He looks rather menacing.

They Start Young in Ireland

Ballinagore Harriers, Foxhunting, Ireland

Photo: Siobhan English.

Great picture of eight-year-old Stephen Murphy enjoying his first ever day’s hunting today, clearing a double bank!, and wearing the Wexford colors, with the Ballinagore Harriers near Enniscorthy.

———————————————

Here’s a 2016 video of the same hunt.

Kenosha Prosecutor Demonstrates AR-15 For Jury

Babylon Bee, Gun Safety, Kenosha, Kyle Rittenhouse, Satire, Wisconsin

Babylon Bee: Prosecutor Proves How Deadly AR-15 Is By Accidentally Shooting 7 Jurors.

Swiss Shooting Champion Retires at Age 85

Swiss Karabiner Modell 1931, Switzerland, Target Shooting, Toni Hacki

Reuters has a poignant shooting story from Switzerland.

Surrounded by other sharpshooters, scraggly-beareded Toni Hacki lifted his long rifle and took aim across the Ruetli meadow where Switzerland was founded in 1291, just as he had done for the past 51 years.

But this time, his performance didn’t live up to his standards, and he decided it would be his last.

“Today went badly. My vision failed me,” grumbled Hacki, who blamed the sun getting in his eyes as he aimed.

More than 1,000 sharpshooters gathered on the shores of Lake Lucerne last week for the annual Ruetli Shooting, an event that has been held since the 19th century, which pays homage to the country’s foundation as a medieval confederation of cantons.

Many of the shooters competed using military-style black rifles, wearing contemporary sports gear. Hacki wore a thick button-up leather jacket. The barrel of his gun was wooden (sic)*.

Two decades ago, Hacki was the champion. Next year, he will return as a spectator, he said.

“I will come back but I won’t shoot. That’s over now.”

* He means the stock is wood.

______________________________________

There’s a famous story the Swiss like to tell:

“In 1912, the German Kaiser visited Switzerland and asked a Swiss minister what the quarter of a million strong Swiss army would do if Germany invaded with 500,000 troops. The minister replied: “Shoot twice and go home.”

Grapefruit: Stranger Than You Think

Botany, Grapefruit, History

Right from the moment of its discovery, the grapefruit has been a true oddball. Its journey started in a place where it didn’t belong, and ended up in a lab in a place where it doesn’t grow. Hell, even the name doesn’t make any sense.

THE CITRUS FAMILY OF FRUITS is native to the warmer and more humid parts of Asia. The current theory is that somewhere around five or six million years ago, one parent of all citrus varieties splintered into separate species, probably due to some change in climate. Three citrus fruits spread widely: the citron, the pomelo, and the mandarin. Several others scattered around Asia and the South Pacific, including the caviar-like Australian finger lime, but those three citrus species are by far the most important to our story.

With the exception of those weirdos like the finger lime, all other citrus fruits are derived from natural and, before long, artificial crossbreeding, and then crossbreeding the crossbreeds, and so on, of those three fruits. Mix certain pomelos and certain mandarins and you get a sour orange. Cross that sour orange with a citron and you get a lemon. It’s a little bit like blending and reblending primary colors. Grapefruit is a mix between the pomelo—a base fruit—and a sweet orange, which itself is a hybrid of pomelo and mandarin.

Because those base fruits are all native to Asia, the vast majority of hybrid citrus fruits are also from Asia. Grapefruit, however, is not. In fact, the grapefruit was first found a world away, in Barbados, probably in the mid-1600s. The early days of the grapefruit are plagued by mystery. Citrus trees had been planted casually by Europeans all over the West Indies, with hybrids springing up all over the place, and very little documentation of who planted what, and which mixed with which. Citrus, see, naturally hybridizes when two varieties are planted near each other. Careful growers, even back in the 1600s, used tactics like spacing and grafting (in which part of one tree is attached to the rootstock of another) to avoid hybridizing. In the West Indies, at the time, nobody bothered. They just planted stuff. Read the rest of this entry »

Yale Has More Damned Administrators Than Undergraduates!

Bureaucratic Bloat, Peter Salovey, Un Autre Jolie Cadeau de la Revolution Francaise, Yale

The numbers:

4,664 undergraduate students

4,962 faculty

5,042 administrators

——————————————

“I think we don’t yet have a Vice President for the rights of the left-handed, but I haven’t checked this month.” — Professor Leslie Brisman.

——————————————

Over the last two decades, the number of managerial and professional staff that Yale employs has risen three times faster than the undergraduate student body, according to University financial reports. The group’s 44.7 percent expansion since 2003 has had detrimental effects on faculty, students and tuition, according to eight faculty members.

In 2003, when 5,307 undergraduate students studied on campus, the University employed 3,500 administrators and managers. In 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on student enrollment, only 600 more students were living and studying at Yale, yet the number of administrators had risen by more than 1,500 — a nearly 45 percent hike. In 2018, The Chronicle of Higher Education found that Yale had the highest manager-to-student ratio of any Ivy League university, and the fifth highest in the nation among four-year private colleges.

According to eight members of the Yale faculty, this administration size imposes unnecessary costs, interferes with students’ lives and faculty’s teaching, spreads the burden of leadership and adds excessive regulation. By contrast, administrators noted much of this increase can be attributed to growing numbers of medical staff, and that the University has proportionally increased its faculty size.

“I had remarked to President Salovey on his inauguration that I thought the best thing he could do for Yale would be to abolish one deanship or vice presidency every year of what I hoped would be a long tenure in that position,” professor of English Leslie Brisman wrote in an email to the News. “Instead, it has seemed to me that he has created one upper level administrative position a month.”

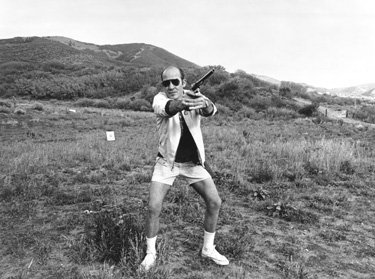

Hunter Thompson “Sitting in Hell. Handcuffed to Richard Nixon.”

Bad Behavior, Book Reviews, Gonzo Journalism, Hunter Thompson

Kevin Mims, in Quillette, reviews High White Notes: The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism by David S. Wills with a very amusing account of just how huge an asshole Hunter Thompson really was.

Every few pages of Wills’s book brings another example of Thompson screwing people over. Thompson always had difficulty with self-discipline, but his inability to produce any work was exacerbated by his cocaine abuse. This was certainly bad for his career. But it was also bad for the careers of those in his orbit. Steadman joined Thompson in Zaire where Rolling Stone had sent them to cover the Ali-Foreman fight. Steadman was eager to see the fight, but Thompson told him, “I didn’t come all this way to watch a couple of niggers beat the shit out of each other.” On the morning of the fight, Steadman frantically tried to find Thompson, who had their press passes, but Thompson had sold them and used the money to buy cocaine and marijuana. When Steadman finally found him, he was stoned and was throwing large quantities of marijuana into the hotel pool. …

When the US military began pulling out of Vietnam, Wenner asked Thompson to cover it for Rolling Stone. Thompson agreed but began to lose his nerve as his departure date drew near. Wenner asked New York Times war correspondent Gloria Emerson to try to bolster Thompson’s confidence. The phone calls between them were recorded (Thompson—like Nixon—recorded many of his phone calls and conversations), and Emerson can be heard telling him how to cover the story, passing him the details of her own contacts and translators, and offering to provide him with all the facts about Vietnam that he lacked.

Thompson finally arrived in Vietnam in April of 1975 (more than a decade after the mainstream journalists he hated began covering the story on a daily basis). He took a lot of opium, mingled with prostitutes, and generally behaved like a clown in order to entertain the other journalists, many of whom were fans of his work. But, as Wills remarks, his behavior “wasn’t as funny in real life.” The other journalists quickly realized that his antics might get him—and them—killed. At least 60 Western journalists were killed covering the war and, as Wills points out, “few of them were running around high on drugs.” Tape recordings make it clear that he was hopelessly out of his element. The other journalists can be heard laughing at his ignorance of the facts on the ground. They teased him about the fact that he hadn’t managed to write a word about the Ali-Foreman fight when Norman Mailer had managed to write a groundbreaking piece for Playboy.

Later, by himself, Thompson can be heard spitting out the words, “Fuck them!” on the recorder. At one point, stoned out of his mind and believing he was chasing “four giant fucker pterodactyls,” Thompson wandered dangerously close to the front line. Several journalists had to put themselves in harm’s way to bundle him into a jeep and drive him back to relative safety. … Read the rest of this entry »

Martinmas aka Armistice Day aka Veterans Day

Armistice Day, Hagiography, Martinmas, Traditions, Veterans Day

–An annual post–

WWI came to an end by an armistice arranged to occur at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918. The date and time, selected at a point in history when mens’ memories ran much longer, represented a compliment to St. Martin, patron saint of soldiers, and thus a tribute to the fighting men of both sides. The feast day of St. Martin, the Martinmas, had been for centuries a major landmark in the European calendar, a date on which leases expired, rents came due; and represented, in Northern Europe, a seasonal turning point after which cold weather and snow might be normally expected.

It fell about the Martinmas-time, when the snow lay on the borders…

—Old Song.

From Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, 1869:

St. Martin, the son of a Roman military tribune, was born at Sabaria, in Hungary, about 316. From his earliest infancy, he was remarkable for mildness of disposition; yet he was obliged to become a soldier, a profession most uncongenial to his natural character. After several years’ service, he retired into solitude, from whence he was withdrawn, by being elected bishop of Tours, in the year 374.

The zeal and piety he displayed in this office were most exemplary. He converted the whole of his diocese to Christianity, overthrowing the ancient pagan temples, and erecting churches in their stead. From the great success of his pious endeavours, Martin has been styled the Apostle of the Gauls; and, being the first confessor to whom the Latin Church offered public prayers, he is distinguished as the father of that church. In remembrance of his original profession, he is also frequently denominated the Soldier Saint.

The principal legend, connected with St. Martin, forms the subject of our illustration, which represents the saint, when a soldier, dividing his cloak with a poor naked beggar, whom he found perishing with cold at the gate of Amiens. This cloak, being most miraculously preserved, long formed one of the holiest and most valued relics of France; when war was declared, it was carried before the French monarchs, as a sacred banner, and never failed to assure a certain victory. The oratory in which this cloak or cape—in French, chape—was preserved, acquired, in consequence, the name of chapelle, the person intrusted with its care being termed chapelain: and thus, according to Collin de Plancy, our English words chapel and chaplain are derived. The canons of St. Martin of Tours and St. Gratian had a lawsuit, for sixty years, about a sleeve of this cloak, each claiming it as their property. The Count Larochefoucalt, at last, put an end to the proceedings, by sacrilegiously committing the contested relic to the flames.

Another legend of St. Martin is connected with one of those literary curiosities termed a palindrome. Martin, having occasion to visit Rome, set out to perform the journey thither on foot. Satan, meeting him on the way, taunted the holy man for not using a conveyance more suitable to a bishop. In an instant the saint changed the Old Serpent into a mule, and jumping on its back, trotted comfortably along. Whenever the transformed demon slackened pace, Martin, by making the sign of the cross, urged it to full speed. At last, Satan utterly defeated, exclaimed:

Signa, te Signa: temere me tangis et angis:

Roma tibi subito motibus ibit amor.’In English—

‘Cross, cross thyself: thou plaguest and vexest me without necessity;

for, owing to my exertions, thou wilt soon reach Rome, the object of thy wishes.’The singularity of this distich, consists in its being palindromical—that is, the same, whether read backwards or forwards. Angis, the last word of the first line, when read backwards, forming signet, and the other words admitting of being reversed, in a similar manner.

The festival of St. Martin, happening at that season when the new wines of the year are drawn from the lees and tasted, when cattle are killed for winter food, and fat geese are in their prime, is held as a feast-day over most parts of Christendom. On the ancient clog almanacs, the day is marked by the figure of a goose; our bird of Michaelmas being, on the continent, sacrificed at Martinmas. In Scotland and the north of England, a fat ox is called a mart, clearly from Martinmas, the usual time when beeves are killed for winter use. In ‘Tusser’s Husbandry, we read:

When Easter comes, who knows not then,

That veal and bacon is the man?

And Martilmass beef doth bear good tack,

When country folic do dainties lack.’Barnaby Googe’s translation of Neogeorgus, shews us how Martinmas was kept in Germany, towards the latter part of the fifteenth century

‘To belly chear, yet once again,

Doth Martin more incline,

Whom all the people worshippeth

With roasted geese and wine.

Both all the day long, and the night,

Now each man open makes

His vessels all, and of the must,

Oft times, the last he takes,

Which holy Martin afterwards

Alloweth to be wine,

Therefore they him, unto the skies,

Extol with praise divine.’A genial saint, like Martin, might naturally be expected to become popular in England; and there are no less than seven churches in London and Westminster, alone, dedicated to him. There is certainly more than a resemblance between the Vinalia of the Romans, and the Martinalia of the medieval period. Indeed, an old ecclesiastical calendar, quoted by Brand, expressly states under 11th November: ‘The Vinalia, a feast of the ancients, removed to this day. Bacchus in the figure of Martin.’ And thus, probably, it happened, that the beggars were taken from St. Martin, and placed under the protection of St. Giles; while the former became the patron saint of publicans, tavern-keepers, and other ‘dispensers of good eating and drinking. In the hall of the Vintners’ Company of London, paintings and statues of St. Martin and Bacchus reign amicably together side by side.

On the inauguration, as lord mayor, of Sir Samuel Dashwood, an honoured vintner, in 1702, the company had a grand processional pageant, the most conspicuous figure in which was their patron saint, Martin, arrayed, cap-Ã -pie, in a magnificent suit of polished armour; wearing a costly scarlet cloak, and mounted on a richly plumed and caparisoned white charger: two esquires, in rich liveries, walking at each side. Twenty satyrs danced before him, beating tambours, and preceded by ten halberdiers, with rural music. Ten Roman lictors, wearing silver helmets, and carrying axes and fasces, gave an air of classical dignity to the procession, and, with the satyrs, sustained the bacchanalian idea of the affair.

A multitude of beggars, ‘howling most lamentably,’ followed the warlike saint, till the procession stopped in St. Paul’s Churchyard. Then Martin, or his representative at least, drawing his sword, cut his rich scarlet cloak in many pieces, which he distributed among the beggars. This ceremony being duly and gravely performed, the lamentable howlings ceased, and the procession resumed its course to Guildhall, where Queen Anne graciously condescended to dine with the new lord mayor.