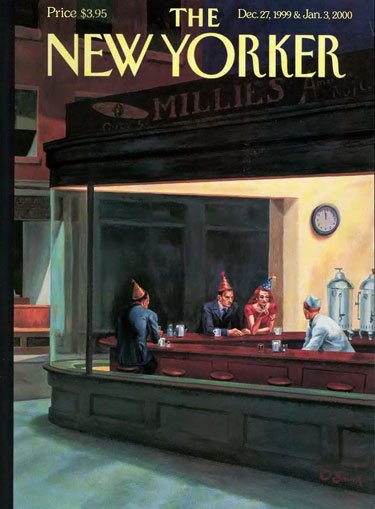

Category Archive 'New Yorker'

06 Aug 2019

Nathan Heller

Leave it to the New Yorker to assign appraisal of some automotive-think books to a Jewish nerd who doesn’t know how to drive and who is afraid of cars.

Was the Automotive Era a Terrible Mistake?

For a century, we’ve loved our cars. They haven’t loved us back.

According to Heller, the triumph of the internal combustion engine was just another expression of toxic masculinity. He looks forward approvingly, from his Blue perspective, to a future of self-driving cars. No more autonomy. No more individualism. What could be more Blue State? What could be better?

You kind of wonder if the New Yorker would have given John Ruskin space for a column on making love to a woman or assigned Helen Keller to review Impressionist paintings.

Come friendly bombs and fall on Brooklyn!

08 May 2019

Prices will be going on on pre-emissions Beetles and people will be reprinting the old John Muir Fix-That-VW-Yourself Guide.

Our Corporate Overlords are rapidly developing driverless cars, and advanced thinkers are already talking about banning driving a car yourself altogether.

The New Yorker recently reported that a new group has been created specifically to defend the Freedom to Drive.

Safety has long been a central argument for the adoption of driverless cars. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, ninety-four per cent of serious crashes are due to human error, and some thirty-five thousand Americans die in traffic-related accidents each year. Autonomous-vehicle makers claim that, by seeing more and responding faster than human drivers can, their cars will save thousands of lives. According to this logic, not adopting autonomous-vehicle technology would be irresponsible—even unethical. “People may outlaw driving cars because it’s too dangerous,†Elon Musk said, at a technology conference, in 2015. (“To be clear, Tesla is strongly in favor of people being allowed to drive their cars and always will be,†he elaborated later, on Twitter. “Hopefully, that is obvious. However, when self-driving cars become safer than human-driven cars, the public may outlaw the latter. Hopefully not.â€)

Perhaps it was inevitable that a nascent right-to-drive movement would spring up in America, where—as fervent gun-rights advocates and anti-vaccinators have shown—we seem intent on preserving freedom of choice even if it kills us. “People outside the United States look at it with bewilderment,†Toby Walsh, an Australian artificial-intelligence researcher, told me. In his book “Machines That Think: The Future of Artificial Intelligence,†from 2018, Walsh predicts that, by 2050, autonomous vehicles will be so safe that we won’t be allowed to drive our own cars. Unlike Roy, he believes that we will neither notice nor care. In Walsh’s view, a constitutional amendment protecting the right to drive would be as misguided as the Second Amendment. “We will look back on this time in fifty years and think it was the Wild West,†he went on. “The only challenge is, how do we get to zero road deaths? We’re only going to get there by removing the human.â€

[Meredith] Broussard [a former software developer who is now a professor of data journalism at New York University, and author of the recent book, “Artificial Unintelligence: How Computers Misunderstand the Worldâ€] has a term for the insistence that computers can do everything better than humans can: technochauvinism. “Most of the autonomous-vehicle manufacturers are technochauvinists,†she said. “The big spike in distracted-driving traffic accidents and fatalities in the past several years has been from people texting and driving. The argument that the cars themselves are the problem is not really looking at the correct issue. We would be substantially safer if we put cell-phone-jamming devices in cars. And we already have that technology.†Like Roy, she strongly disputes both the imminence and the safety of driverless technology. “There comes a point at which you have to divorce fantasy from reality, and the reality is that autonomous vehicles are two-ton killing machines. They do not work as well as advocates would have you believe.â€

Rather than create a constitutional amendment, Broussard argues that drivers should resist laws that would take away their existing rights. Although steering wheels are legally mandatory, the SELF DRIVE Act, which passed the House in 2017, would allow autonomous-vehicle companies to request exemptions from tens of thousands of other regulations. (The Act died in the Senate, but driverless-car companies are urging Congress to take it up again this year.) According to Broussard, the best way to protect the right to drive may be simply to defeat laws that would legalize autonomous vehicles. “We can challenge the notion that autonomous vehicles are inevitable,†she said. “They are not even legal right now.â€

RTWT

Those driverless cars will all be equipped with Internet connections telling the companies that built them and the government exactly where you are and allowing either to disable your vehicle at will. You will need Big Brother’s permission to go anywhere.

Automobiles are already far too loaded with safety features; stripped of conveniences like spare tires, dip sticks, and vent windows; and calculatingly contrived to deny their owners the ability to make repairs themselves.

Our freedom of choice has been incrementally removed year by year. Next they will taking away our Freedom to Drive altogether.

Join the HDA:

09 Feb 2019

I could support any of these three myself.

24 Sep 2018

Steven Hayward saw it coming.

I Told You So

I’ve been saying all week that you could expect another late hit on Brett Kavanaugh over the weekend, and right on schedule, we have the New Yorker story, which, as Paul and Scott have already noted, is pretty thin gruel. But it was absolutely necessary for the left to come up with a story like this, for several reasons. …

[O]ne thing that is true in virtually all cases of sexual predation (think Bill Cosby and Harvey Weinstein) is that there is a pattern of behavior, and usually several other women stepping forward. This trait was conspicuously absent until now. We know that the media—and no doubt large portions of the Democratic establishment—have been trolling feverishly to find another woman with a story. This is the best they can do—a hazy, indirect, recovered memory?

I think this entire late gambit has been one huge bluff by the Democrats, intending to intimidate Republicans into dropping Kavanaugh. I don’t think Dr. Ford has any intention of testifying before the Judiciary Committee this week, and I expect come Wednesday we’ll get a self-serving announcement attacking Chairman Grassley and the Senate Republicans for “bullying†and creating a “hostile environment†in which Dr. Ford cannot “safely†tell her story. At that point, Grassley should call for an immediate committee vote to proceed with the nomination. This latest story in just another attempt to keep the intimidation fires alive. Fine: I say let’s call the bluff and request that Deborah Ramirez, the source of the new allegation, present herself for sworn testimony before the committee.

RTWT

22 Jul 2018

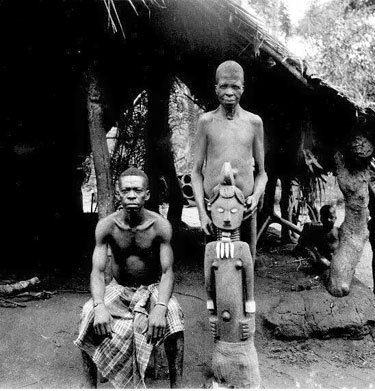

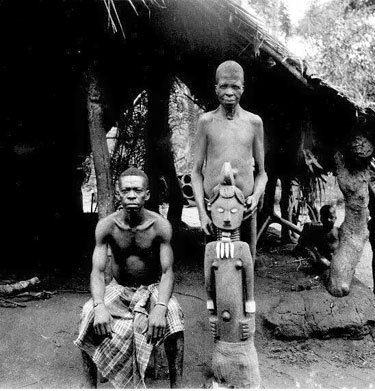

An Igbo with his slave.

Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, in the New Yorker, has news for Ta-Nehisi Coates and all the other noisy SJWs denouncing European Civilization and America for the sin of Slavery: Slavery existed in Africa long before the European Reconnaissance and has continued right down to the present day, long after Slavery was abolished in America and everywhere else in the Western World. Africans, unlike Americans, are proud of the slave-owning ancestors and despise complaining slave descendants.

There is no Atlantic magazine in Nigeria, TNC!

Down the hill, near the river, in an area now overrun by bush, is the grave of my most celebrated ancestor: my great-grandfather Nwaubani Ogogo Oriaku. Nwaubani Ogogo was a slave trader who gained power and wealth by selling other Africans across the Atlantic. “He was a renowned trader,†my father told me proudly. “He dealt in palm produce and human beings.â€

Long before Europeans arrived, Igbos enslaved other Igbos as punishment for crimes, for the payment of debts, and as prisoners of war. The practice differed from slavery in the Americas: slaves were permitted to move freely in their communities and to own property, but they were also sometimes sacrificed in religious ceremonies or buried alive with their masters to serve them in the next life. When the transatlantic trade began, in the fifteenth century, the demand for slaves spiked. Igbo traders began kidnapping people from distant villages. Sometimes a family would sell off a disgraced relative, a practice that Ijoma Okoro, a professor of Igbo history at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, likens to the shipping of British convicts to the penal colonies in Australia: “People would say, ‘Let them go. I don’t want to see them again.’ †Between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries, nearly one and a half million Igbo slaves were sent across the Middle Passage.

My great-grandfather was given the nickname Nwaubani, which means “from the Bonny port region,†because he had the bright skin and healthy appearance associated at the time with people who lived near the coast and had access to rich foreign foods. (This became our family name.) In the late nineteenth century, he carried a slave-trading license from the Royal Niger Company, an English corporation that ruled southern Nigeria. His agents captured slaves across the region and passed them to middlemen, who brought them to the ports of Bonny and Calabar and sold them to white merchants. Slavery had already been abolished in the United States and the United Kingdom, but his slaves were legally shipped to Cuba and Brazil. To win his favor, local leaders gave him their daughters in marriage. (By his death, he had dozens of wives.) His influence drew the attention of colonial officials, who appointed him chief of Umujieze and several other towns. He presided over court cases and set up churches and schools. He built a guesthouse on the land where my parents’ home now stands, and hosted British dignitaries. To inform him of their impending arrival and verify their identities, guests sent him envelopes containing locks of their Caucasian hair.

Funeral rites for a distinguished Igbo man traditionally include the slaying of livestock—usually as many cows as his family can afford. Nwaubani Ogogo was so esteemed that, when he died, a leopard was killed, and six slaves were buried alive with him. My family inherited his canvas shoes, which he wore at a time when few Nigerians owned footwear, and the chains of his slaves, which were so heavy that, as a child, my father could hardly lift them. Throughout my upbringing, my relatives gleefully recounted Nwaubani Ogogo’s exploits. When I was about eight, my father took me to see the row of ugba trees where Nwaubani Ogogo kept his slaves chained up. In the nineteen-sixties, a family friend who taught history at a university in the U.K. saw Nwaubani Ogogo’s name mentioned in a textbook about the slave trade. Even my cousins who lived abroad learned that we had made it into the history books. …

Are you not ashamed of what he did?†I asked.

“I can never be ashamed of him,†he said, irritated. “Why should I be? His business was legitimate at the time. He was respected by everyone around.†My father is a lawyer and a human-rights activist who has spent much of his life challenging government abuses in southeast Nigeria. He sometimes had to flee our home to avoid being arrested. But his pride in his family was unwavering. “Not everyone could summon the courage to be a slave trader,†he said. “You had to have some boldness in you.†…

The British tried to end slavery among the Igbo in the early nineteen-hundreds, though the practice persisted into the nineteen-forties. In the early years of abolition, by British recommendation, masters adopted their freed slaves into their extended families. One of the slaves who joined my family was Nwaokonkwo, a convicted murderer from another village who chose slavery as an alternative to capital punishment and eventually became Nwaubani Ogogo’s most trusted manservant. In the nineteen-forties, after my great-grandfather was long dead, Nwaokonkwo was accused of attempting to poison his heir, Igbokwe, in order to steal a plot of land. My family sentenced him to banishment from the village. When he heard the verdict, he ran down the hill, flung himself on Nwaubani Ogogo’s grave, and wept, saying that my family had once given him refuge and was now casting him out. Eventually, my ancestors allowed him to remain, but instructed all their freed slaves to drop our surname and choose new names. “If they had been behaving better, they would have been accepted,†my father said.

he descendants of freed slaves in southern Nigeria, called ohu, still face significant stigma. Igbo culture forbids them from marrying freeborn people, and denies them traditional leadership titles such as Eze and Ozo. (The osu, an untouchable caste descended from slaves who served at shrines, face even more severe persecution.) My father considers the ohu in our family a thorn in our side, constantly in opposition to our decisions. In the nineteen-eighties, during a land dispute with another family, two ohu families testified against us in court. “They hate us,†my father said. “No matter how much money they have, they still have a slave mentality.

RTWT

08 Mar 2018

Brown marmorated stinkbug (Halyomorpha halys).

The New Yorker lavishes its prose upon the brown marmorated stinkbug.

The species is not native to this country, but in the years since it arrived it has spread to forty-three of the forty-eight continental United States, and—in patchwork, unpredictable, time-staggered ways—has overrun homes, gardens, and farms in one location after another. Four years before Stone’s encounter, a wildlife biologist in Maryland decided to count all the brown marmorated stinkbugs he killed in his own home; he stopped the experiment after six months and twenty-six thousand two hundred and five stinkbugs. Around the same time, entomologists documented thirty thousand stinkbugs living in a shed in Virginia no bigger than an outhouse, and four thousand in a container the size of a breadbox. In West Virginia, bank employees arrived at work one day to find an exterior wall of the building covered in an estimated million stinkbugs.

What makes the brown marmorated stinkbug unique, though, is not just its tendency to congregate in extremely large numbers but the fact that it boasts a peculiar and unwelcome kind of versatility. Very few household pests destroy crops; fleas and bedbugs are nightmarish, but not if you’re a field of corn. Conversely, very few agricultural pests pose a problem indoors; you’ll seldom hear of people confronting a swarm of boll weevils in their bedroom. But the brown marmorated stinkbug has made a name for itself by simultaneously threatening millions of acres of American farmland and grossing out the occupants of millions of American homes. The saga of how it got here, what it’s doing here, and what we’re doing about it is part dystopic and part tragicomic, part qualified success story and part cautionary tale. If you have never met its main character, I assure you: you will soon.

RTWT

IMHO, ground zero is Fauquier County, Virginia. At our home in Hume, we had them throughout the year with a short timeout resulting from the arrival of the first hard frost. They seemed to wake up again, though, right after Christmas. On a typical day, I would collect about 100 stinkbugs using a Dyson hand vacuum. They are here in Central Pennsylvania, too, just not in the same prodigious numbers.

One tip: Taigan puppies will eat stinkbugs!

17 Nov 2017

Bess Kalb chooses, in the New Yorker:

Will Heller, twenty-six

After a month at a Zen silent-meditation retreat, Heller went back to his job at Goldman Sachs as a commodities trader in oil and gas.

Victor Chen, twenty-eight

Chen used an app to hire a person to pick up and deliver a Chipotle burrito to him every night for twenty-two consecutive nights.

Joanna Feldman, twenty-two

Misquoted E. E. Cummings in her rib-cage tattoo.

Rebecca Meyer, twenty-nine

Since earning her M.F.A. in fiction from Columbia, Meyer has been at work writing her début novel in her sprawling Chinatown loft, which was paid for in full by her parents. She has written sixteen pages, and they’re not very good.

Haley DiStefano, twenty-seven

DiStefano is known for posting pictures of her eight-thousand-dollar Cartier bracelets on Instagram, accompanied by the hashtag “#ManicureMonday.â€

David Saperstein, twenty-six

Shared an article about fatalities in Syria accompanied by the comment “So many feels.â€

Oksana Iyovitch, twenty-four

Iyovitch purchased a Scottish Fold kitten after seeing a picture of one on the Twitter feed Cute Emergency. Tried to return the cat to the breeder when it “got too big.â€

Tim Harris, twenty-seven

Started a Bay Area “summer camp†where exhausted tech bros can “unplug†for two thousand dollars a weekend.

Lizzy Balanchine, nineteen

Bad dancer.

Max Kaiserman, twenty-five

Shared upward of two Bernie Sanders-related Facebook posts daily from March through July, then continued to post anti-Hillary articles after she secured the nomination.

Bess Kalb, twenty-nine

Kalb started a screenplay, talked about it to at least thirty friends and family members and two Uber drivers, and then never finished it.

23 Oct 2017

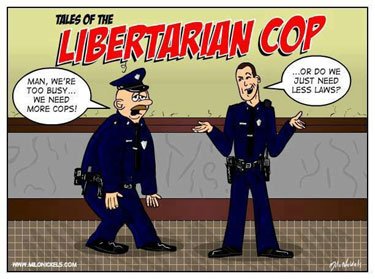

Tom O’Donnell, in the New Yorker, March 31, 1994.

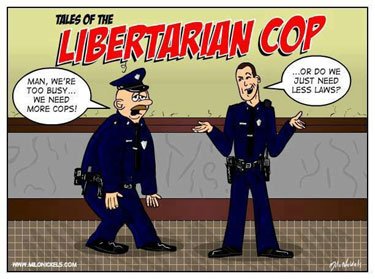

I was shooting heroin and reading “The Fountainhead†in the front seat of my privately owned police cruiser when a call came in. I put a quarter in the radio to activate it. It was the chief.

“Bad news, detective. We got a situation.â€

“What? Is the mayor trying to ban trans fats again?â€

“Worse. Somebody just stole four hundred and forty-seven million dollars’ worth of bitcoins.â€

The heroin needle practically fell out of my arm. “What kind of monster would do something like that? Bitcoins are the ultimate currency: virtual, anonymous, stateless. They represent true economic freedom, not subject to arbitrary manipulation by any government. Do we have any leads?â€

“Not yet. But mark my words: we’re going to figure out who did this and we’re going to take them down … provided someone pays us a fair market rate to do so.â€

“Easy, chief,†I said. “Any rate the market offers is, by definition, fair.â€

He laughed. “That’s why you’re the best I got, Lisowski. Now you get out there and find those bitcoins.â€

“Don’t worry,†I said. “I’m on it.â€

I put a quarter in the siren. Ten minutes later, I was on the scene. It was a normal office building, strangled on all sides by public sidewalks. I hopped over them and went inside.

“Home Depot™ Presents the Police!®†I said, flashing my badge and my gun and a small picture of Ron Paul. “Nobody move unless you want to!†They didn’t.

“Now, which one of you punks is going to pay me to investigate this crime?†No one spoke up.

“Come on,†I said. “Don’t you all understand that the protection of private property is the foundation of all personal liberty?â€

It didn’t seem like they did.

“Seriously, guys. Without a strong economic motivator, I’m just going to stand here and not solve this case. Cash is fine, but I prefer being paid in gold bullion or autographed Penn Jillette posters.â€

Nothing. These people were stonewalling me. It almost seemed like they didn’t care that a fortune in computer money invented to buy drugs was missing.

I figured I could wait them out. I lit several cigarettes indoors. A pregnant lady coughed, and I told her that secondhand smoke is a myth. Just then, a man in glasses made a break for it.

“Subway™ Eat Fresh and Freeze, Scumbag!®†I yelled.

Too late. He was already out the front door. I went after him.

“Stop right there!†I yelled as I ran. He was faster than me because I always try to avoid stepping on public sidewalks. Our country needs a private-sidewalk voucher system, but, thanks to the incestuous interplay between our corrupt federal government and the public-sidewalk lobby, it will never happen.

I was losing him. “Listen, I’ll pay you to stop!†I yelled. “What would you consider an appropriate price point for stopping? I’ll offer you a thirteenth of an ounce of gold and a gently worn ‘Bob Barr ‘08’ extra-large long-sleeved men’s T-shirt!â€

He turned. In his hand was a revolver that the Constitution said he had every right to own. He fired at me and missed. I pulled my own gun, put a quarter in it, and fired back. The bullet lodged in a U.S.P.S. mailbox less than a foot from his head. I shot the mailbox again, on purpose.

“All right, all right!†the man yelled, throwing down his weapon. “I give up, cop! I confess: I took the bitcoins.â€

“Why’d you do it?†I asked, as I slapped a pair of Oikos™ Greek Yogurt Presents Handcuffs® on the guy.

“Because I was afraid.â€

“Afraid?â€

“Afraid of an economic future free from the pernicious meddling of central bankers,†he said. “I’m a central banker.â€

I wanted to coldcock the guy. Years ago, a central banker killed my partner. Instead, I shook my head.

“Let this be a message to all your central-banker friends out on the street,†I said. “No matter how many bitcoins you steal, you’ll never take away the dream of an open society based on the principles of personal and economic freedom.â€

He nodded, because he knew I was right. Then he swiped his credit card to pay me for arresting him.

02 May 2017

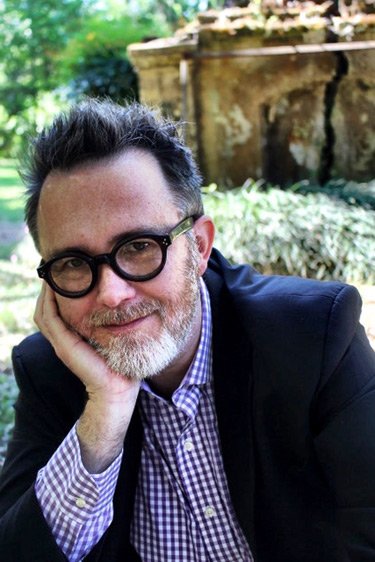

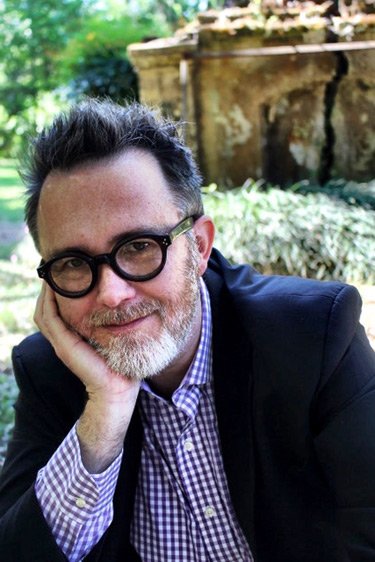

New Yorker profile photo of Rod Dreher by Maude Schuyler Clay.

Rod Dreher writes prolifically, at some times even well, and his recent book, The Benedict Option, which argues that the secular Left has won decisively, there is no hope for America or Western Civilization, and traditionalist Shventobazdies* like Dreher ought to emulate St. Benedict of Nursia and retreat from the world to private Christian communities resembling the monastery at Monte Cassino attracted enough attention on the part of the wicked, fallen world that he was profiled by the New Yorker.

*anglicized spelling of a sarcastic Lithuanian term for a person of publicly conspicuous piety, for someone sanctimonious, for a holier-than-thou, meaning literally “holy flatulator.”

Maude Schuyler Clay’s New Yorker photo (above) of Dreher makes him look like D.H. Lawrence Jr., like one of those mad British poets or writers (Henry Williamson or T.H. White, Gavin Maxwell or even T.E. Lawrence) who took to living somewhere deep in the English countryside in a thatched-roof cottage with a Goshawk or an otter. In her photo, Dreher looks like the suffering artist or visionary.

The photographer sent along to Dreher photo 2 (below), which prompted Dreher to write up another column, publishing both photos, and confessing that he thinks he really looks more like the latter.

And what a photograph the latter is. Dreher looks precisely like the very typos of the metrosexual hipster. As P.G. Wodehouse would probably observe: His knotted and combined knots part and each particular hair stands end on end like quills upon the fretful porpentine. And he is wearing glasses every bit as hideous as the glasses Marine Corps recruits are issued at Boot Camp, known universally as “Birth Control Glasses.”

Give that man a Pabst.

Hat tip to Maggie Gallagher.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'New Yorker' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|