perfectly in place in those countries.

The problem with sorting based on the dominant racial binary, according to the philosopher Linda MartÃn Alcoff, of Hunter College, is that it creates a defeatist paradigm “in which a very large white majority confronts a relatively small Black minorityâ€â€”when, in fact, whites in the U.S. will soon be outnumbered by people of color.

Eustace Tilley, cover of first New Yorker, 1925.

08 Jun 2020

The New Yorker has got a previously unpublished fishing story by Ernest Hemingway. Good stuff!

That year we had planned to fish for marlin off the Cuban coast for a month. The month started the tenth of April and by the tenth of May we had twenty-five marlin and the charter was over. The thing to have done then would have been to buy some presents to take back to Key West and fill the Anita with just a little more expensive Cuban gas than was necessary to run across, get cleared, and go home. But the big fish had not started to run.

“Do you want to try her another month, Cap?†Mr. Josie asked. He owned the Anita and was chartering her for ten dollars a day. The standard charter price then was thirty-five a day. “If you want to stay, I can cut her to nine dollars.â€

Enjoy.

29 Aug 2019

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, La baigneuse endormie [The Sleeping Bather], 1897, Winterthur.

The New Yorker rather outdid itself in the “PC Assaults on Civilization” Sweepstakes this week with Peter Schjedahl‘s smackdown of Renoir.

Targeting Renoir as problematic, sexist, and prurient seems not only Philistine, Puritanical, and just plain unkind, it seems to constitute a downright fascistic rejection of la douceur de vivre.

Roger Kimball identifies precisely what is so fundamentally wrong here in the Spectator.

Schjeldahl’s judgments about Renoir are a fastidiously composed congeries of up-to-the-minute elite opinion. There at The New Yorker, everyone will agree with Schjeldahl about Renoir or — the more important point — about subjugating him to the strictures prevalent among the beautiful people circa 2019. What made Schjeldahl’s essay notorious were not his particular judgments about Renoir’s art or character but rather his imperative anachronism. ‘An argument is often made that we shouldn’t judge the past by the values of the present,’ Schjeldahl writes, ‘but that’s a hard sell in a case as primordial as Renoir’s.’

Is it? As Ed Driscoll pointed out at Instapundit, Schjeldahl’s essay is sterling example of what C.S. Lewis described as ‘chronological snobbery,’ the belief that ‘the thinking, art, or science of an earlier time is inherently inferior to that of the present, simply by virtue of its temporal priority or the belief that since civilization has advanced in certain areas, people of earlier time periods were less intelligent.’ If, Driscoll observes, we add the toxic codicil that those previous times were ‘therefore wrong and also racist’ we would have ‘a perfect definition of today’s SJWs.’

Exactly. Driscoll goes on to quote Jon Gabriel, who has anatomized this process under the rubric of ‘cancel culture,’ a culture of willful and barbaric diminishment.

‘Cancel culture,’ Gabriel notes, ‘is spreading for one simple reason: it works. Instead of debating ideas or competing for entertainment dollars, you can just demand anyone who annoys you to be cast out of polite society.’ It’s already come to a college campus near you, and is epidemic on social and other sorts of media. not to mention through the so-called ‘Human Resources’ departments of many companies. Wander ever so slightly outside the herd of independent minds and, bang, it’s ostracism or worse.

There are many ironies attendant on the spread of ‘cancel culture.’ One irony is that, despite its origins in the effete eyries of elite culture, the new ethic of conformity exhibits an extraordinary and intolerant provincialism. The British man of letters David Cecil got to the nub of this irony when, in his book Library Looking-Glass, he noted that ‘there is a provinciality in time as well as in space.’

‘To feel ill-at-ease and out of place except in one’s own period is to be a provincial in time. But he who has learned to look at life through the eyes of Chaucer, of Donne, of Pope and of Thomas Hardy is freed from this limitation. He has become a cosmopolitan of the ages, and can regard his own period with the detachment which is a necessary foundation of wisdom.’

It has become increasingly clear as the imperatives of political correctness make ever greater inroads against free speech and the perquisites of dispassionate inquiry that the battle against this provinciality of time is one of the central cultural tasks of our age. It is a battle from which the traditional trustees of civilization — schools and colleges, museums, many churches — have fled. Increasingly, the responsibility for defending the intellectual and spiritual foundations of Western civilization has fallen to individuals and institutions that are largely distant from, when they are not indeed explicitly disenfranchised from, the dominant cultural establishment.

Leading universities today command tax-exempt endowments in the tens of billions of dollars. Leading cultural organs like The New Yorker and The New York Times parrot the ethos of the academy and exert a virtual monopoly on elite opinion.

But it is by no means clear, notwithstanding their prestige and influence, whether they do anything to challenge the temporal provinciality of their clients. No, let me amend that: it is blindingly clear that they do everything in their considerable power to reinforce that provinciality, not least by their slavish capitulation to the dictates of the enslaving presentism of political correctness.

RTWT

25 Aug 2019

Amy Wax, a professor at Penn Law, has gravely jeopardized both her career and personal reputation, tip-toeing around the edge of the Overton Window, by questioning the absolute equality of mankind’s cultures.

In Nazi Germany, when somebody got this far out of line, they’d get a visit from the Gestapo. In the Soviet Union, it would be the N.K.V.D. rapping on the door. In contemporary America, the New Yorker sends a professional apparatchik like Isaac Chotiner to assassinate by interview.

RTWT

If a politician with a history of anti-Semitism says, “The Jews control a giant chunk of Hollywood,†and he starts ranting about that, do you think that the proper response is to say, “Well, let’s investigate exactly how much power Jews have in Hollywood, and, if it’s true that Jews have a lot of power in Hollywood, we should let this person rant about how much power the Jews have in Hollywood, because, after all, it is true?†And so anything that is true can’t be racist. What do you think of my example there?

Well, here you go with the “racist†again. I mean, is it true? Are there a lot of Jews in Hollywood? Yeah, there are. Let’s start with that—there are a tremendous number of Jews, out of proportion to their numbers in the population within the universities, within the media, in the professions. We can ask all of these questions, and you know what? They admit of an answer. But essentially what the left is saying is: We can’t even answer the question. We can’t. Once we’ve labelled something racist, the conversation stops. It comes to a halt, and we are the arbiters of what can be discussed and what can’t be discussed. We are the arbiters of the words that can be used, of the things that can be said.

I can tell you, and, once again, this is just from the mail I get, from the e-mails I get, from the people I talk to, that kind of move is deeply resented.

I’m just trying to make a point about how something could be true but still racist or used in a racist manner. Not that I think that everything you said is true.

Once again, you’d have to define racism. You’re basically saying any generalization about a group, whether true or false—and we know it doesn’t apply to everybody in the group, because that’s just a straw man—is racist. I mean, we could do “sexist,†right?

We could.

So, women, on average, are more agreeable than men. Women, on average, are less knowledgeable than men. They’re less intellectual than men. Now, I can actually back up all those statements with social-science research.

You can send me links for women are “less intellectual than men.†I’m happy to include that in the piece if you have a good link for that.

O.K., well, there’s a literature in Britain, a series of papers that were done, and I need to look them up, that show that women are less knowledgeable than men. They know less about every single subject, except fashion. There is a literature out of Vanderbilt University that looks at women of very high ability—so, controlling for ability—and, starting in adolescence, women are less interested in the single-minded pursuit of abstract intellectual goals than men. They want more balance in their life. They want more time with family, friends, and people. They’re less interested in working hard on abstract ideas. You can put together a database that shows that. The person who has the literature is a man named David Lubinski, and he shows that intelligence isn’t what’s driving it. It is interest, orientation, what people want to spend their time doing.

Now, is that sexist? We can argue all day about whether it is sexist. We can argue from morning till night. And it is sterile. It is pointless. Let’s talk about the actual findings and what implications they have for policy, for expectations.

[Wax sent links to two studies whose lead author is Richard Lynn, a British psychologist who is known for believing in racial differences in intelligence, supporting eugenics, and associating with white supremacists. (She also shared the Wikipedia page for “general knowledge,†which cites several of Lynn’s studies.) David Lubinski, a professor of psychology at Vanderbilt, clarified that his research was about the life choices of men and women and did not address claims such as women being less intellectual than men.]

Professor Wax, throughout the interview, is trying to identify the Progressive restriction of speech and thought as a serious national and academic problem. Chotiner, throughout the interview, is looking for some damaging quotes he can use to hang her.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'New Yorker' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|